This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Lula and Latin America

In 1914, Theodore Roosevelt embarked on a dangerous journey into the heart of the Amazon rainforest, following the mysterious River of Doubt. Across the two-month-long trip, the former U.S. president injured his foot in the river, lost 60 pounds, and nearly died—surviving only thanks to the efforts of a five-foot-tall Brazilian man, who came from a poor and partly Indigenous background.

This was Cândido Rondon: two-star general, explorer, scientist, conservationist and anthropologist. Born in a small city in Brazil’s Mato Grosso state and orphaned at the age of two, Rondon managed to win a place at the military academy in Rio de Janeiro, where he soon stood out on account of his excellent grades.

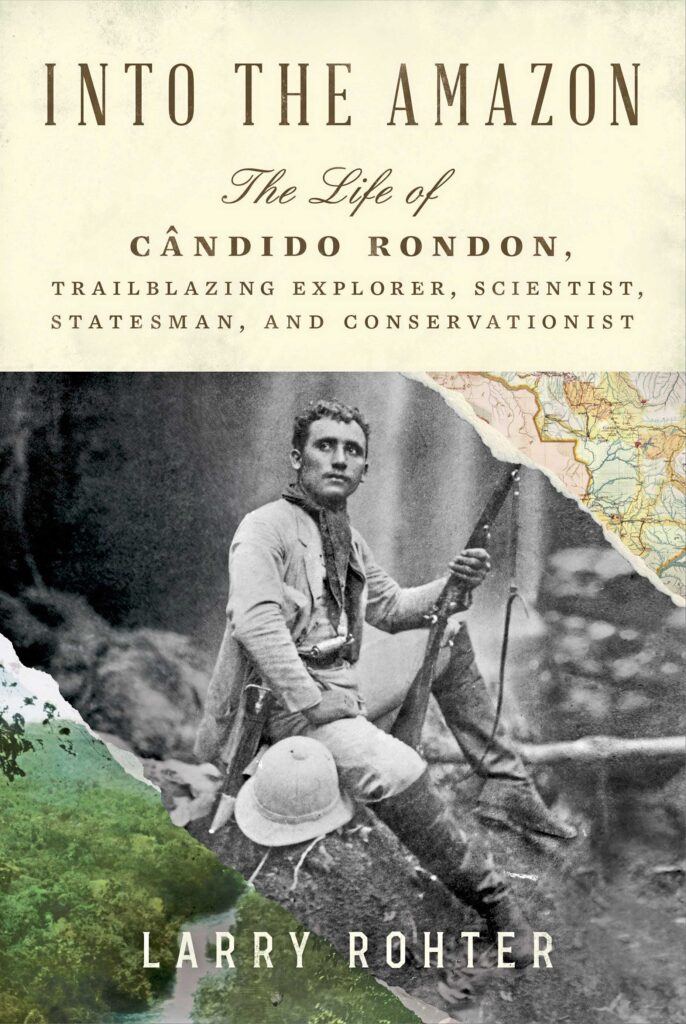

Rondon is also the subject of Into the Amazon, a new biography by journalist Larry Rohter, former Brazil correspondent for Newsweek and the New York Times. Following Rondon’s long public career—stretching from the end of the Brazilian monarchy, in 1889, to his death in 1958—Rohter’s account is highly complimentary, praising Rondon’s statesmanship and describing him as the “greatest tropical explorer in history.”

It’s true that today’s Brazil bears the stamp of Rondon’s considerable influence. As army engineer, Rondon laid 1,200 miles of telegraph wires through inhospitable terrain, discovered and cataloged unknown species and was the first to contact isolated Indigenous communities. Thanks to Rondon’s efforts, what was previously only known through cartographic projections and fantastic tales assumed real form. And in a country where Native peoples are often treated as an obstacle to development, this general was one of the first to advocate for their rights.

But despite Rohter’s meticulous research, which makes use of both U.S. and Brazilian archives as well as Rondon’s own diaries, his book has little to say about what Indigenous communities thought of his work—nor about Rondon’s own doubts, towards the end of his life, over whether leaving tribes in isolation might have been better than forcing a contact.

Still, it’s undeniable that Rondon laid the foundation for the protected Indigenous territories that now make up 14% of the country’s landmass and have become an established, if imperfect, barrier against deforestation, mining and criminal activity that affects Indigenous groups.

Into The Amazon: The Life of Cândido Rondon, Trailblazing Explorer, Scientist, Statesman, and Conservationist

By Larry Rohter

W.W. Norton

Hardcover

480 pages

To read Into the Amazon as a Brazilian is a strange exercise in seeing how the same problems regarding Indigenous people and the Amazon have endured through the generations, in some ways with few changes. Rondon’s ideas form a sharp contrast with the brutal realities Indigenous people have experienced since the outset of Portuguese colonization—including recently, under the Jair Bolsonaro government, which often turned a blind eye to illegal exploitation of Indigenous lands. In January, evidence of a crisis of malnutrition and disease among the Indigenous Yanomami caused widespread indignation and spurred an investigation, as photos of skeletal and sick Yanomami people circulated widely in Brazil and around the world.

Despite playing a bit part in the military coup that toppled Brazil’s monarchy and installed a republic, Rondon was, later on, a strong proponent of keeping the military out of politics. In his last interview, in the 1950s, he said, “The army should be the great mute”—another contrast with the present day, which has seen the resurgence of the military’s role in politics under Bolsonaro.

Upon taking office in January, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has sought to contain the damage in the Amazon, rushing support to starving Indigenous groups and creating the first Indigenous Peoples’ Ministry. But as the new minister of Indigenous peoples, Sônia Guajajara, recently said: “It won’t be easy to overcome 522 years [since colonization] in four.”

—

Audi is a reporter for The Brazilian Report