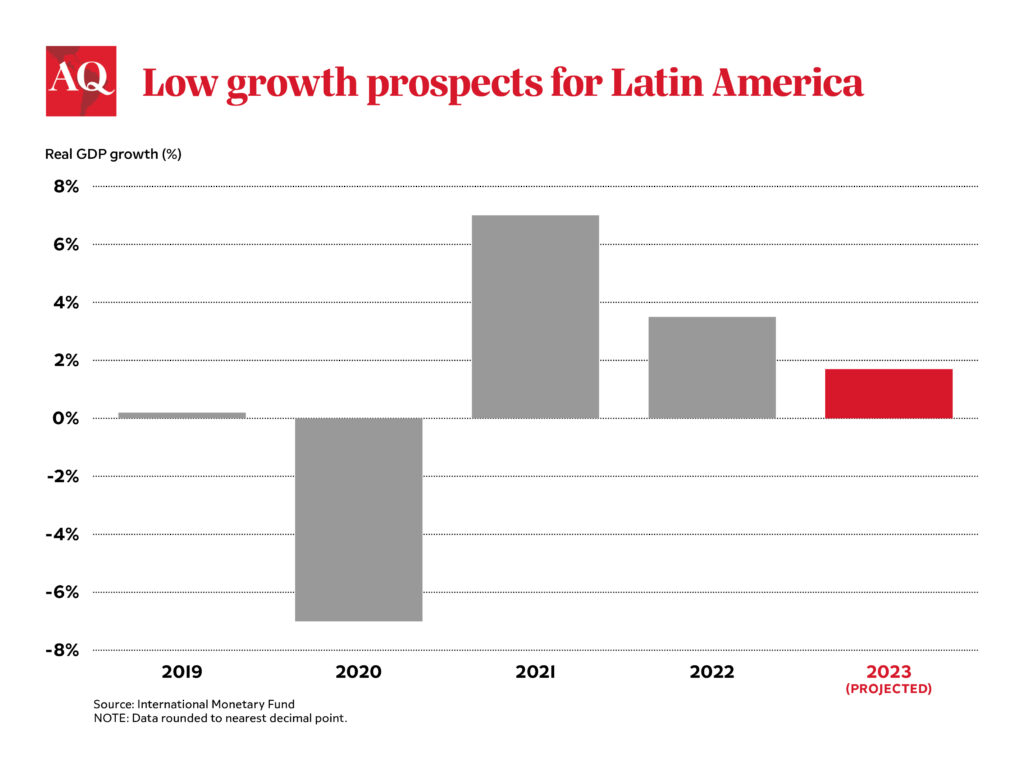

SÃO PAULO — Latin America’s political landscape in 2022 was dramatic. Colombia and Brazil presented nail-biting and course-altering elections, instability deepened in Peru, and democratic backsliding continued, particularly in Central America. Meanwhile, the region’s 2022 growth rate is expected to land at 3.5%—slightly above the global 3.2% average and only a modest recovery from the economic carnage of the pandemic.

Looking ahead to 2023, the region can expect continued instability.

First, the global macroeconomic and geopolitical environment is unlikely to improve much, which will impact the region deeply. Mediocre growth in Latin America—currently expected to fall to a meagre 1.7% in 2023, according to the IMF—is likely to keep public discontent high and the approval ratings of the region’s leaders low. This will increase the political costs of necessary fiscal adjustments, so most leaders will likely delay them or abandon them altogether to avoid the public’s wrath.

The political drama currently playing out is likely to continue. In Peru, President Dina Boluarte became the country’s fifth president in the last two years after Pedro Castillo attempted to dissolve Congress in an auto-coup. She now faces an uphill battle with Congress to avoid her own impeachment.

In El Salvador, the political alternatives to President Nayib Bukele are so unappealing that even as he erodes democracy in broad daylight, his approval ratings remain high. Tensions may also increase in Argentina, Paraguay and Guatemala as they prepare to hold elections amid major corruption allegations that have heightened the risk of political volatility.

As a consequence of this instability, a second trend will endure: strong anti-incumbent voter sentiment. It has already led to an astonishing string of 15 straight opposition victories in free and fair elections in Latin America over the past four years. This could lead to the election of a center-right or far-right president in Argentina in October next year. The second pink tide—which was even broader than the first as it now includes the region’s four largest economies—is likely to weaken quickly. Indeed, Argentina’s President Alberto Fernández’s chances of winning reelection seem so small he may not even run. In neighboring Paraguay, though, the leftist opposition has a rare fighting chance. Voters may oust the ruling Colorado Party on the back of corruption scandals involving longtime party leader Horacio Cartes, low presidential approval ratings and infighting within the government.

Meanwhile, Guatemala may prove the exception to rule. The government may interfere sufficiently—though less overtly than in Nicaragua or Venezuela—to ensure the continuation of conservative dominance after the elections in June. President Alejandro Giammattei’s administration has cracked down on independent journalism, civil society and the judiciary, suggesting the 2023 elections may not be free nor fair. The country’s ban on presidential reelection also helps candidates roughly aligned with the administration nonetheless portray themselves as meaningful alternatives.

A third trend in 2023 will be catalyzed by the election of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil. Latin America as a region will become a more prominent global actor—especially on debates about how to address climate change and deforestation. During the recent climate conference in Egypt, Lula signaled that he would seek to host the COP in 2025. Add to that the BRICS and the G20 summits in 2024, and it becomes clear that the Lula administration will dedicate significant effort to show the world that “Brazil is back.” Expect Brazil, and Latin America more generally, to loom large in the global debate on climate change as actors seeking to set the agenda.

Fourth, the democratic recession in Central America, above all Nicaragua and El Salvador, but now also Guatemala and possibly Honduras, is likely to continue unabated. Like El Salvador’s Bukele, Honduran President Xiomara Castro recently suspended a number of constitutional rights in the capital Tegucigalpa to combat criminal gangs. This slippery slope may lead to significant erosion of democratic rule and inspire copycats elsewhere. This is especially true given the very limited practical impact of regional rules as norms to protect democracy, such as the Inter-American Democratic Charter meant to help keep leaders in check. As a consequence, large-scale emigration from Central America is set to continue.

Finally, despite a temporary ideological alignment between governments in Latin America, meaningful regional initiatives to deepen integration will be very limited. Lula’s advisor and former foreign relations minister Celso Amorim raised the possibility of pursuing a monetary union with Argentina, an idea as ill-conceived and unrealistic as when it was aired by outgoing Finance Minister Paulo Guedes. Plans to relaunch UNASUR were also floated.

But bold initiatives will continue to be stopped in their tracks by domestic uncertainty, the declining importance of regional trade and profound disagreements between left- and right-wing governments about Latin America’s place in the world. The current impasse within Mercosur between Uruguay—keen to sign a trade deal with China and join the Pacific-centric CPTPP independently of the regional bloc—and Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay hints at what is to come. Limited space for regional cooperation will also limit progress on the region’s most vexing problem of all: the consolidation of President Nicolas Maduro’s reign in Venezuela, which will complete a decade in March.

Taken together, these trends amount to a year that will most likely look somewhat like 2022. It will be defined by sluggish growth, challenges to democracy and the instability that these create. But there will also be talk of greater cooperation, as well as renewed Latin American leadership on the global stage.