BUENOS AIRES — Javier Milei’s core idea, the one that has made him the apparent frontrunner to be elected Argentina’s next president, is dollarization: a plan to dissolve Argentina’s central bank, eliminate the peso and adopt the US dollar as legal tender, thus ostensibly eliminating the runaway inflation that has held the economy prisoner for years.

But is the idea viable?

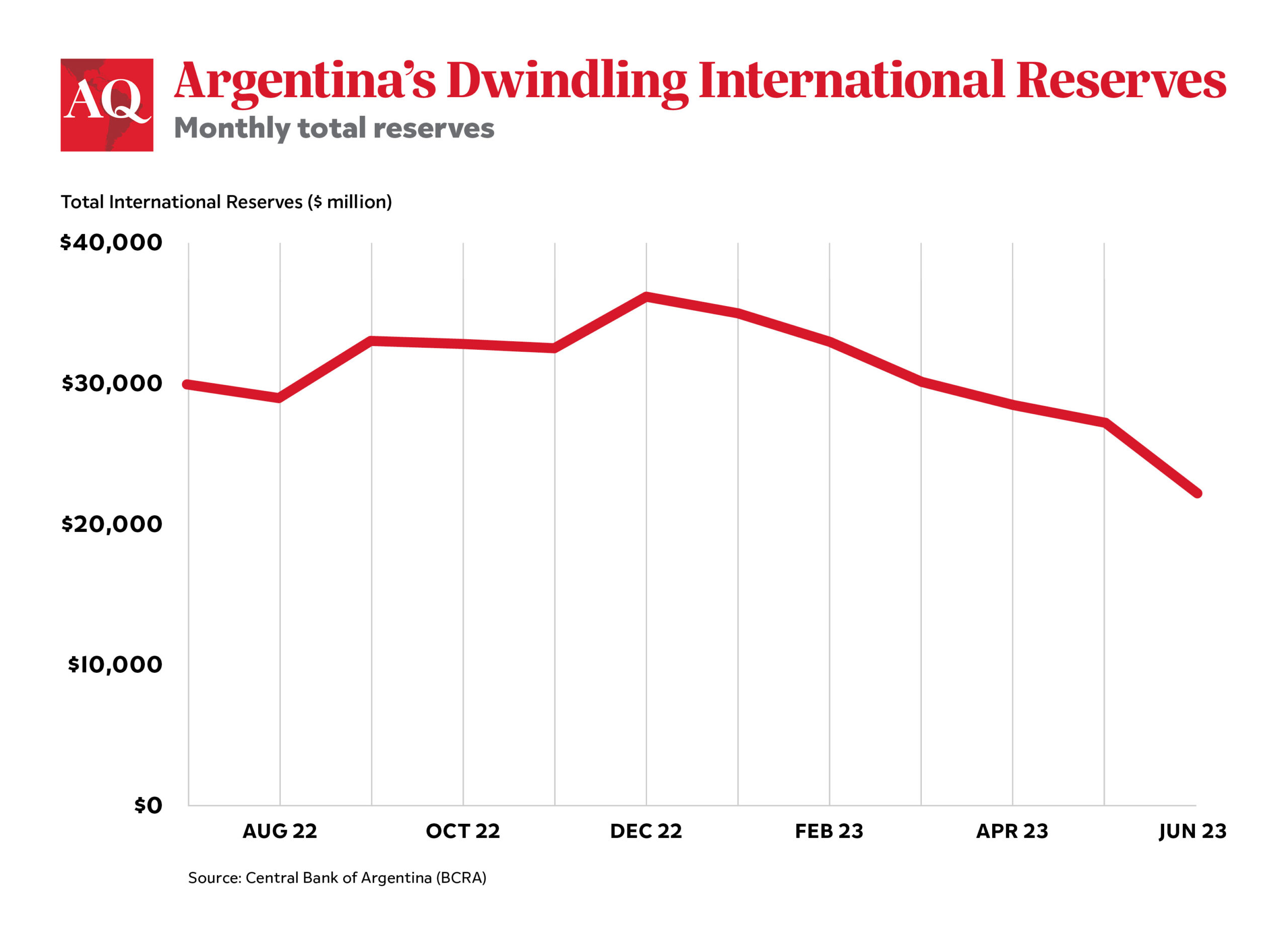

Independent analysts, economists and opposition figures consulted by AQ expressed doubts, noting the central bank has virtually no dollars in its coffers at present. A past attempt failed 24 years ago when President Carlos Menem’s plan for dollarization didn’t move forward as an economic crisis and a run on the peso caused the collapse of a currency board. Argentina already has trouble paying the International Monetary Fund (IMF) a $57 billion loan agreed on in 2018 and renegotiated in 2022, making a further aid package to support dollarization highly unlikely. And ultimately, they warn, dollarization will not by itself solve the core fiscal imbalances that have led Argentina to default on its debt nine times, including three in the past two decades.

“I think that (dollarization) is not feasible in the short term,” Alejandro Werner, former director of the Western Hemisphere Department of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), told AQ. “Argentina does not have the dollars to dollarize, and it does not have access to the financial market to obtain dollars. The only thing this would do is inject more Argentine securities into the hands of the international private sector, directly or indirectly, therefore further lowering the value of Argentine securities.”

Milei and his top aides strongly insist to the contrary. Emilio Ocampo, Milei’s economist in charge of the dollarization plan, says neither reserves in the central bank nor a multi-billion international loan would be needed to push the new system forward. In a radio interview in mid-August, he said that Argentines have over $200 billion in savings and other deposits overseas and elsewhere. “When that money enters circulation, for example, to pay taxes, the Treasury will automatically have currency available to move forward with the process,” Ocampo said.

According to Ocampo’s calculations, exchanging all the pesos in circulation and money in the banks at the current exchange rate would require about $60 billion, and some time for implementation. An individual who knows the markets well after a 20-year career on Wall Street, Ocampo highlights two stages: In the first, only $30 billion held by the public would be exchanged. The other half, currently invested in Leliqs, the central bank’s short-term bonds, would go to a second stage, which would take about four years.

“We calculate that in 16 months, all pesos will be exchanged for dollars. It will be a gradual process, as it happened in Ecuador, which took nine months,” he added. Bank deposits and loans would also be converted into foreign currency at the same time.

Last week, Milei said that converting pesos to the U.S. dollar will be done at the exchange rate determined by the market, currently at 730 pesos per dollar. The prediction met with widespread doubts. Sergio Massa, the economy minister and presidential candidate of Unión por la Patria, said the next day that dollarization would imply a 100% devaluation of the peso.

Speaking on a television show, Massa warned that Milei’s dollarization plan would mean that “public universities would no longer be free; train fares would cost 1,100 pesos and the bus fare would be 650 pesos.” Those fares are significantly higher than what Argentines currently pay. According to the Buenos Aires Herald, Argentina’s minimum fare is 25 pesos for trains and 52 pesos for buses in the Buenos Aires metropolitan area.

Marina Dal Poggetto, director of Buenos Aires-based Eco Go Consultores, concedes that dollarizing could help stabilize the economy due to its rigid anchor nature. But during a global crisis, dollarization could make it exceedingly challenging to absorb shocks. “The rigid anchor doesn’t allow you to adapt to flexible currencies when sudden stops occur and there are changes of monetary policies in the U.S., for example. Argentina blew up during Brazil’s crisis in 1999,” Dal Poggetto told AQ. She worries that dollarization’s entry costs will lead to a massive indebtedness to exchange the stock of the central bank’s bonds held by the country’s commercial banks.

The inflation conundrum

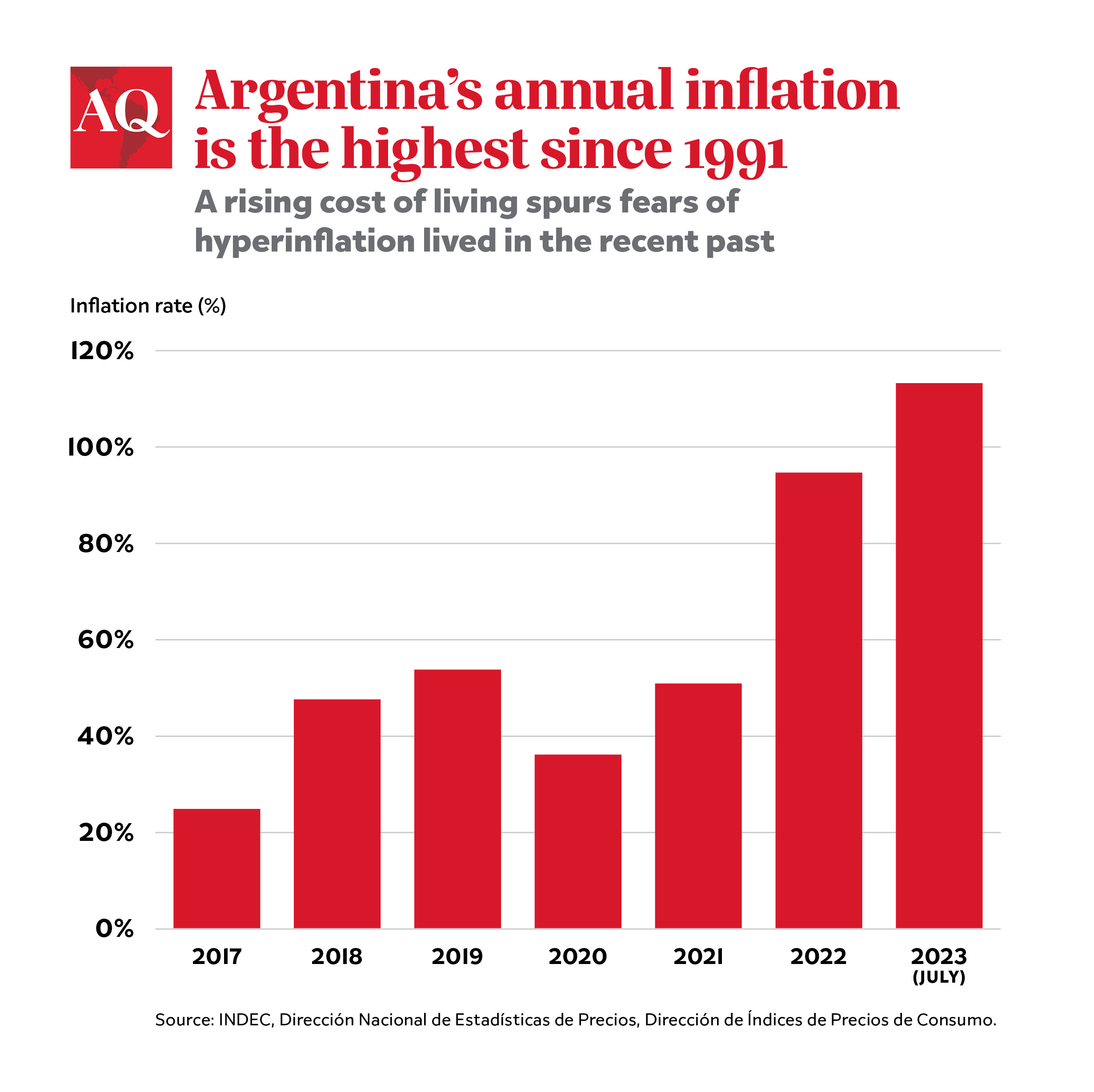

Experts agree Milei’s dollarization proposal has gained traction in Argentina because of the overwhelming demand for macroeconomic stability after over a decade of double-digit inflation and self-inflicted policy wounds. Argentina’s annual inflation cooled to 113.4% in July versus 115% in June. That was the highest level since 1991. According to some projections, the exchange rate is set to decline another 70% in the months ahead. Argentina’s presidential election will be held on October 22, and a possible runoff is scheduled for November 19.

Even if dollarizing the $632 billion economy could quickly help to reduce its inflation, it is a highly costly process, said Martin Castellano, head of Latin America research at the International Institute of Finance in Washington.

A dollarized economy will lack the flexibility to adjust to shocks, particularly in a more interconnected world economy featuring widespread floating exchange rates under inflation-targeting regimes. Also, the asymmetry with the U.S. economic cycle could lead to policy procyclicality, Castellano said. In contrast, the macroeconomic and policy imbalances it creates remain, given the option to avoid fiscal discipline by exhausting all possible financing sources, including asset sales and pension funds.

“The argument that the regime would force policymakers to make the economy more flexible through labor market and other reforms while becoming fiscally austere has simply not been corroborated,” Castellano argues. He added that dollarization has made countries vulnerable to external shocks and in a low growth path amid sustained real exchange rate overvaluation.

Defying expectations, Milei thinks the process will not be complicated. “Because inflation—everywhere and always—is a monetary phenomenon generated by an excess amount of money [in circulation]. We want to dollarize with the basic scheme, and we can do it. And is it easy? Super easy,” he told El País in July.

Regional inspiration

Argentina could find inspiration from Ecuador, Panama and El Salvador, three nations that have adopted dollarization with mixed results, but left behind a past of high inflation for a more stable monetary system. Those countries have had the region’s lowest inflation levels for the past 20 years. In contrast, according to data compiled by Trading Economics, Argentina’s inflation rate averaged 189.99% from 1944 until this year, reaching an all-time high of 20,262% in March of 1990.

Werner points out that Argentina’s instability arises from fiscal imbalances, and dollarization won’t fix those problems. “In the case of Argentina, it is a fallacy. Ecuador is dollarized and has very big fiscal problems, which is why it does not have access to financial markets. That’s why Ecuador’s bonds trade similarly to Argentina’s, like an economy in distress. So, thinking that by putting you in this straitjacket, society understands that you have to do the rest, I think it’s fallacious,” Werner argues. “From the economic point of view [of the] size, diversification and sophistication of Argentina, dollarization is clearly not an optimal exchange rate regime,” Werner added.

Echoing a similar skepticism, Mark Sobel, the U.S. Chair of the Official Monetary and Financial Institution Forum, OMFIF, wrote in an article published in August that the unorthodox policy “is not the answer” for Argentina. Dollarizing the economy is “a potentially perilous ‘no exit’ strategy. It could sow the seeds for a huge contraction and crash while deflecting attention from the tough work of fixing the economy,” he said on behalf of the London-based think tank focused on global policy and investment.

Regardless of who will take the presidential Casa Rosada next, there’s little doubt about the most pressing issue to fix. “We do not know if it is convertibility, if it is dollarization, if it is the adoption of another currency,” Gonzalo Tanoira, president of San Miguel, a fruit and vegetable company, said in a recent WhatsApp chat discussing Milei’s ideas. “There are many alternatives; the issue is to be able to debate which is the most seriously viable,” he added.

—

Gabin is a Buenos Aires-based journalist specializing in economics and finance. He’s worked at El Cronista and Infobae. He also collaborates with specialized magazines.