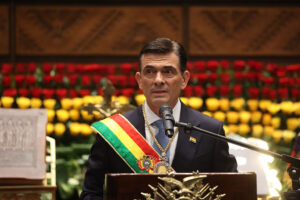

When Rodrigo Paz was sworn in as Bolivia’s president on November 8, 2025, few envied the task ahead. He inherited a nation under severe economic strain: inflation above 20%, foreign currency reserves nearly exhausted, public services fraying, and fuel lines stretching for blocks. Politically, he entered office without a congressional majority, with a restless population, and with enemies not only on the opposition benches but also within his own Cabinet.

Any one of these challenges might have immobilized a new administration. Yet in his first 90 days, Paz has done what many believed impossible: He not only survived the initial storm, but also began to change the nation’s trajectory.

As the son of former President Jaime Paz Zamora, Rodrigo Paz campaigned on a message of pragmatic change and national revival. But the economic peril of late 2025 left little room for gradualism. With the state hemorrhaging $10 million per day on fuel subsidies and unable to pay for basic imports, Paz moved quickly to implement a sweeping reform plan. On December 18, he issued Supreme Decree 5503—branded the “Decreto por la Patria”—declaring a national economic emergency and announcing the most significant policy pivot Bolivia had seen in decades.

At the heart of the decree was a dramatic, politically hazardous move: eliminating fuel subsidies. Gasoline and diesel prices more than doubled overnight, reversing a 20-year policy that had kept prices artificially low. The subsidies, while popular, had become fiscally unsustainable and encouraged rampant smuggling to neighboring countries. Ending them was necessary—but incendiary.

Paz understood the social costs this would entail and paired the decree with compensatory measures: a 20% increase in the minimum wage (to 3,300 bolivianos, or about $474), increases to school stipends and pensions, and the creation of a new emergency cash transfer program. He also unveiled pro-market reforms to attract investment, including streamlined regulatory approvals and tax incentives for repatriated capital. The message was clear: Bolivia was open for business while remaining mindful of its social contract.

An intense response

However, the public reaction was swift and furious. Within days, the Central Obrera Boliviana (COB), the country’s largest labor federation, declared a general strike and led nationwide blockades. La Paz, Cochabamba, and Santa Cruz were paralyzed. Roads were barricaded, supply chains were disrupted, and tempers were inflamed. For nearly a month, Bolivia teetered on the edge of chaos.

In that crucible, many expected the government to fold—as previous administrations had when confronted with gasolinazo protests. But Paz held firm on the most difficult issue: fuel subsidies. Despite relentless pressure, his government refused to reverse the price hikes. Instead, he opened negotiations with unions and social organizations, ultimately agreeing to repeal Decree 5503 and replace it with a revised and streamlined version—Decree 5516.

This new decree preserved the central economic pillar: market-based fuel pricing. It removed or revised provisions that had raised political and legal concerns, including the controversial fast-track for investment contracts that bypassed congressional oversight. By maintaining fiscal discipline while listening to public concerns, Paz struck a rare balance between resolve and responsiveness.

This outcome was an important political feat. Unlike previous leaders who retreated under pressure, Paz stood his ground where it mattered while conceding where compromise was wise. The COB, in turn, declared a partial victory—not by reinstating subsidies, but by ensuring that social protections remained, and future economic changes would proceed through democratic channels.

A fragile political landscape

Beyond the street protests, Paz also faced headwinds from within. His vice president, Edmand Lara, publicly broke with the administration just days into the term, criticizing the government’s direction and accusing it of betraying campaign promises. The spectacle of an open rift between the president and his second-in-command highlighted the fragility of Paz’s coalition. With no clear majority in the Legislative Assembly, every step forward has required negotiation and improvisation.

He has also had to govern in the shadow of former President Evo Morales, whose Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) remains a potent political force. While Morales himself has been absent from public view in recent weeks—leading to speculation that he has fled the country or is seriously ill—his allies have not hesitated to exploit the fuel crisis to stoke unrest. Paz’s break with the MAS legacy—both in style and substance—has been total. And nowhere has that been clearer than in foreign policy.

Paz has fundamentally reoriented Bolivia’s diplomatic stance. He restored relations with the United States and Israel, reopened dialogue with multilateral lenders, and even welcomed the return of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)—which had been expelled by Morales in 2008. This recalibration has already paid dividends: the Inter-American Development Bank and other institutions have signaled support for Paz’s economic program, offering new credit lines and technical assistance.

Of course, this pivot is not without political risk. The DEA’s reentry and tougher rhetoric on coca and cocaine production have alarmed segments of the rural population, particularly in the Chapare region. Morales’s supporters accuse Paz of selling out Bolivia’s sovereignty, and some union leaders warn that future concessions to Washington could reignite unrest. For now, however, Paz has made clear that he intends to prioritize institutional credibility.

His approach has surprised some. Though he comes from a social democratic lineage, Paz is governing more like a technocratic reformer than a party ideologue. His policies reflect recognition that economic stabilization requires difficult trade-offs—and that long-term sustainability depends on restoring investor confidence and rationalizing public spending. In an era when populist quick fixes often prevail, that kind of political courage is rare.

To be sure, the road ahead is long and fraught with risk. Inflation remains high, and unemployment is rising. As Paz’s term advances, the pressure to deliver tangible improvements in daily life will intensify. Paz will need to convert short-term stabilization into inclusive growth while navigating a fragmented Congress and a restless electorate.

Nevertheless, the early signs are encouraging. By holding the line on key reforms and showing a willingness to listen and adjust, Rodrigo Paz has earned the benefit of the doubt. His first 90 days were more than a baptism by fire—they were a test of character. For now, he is passing that test.