El Salvador voted on February 4 for president, vice president, and all 60 seats in the National Assembly. Bukele won with an overwhelming majority, and his Nuevas Ideas party is expected to win almost all the seats in the legislature.

A second set of elections will be held on March 3 to choose mayors and councils in all 44 of the country’s municipalities and all 20 of its Central American Parliament (Parlacen) seats.

AQ asked analysts to share their reaction.

Valeria Vásquez, senior analyst for Central America at Control Risks

Nayib Bukele’s victory marks a turning point for El Salvador’s politics and democracy. It cements a one-party state and will make it yet more difficult for the political opposition to regain influence and contest Bukele’s dominance going forward.

On the political front, a Nuevas Ideas-controlled National Assembly will pass just about any law proposed by the executive, including constitutional changes that further undermine the independence of the country’s fragile democratic institutions. The economic front, however, will be a challenge for Bukele. The economy is now a top concern for Salvadorans and is unlikely to improve quickly.

Rising inflation, along with high levels of poverty and unemployment, could pose a significant threat to his thus far unwavering popularity. If prices continue to rise and the government is unable to respond, Bukele’s five-year run of strong popularity may end in his second term. However, given the erosion of the political opposition and the country’s checks and balances, it will be difficult for any serious challenge to emerge.

Christine J. Wade, political science and international studies professor at Washington College

Bukele’s wide margin of victory was all but inevitable. In a matter of six years, El Salvador has devolved from a two-party dominant, multiparty system to a single party state. The concentration of power in the hands of Bukele and his party, Nuevas Ideas, in such a short period of time is perhaps one of the most dramatic examples of democratic backsliding under a democratically-elected leader in the region.

The once dominant political parties, the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) and the Nationalist Republican Alliance (Arena), barely won 10% of the combined presidential vote. The right-wing Arena appears to have virtually collapsed. Late changes to vote allocation rules, redistricting, withholding public campaign financing, and a host of other irregularities during the campaign made it virtually impossible for smaller parties to survive.

Since the 2021 elections, Bukele has used his legislative supermajority to consolidate control over public institutions, including the Constitutional Court that enabled his unconstitutional second, consecutive term. With no daylight remaining between Bukele and other institutions, the “Bukeleization” of Salvadoran politics seems complete.

His anti-gang policies and brash showmanship have made him an undeniably popular president both at home and abroad, as demonstrated by the apparently record-breaking turnout among the Salvadoran diaspora—from Boston to Los Angeles—on election day. More than 75,000 Salvadorans have been arrested under the 22-month old “state of exception,” the centerpiece of Bukele’s security policy.

But showmanship is no substitute for governance, and the second term will inevitably increase pressure on Bukele to address the state of the economy. With food insecurity on the rise and exports in decline, Bukele will have to have to address the country’s socioeconomic ailments with policies that prove more effective than his stalled Bitcoin initiative.

Orlando J. Pérez, political science professor, University of North Texas at Dallas

The election’s results defy the strong anti-incumbent trend that has swept across Latin America and bring El Salvador another step closer to becoming a one-party state.

Bukele achieved his victory largely on the back of a permanent “state of exception” that has reduced gang violence but has also incarcerated more than 1% of the population. These conditions led to militarized security, increased surveillance across the country, and violations of various fundamental civil and human rights, including due process, casting doubt on how many of those incarcerated are actually gang members.

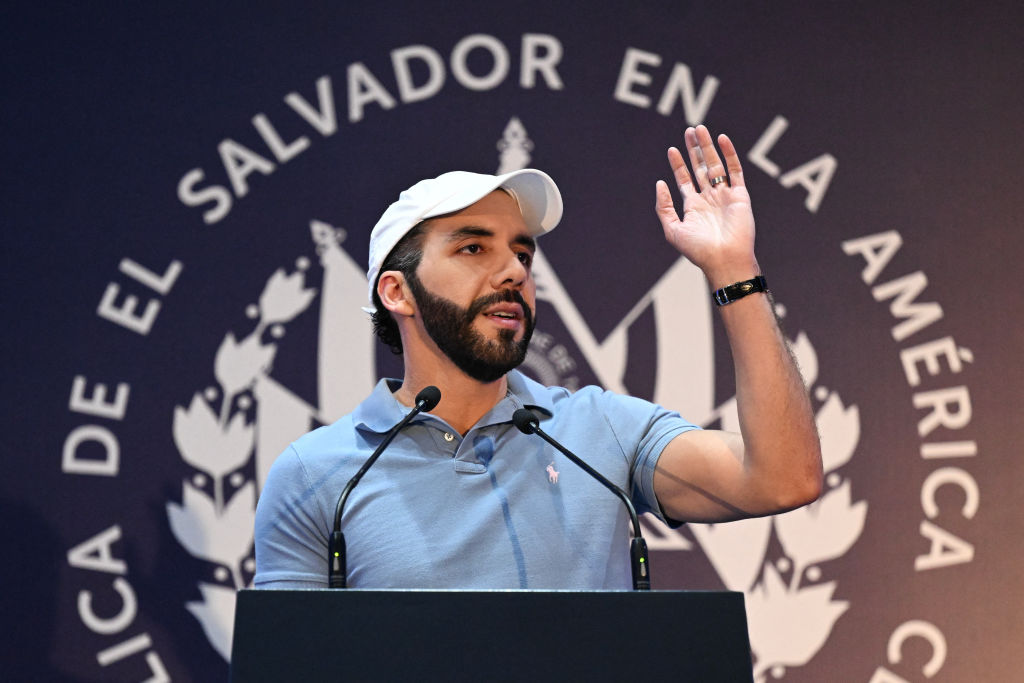

Meanwhile, the president, a former PR executive, has mastered the art of manipulating social media, and when manipulation wasn’t enough, he has passed laws that undermine the opposition. In a press conference before the polls closed, Bukele explained that El Salvador “never had a democracy,” emphasizing that now, “people decide.”

The Bukele “model” closely resembles Guillermo O’Donnell’s theory of “delegative democracy” or Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way’s “competitive authoritarianism,” in which elections provide leaders with license to undermine fundamental checks and balances. Many in Latin America have pointed to Bukele’s success as a model to follow. That success is rooted in El Salvador’s unique context and may not be replicable elsewhere, but its admiration will still seriously threaten liberal democracy in the region.

Boosted by this landslide victory, Bukele will likely double down on his security policies and rights violations. U.S. policymakers will find it increasingly difficult to engage with El Salvador on migration and other key issues if they also seek to prioritize democratic governance.

Brian Winter, editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly

Bukele’s landslide victory raises uncomfortable questions about democracy in El Salvador—and elsewhere in the world too, I think.

The debate here is whether a country has the *sovereign* *democratic* right to vote away its democracy. Or at least dilute it. In return for the trade-off—here, an extraordinary improvement in security, from Latin America’s most violent country to one of its safest.

I struggle to find parallels. Latin America’s true dictatorships, Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela all saw authoritarian creep without clear, fair elections to validate or endorse. Here, Salvadorans are saying, “Yes, this is what we want. We heard the world’s warnings about democracy and human rights, and we do not care.” Perhaps the election was not 100% fair, but this still seems like a mandate.

I think of other democracies that have suspended civil liberties in times of crisis. Examples in U.S. history include the Alien & Sedition Acts, the Patriot Act. Abraham Lincoln suspending habeas corpus and free press. World War Two internment camps. Many regretted these decisions afterward, but they occurred under democracy. I know the parallels aren’t perfect.

So today El Salvador has a newly elected leader with a strong, democratic (“popular”?) mandate to continue dismantling democracy and make himself ruler indefinitely, despite what his democracy’s rules say. Is El Salvador still a democracy?

For me there are two takeaways: The first is that few countries, and perhaps no country, is capable of resisting that rarest of things: the competent authoritarian. Because Bukele is clearly brilliant, capable, effective. He has skills other aspiring strongmen only dream of.

The other takeaway is that it will end badly, because one-man rule always does.