Correction appended below

On the night of March 2, 2016, three then-unknown assailants snuck into the private compound of Berta Cáceres, broke into her bedroom, and shot her three times at point blank range. The 44-year-old Honduran environmentalist died almost immediately.

If there was ever a death foretold, it was hers. Rumors of hit lists with Cáceres’ name on it had been circulating for years. Menacing text messages, unmarked cars, informants, phone taps: all formed regular parts of her daily routine. “We fear for our lives,” she told a foreign radio station more than a year before her murder. The volume of threats could fill an entire chapter of a book, a possibility on which Nina Lakhani’s Who Killed Berta Cáceres? duly delivers.

Lakhani picks up Cáceres’ story shortly after her assassins fled. With an admirable journalistic doggedness, she begins piecing together the whos, whats, wheres and, most importantly, the whys of Cáceres’ murder. A roving correspondent in Mexico and Central America for many years, Lakhani is well placed to get digging, following up endless leads and clocking up countless interviews.

Thanks to Cáceres’ high profile (she won the prestigious Goldman Environment Prize less than a year before her death), the basic details of the case are relatively well known. Co-founder of a Honduran human rights group, she rose to prominence as a passionate defender of indigenous rights. The case that catapulted her to fame was a proposed 22-megawatt hydro plant on the River Gualcarque. Thought to be financed by a mix of international banks and shady (yet well-connected) Hondurans, the multimillion-dollar Agua Zarca project had the government’s tacit backing. Local residents, most of whom were from the indigenous Lenca community, were less keen. Cáceres sided with the latter, a decision that would give rise to plenty of protests and column inches – but also her eventual death.

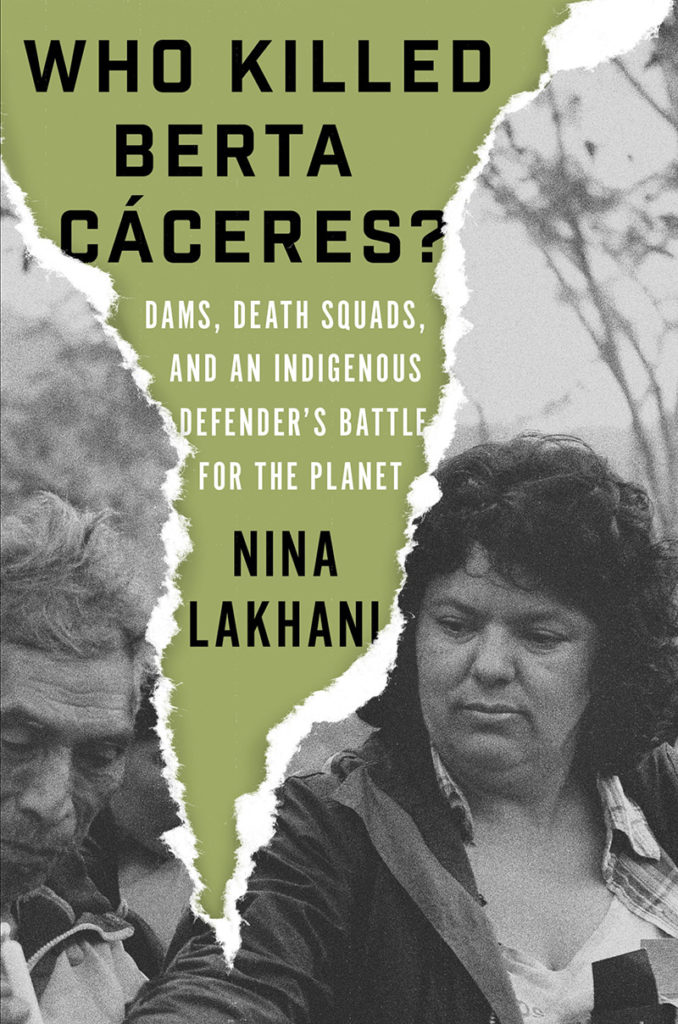

Who Killed Berta Cáceres?: Dams, Death Squads, and an Indigenous Defender’s Battle for the Planet

by Nina Lakhani

Verso

Hardcover, 336 pages

June 2, 2020

Behind the headline messages, far less is known about how her killing was conceived, planned and carried out. Here, Lakhani turns court reporter, mapping out every step of the botched police investigation and chaotic trial process in the book’s final third. It is proof of her determination and no doubt a welcome record for Cáceres’ supporters, but 100-or-so pages of legal process, court protocol, phone records, expert witnesses, and allegations met by counter-allegations will try all but the most committed reader.

For all the he said, she said particulars, however, the “who” of the book’s title introduces us to a truly odious cast of characters. Men (they are mostly men) like Jorge Ávila, an ex-police chief and head of security for the company behind the dam, who threatened Cáceres directly (“In a few days, you’ll be eating someone’s liver” were his exact words). Or David Castillo, the company’s privately-educated president, who uses charm rather than violence but was arguably the most devilish of the lot. Knowing all are real-life actors in a grisly true story gives the account an acutely chilling edge. It is not a screenwriter’s lazy pen that has the army major texting “tópala” (bump her off).

Yet, the ambition of Who Killed Berta Cáceres? is wider than the textual reconstruction of a landmark murder. It is as much about Cáceres’ life as her death, as much panegyric as postmortem. Lakhani appears to have met her subject just once, but succeeds in drawing her in full: as a precocious child enamored of her older brother (a pro-Sandinista, campesino-organizing Communist); as a guerilla fighter in El Salvador while still in her teens; as a human rights campaigner back on her native soil. Only as a mother (she is survived by four children) does Lakhani allow a negative note to creep in, pointing to her travel-related absences and her “disciplinarian” approach to child-rearing.

But it is Cáceres as a political thinker and activist where most ink is spent. This feels only right. Politics, and militancia in particular, ran in her blood. Her grandfather had been exiled during the dictatorship of General Tiburcio Carías Andino (1933– 49). Her mother, Doña Austra, a “no-nonsense matriarch,” was a Liberal Party politician (as well as a nurse and midwife). Cáceres lived and breathed politics. Not the politics of electoral parties and sharp suits (although she did once stand for vice-president). Hers was a more direct, more targeted politics; the politics of civic mobilization and grassroots action, of shoulder-to-shoulder solidarity and in-your-face protest. A politics of social movements, in short.

Lakhani credits Cáceres with two main political insights, both of which placed her in harm’s way. The first was an unswerving belief that “indigenous rights were human rights,” a conviction apparently inspired by the Zapatista uprising in Mexico in 1994. For Cáceres, the act of protecting lands, forests and rivers went hand-in-hand with safeguarding the inalienable rights of indigenous communities. Her second insight, as Lakhani tells it, was her capacity to link the local with the global. The everyday struggles in Lenca communities, Cáceres argued, began in New York boardrooms and on London trading floors. To be indigenista and anti-capitalista are two sides of the same coin, just as opposing a local dam and denouncing global finance are two sides of the same fight.

Yet the ambition of Who Killed Berta Cáceres? goes further still. True culpability falls not with the seven men who would eventually be prosecuted for Cáceres’ murder, Lakhani seeks to argue. To posit the blame on paid thugs is to miss the bigger picture: namely, that violence in Honduras is structural. By way of proof, the book provides a lengthy history of the country’s recent political economy, characterized by aggressive capitalist encroachment and the solidification of elite interests, all facilitated by the political, military and financial support of “Uncle Sam.”

The argument doesn’t entirely stack up, at least not in a legal sense. Despite two separate sub-chapters entitled “Follow the Money,” the precise powers at play here remain opaque. Her access to those allegedly pulling the strings is also (perhaps understandably) limited. Yet, as a cogent summary of contemporary Latin American leftist theory, the book soundly hits the mark. In the vein of Eduardo Galeano and his many acolytes, Honduras is painted as a Cold War/Washington Consensus throwback, where “transnational merchant elites” pull the strings and “gold-rush industries” ride roughshod over whatever – and whoever – stands in their path. Over the decades, the names may have changed, but the “neoliberal juggernaut” continues at pace.

Who Killed Berta Cáceres? will win its author no fans in Tegucigalpa’s country clubs or business schools, nor among the financiers of New York, where she now works as The Guardian’s first ever environmental justice reporter. As sure as night follows day, her political sympathies and her status as a foreign journalist will be used to discredit her and this book as biased, misinformed and self-serving. Indeed, the accusations have already begun, with her coverage of the Cáceres trial prompting defamatory press releases and barely disguised threats.

Will she care? I suspect not. First, because, within the terms it sets itself, this book represents an exceptional piece of reporting. Second, and more importantly, because witnessing the hostility released when truth is spoken to power will illuminate Cáceres’ own dark reality – and explain, more powerfully than any words, why this brave, principled mother-of-four was shot dead on her bedroom floor.

A previous version of this article mistook the date of Cáceres’ death

—

Balch is author of Viva South America! A Journey through a Changing Continent (Faber and Faber)