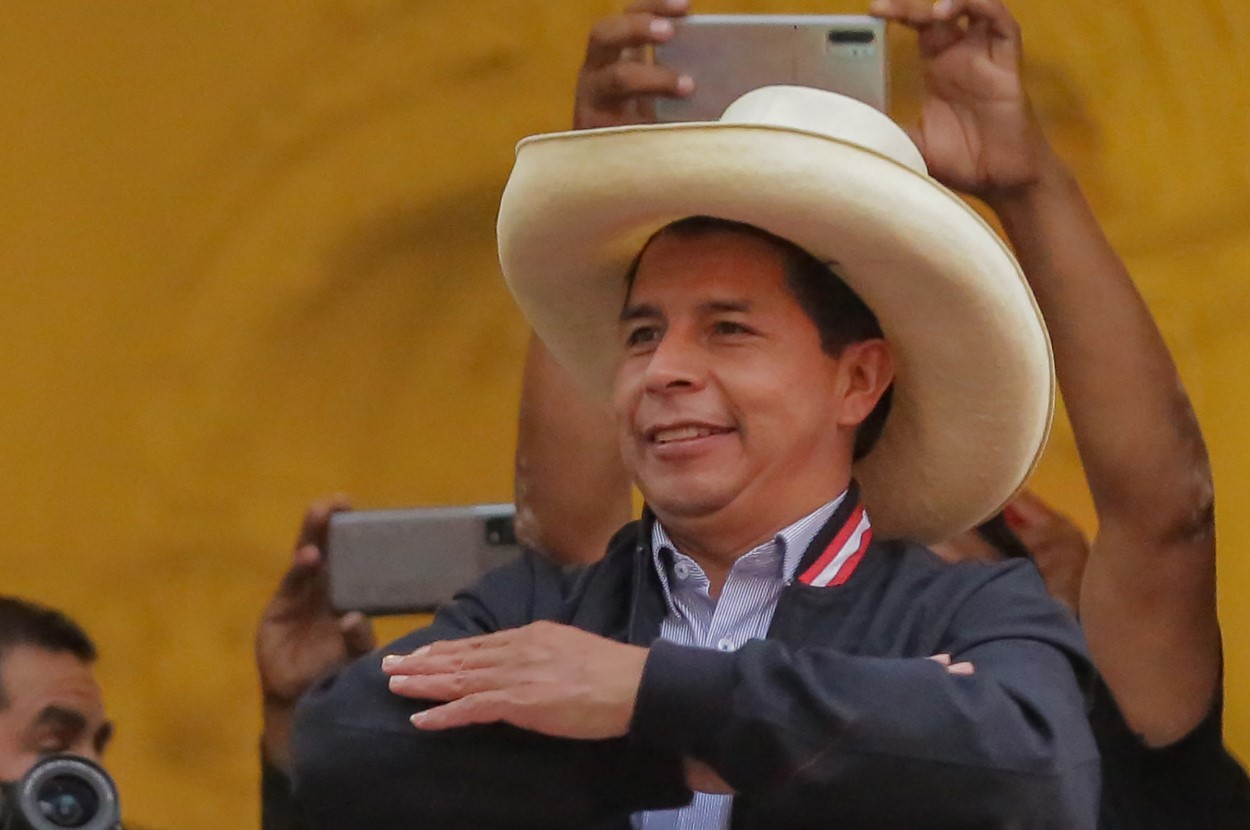

LIMA – Even though ballots are still being counted, it looks like Pedro Castillo, the schoolteacher and farmer who ran largely on a socialist platform, will be the next president of Peru. A virtually unknown candidate until surging unexpectedly to the lead on the first round of the election on April 11, Castillo’s economic proposals have caused alarm and uncertainty among Peru’s economic elites, who fear his presidency will be the end of the free market economic model that has been in place in Peru since the 1990s.

Castillo’s main promise is based on a simple message that he has repeated several times during the campaign: “No more poor people in a rich country.” Meaning, that Peru’s resources should benefit the population and not, as he says, the corporations and elites that have exploited and ignored everyday Peruvians. And the way to do this, according to his political party Perú Libre, which follows a Marxist ideology, is for the state to take control of industry and participate directly in the economy.

However, while this message may have resonated with many Peruvians and caused panic in others, it’s not clear that Castillo will be able to implement his policies in the manner in which he has promised. In fact, the most likely scenario for the country’s next five years can be summarized in one word: desgobierno. He will face high levels of opposition from a newly elected Congress which will be largely against him: Perú Libre won 37 out of 130 seats in the legislative, and there will only be one other leftist party, Juntos por el Perú, which only obtained five seats. The other eight parliamentary caucuses are all center-right or right wing, which will make most of his promises very difficult to uphold. For example, Castillo wants to call for a national referendum to approve the creation of a constitutional assembly that would then draft a new constitution. His focus on the constitution follows one main goal: to change its economic chapter. As it is currently written, the state can only carry out business when authorized by specific legislation and when it is in the national interest to do so. The objective, then, is to modify this chapter so that the government is able to, for example, nationalize the mining and energy sectors, or to unilaterally modify contracts with corporations so that they pay more taxes.

His main problem is that our current constitution does not include an article that regulates the implementation of a constitutional assembly, so the executive would first need to present a law to Congress to include this mechanism. This would need 87 congressional votes in two consecutive legislatures, numbers Castillo does not immediately have.

There’s also the threat of presidential impeachment. Ever since Martín Vizcarra was deposed from the presidency in 2020 on the grounds of “moral incapacity,” impeaching a president has become a viable option for many Peruvians. So much so that during the campaign, many voters unwilling to support Keiko Fujimori but still afraid of Castillo’s policies argued that it was better for him to be elected because he would be easier to remove from office. A line of reasoning that no doubt many elected parliamentarians already have in mind, considering that it only takes 52 votes in Congress to admit a motion to discuss the possibility of impeachment.

Of course, these scenarios assume that President Castillo will be respectful of the rule of law. But what if he decides to act unilaterally, perhaps dissolving Congress to get around the “problem” of the democratic process? Then too, he will face a lot of pushback, from an aggressive political opposition, an angry business sector, a hostile mainstream media, and most importantly, a military that has shown no sign of being willing to break with the constitutional order.

And then there’s Fujimori. On Wednesday, his opponent in the presidential race petitioned the electoral board to toss out more than 200,000 votes, which her team argues — with no credible evidence — are fraudulent. As it stands, it is hard to say if electoral officials will rule in her favor, but if not, she will still present a very aggressive and belligerent opposition to Castillo. (At time of publication on June 10, Peru’s Public Ministry had requested an arrest warrant for Fujimori for failing to abide by her plea agreement that allowed her to leave prison last year.)

The real test for a Castillo presidency will be if it can actually create a fairer economic reality and more political inclusion for everyday Peruvians. During the past four administrations, we heard again and again from the elites that Peru was one of the fastest growing economies, that its macroeconomic figures showed much fiscal discipline, and that the priority was to attract foreign investment to the country. All of this was true, but one key ingredient went missing: ensuring that economic growth actually improved the quality of life of the population. And nothing is more illustrative of the state’s failure to do so when we consider that the COVID-19 pandemic increased poverty in Peru by 10 percentage points in one year, between 2020 and 2021. It took us ten years to reduce poverty by that amount.

Over the last two decades, while many countries were shifting towards the left, Peru’s free market economy seemed impervious to change. Some cited our fear of leftist policies after the traumatic experiences of hyperinflation and the Shining Path in the 80s and 90s. Or perhaps, we were living in an oligarchy all along. The combination of a weakened civil society and labor groups after years of neoliberal policies, plus informal political parties, had allowed the economic elite to influence policy making without having to directly participate in politics; and it reduced the left’s ability to pose a challenge to the status quo. Until now.

Castillo’s election signals an end of an era in Peru, both dreaded and long awaited in equal measure. It stands to be seen what will result from this new period.