This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Uruguay

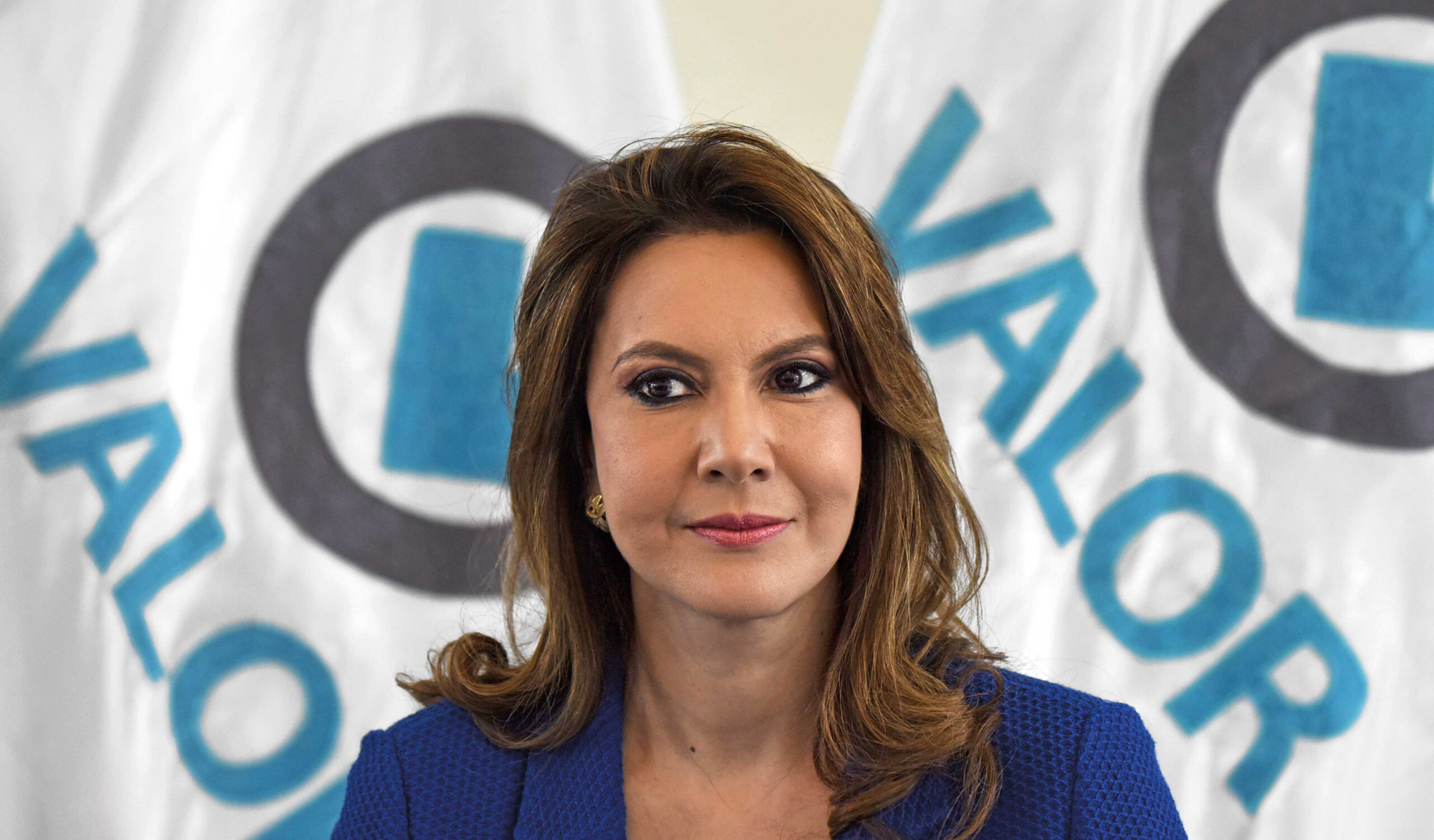

GUATEMALA CITY — Zury Ríos was already front-page news in 1990, at the age of just 22. That year, she led a dramatic protest in Congress in support of her father, Efraín Ríos Montt. He had been one of Guatemala’s most brutal dictators, and he was trying to run for president under democracy, even though the new constitution barred from seeking the presidency any leader who, like him, had seized power in a coup.

As the delegates who had written the constitution debated his fate, Zury Ríos, her mother and dozens of others disrupted the session for hours. The protesters hung a banner calling the delegates “dirty clowns,” threw ground chili powder into the eyes of one person who tried to take the sign down, and broke the eyeglasses of another, according to media accounts from the time.

Zury Ríos, now 55, has tried to cultivate a different, more democratic profile in the decades since. She was elected to Congress in 1995 alongside her father (the constitution carries no such ban on legislative office) and served four terms, pushing causes dear to their ultra-conservative party. At times, she also built broad alliances to champion progressive causes such as opposition to tobacco companies and protections for women and people with HIV.

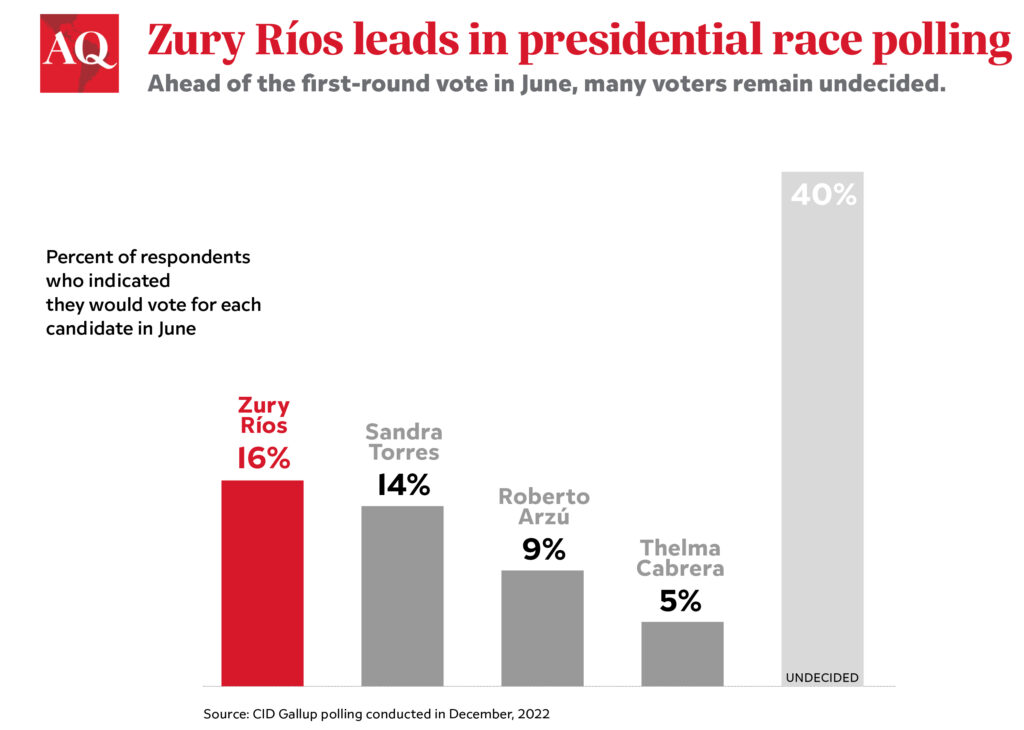

Today, Ríos is a favorite to win Guatemala’s 2023 presidential election, although she remains a divisive figure and, some say, a potential risk to democracy itself. Her candidacy may face legal challenges from her opponents, including current President Alejandro Giammattei. Although she has spoken of the importance of democratic checks and balances, Ríos’ persistent defense of her father’s legacy, and admiration for figures like El Salvador’s President Nayib Bukele, have raised questions about her commitment to Guatemala’s fragile institutions, which have already been badly weakened in recent years.

“She has the authoritarian tendencies of her father,” said Claudia Samayoa of Udefegua, a group that documents attacks on civil society. “She’s a smart woman and knows how government works.”

Efraín Ríos Montt was found guilty in 2013 of ordering acts of genocide during his 1982-83 presidency, one of the bloodiest periods of a 36-year internal armed conflict that left more than 200,000 Guatemalans dead, mostly at the hands of the military and state-backed paramilitary forces. Ríos Montt’s conviction was overturned prior to his death in 2018. “He taught me the values of believing in God, fighting for principles and being resilient,” Zury said the following year. “He was a role model.”

Zury Ríos declined requests for an interview through a spokesperson. But her defenders say she should not be punished or judged based on her father’s record, and she has earned plaudits from some beyond her conservative base for her legislative and other work. “Her agenda was to pass laws in favor of women and vulnerable LGBTQ groups,” said Nineth Montenegro, a left-wing former lawmaker who served with her in Congress. “She did it as a member of the legislative minority and she did it well, (with) the ability to build alliances with all parties.”

That kind of political savvy may allow Ríos to build a broader than usual political alliance in Guatemala, where right-wing figures have dominated the presidency since democracy returned in 1986. Ríos seems to have support from much of the country’s economic elite, and is beloved by the military old guard. She emphasizes her faith and is popular among Guatemala’s evangelical Christian community, who account for about 43% of the country’s population, despite her sometimes socially progressive work in Congress and her four divorces.

“She was a very capable member of Congress,” said Carmen María Solares, 41, a salon and spa owner in Guatemala City who plans to vote for Ríos. “I like that she supports the army and business owners, because that means prosperity.”

A shifting political landscape

These days, Ríos has made denouncing corruption a centerpiece of her messaging—with a special focus on the administration of President Giammattei, whose approval rating of about 24% makes him one of Latin America’s least popular leaders. And yet, her Valor Party was a reliable legislative ally of Giammattei’s until late 2022. The party finally broke with Giammattei in November over this year’s record budget.

This antagonism explains why Giammattei’s allies on Guatemala’s Constitutional Court may try to rule once again that Ríos’ candidacy is illegal—as the body did in 2019, arguing that the constitution bars close relatives of coup leaders from serving as president. Last year, Guatemala and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights reached an agreement on a case about individual political rights with Ríos at its center, which seemed to reverse that finding and clear the way for Ríos to run in 2023. But the consensus behind that decision remains delicate, and apparently subject to politics. A close advisor to Ríos said, “Her candidacy hangs from a very thin thread.”

The rivalry between Ríos and Giammattei reflects what many describe as Guatemala’s unique path toward authoritarianism. It has been not personalistic, but systemic; presidents have been limited to one term in office, so there has been no single figure in whom power has been concentrated along the lines of Bukele in El Salvador or Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua. Conservative presidents with much in common have come and gone, often fighting among themselves. Meanwhile, political power has resided largely in a web of alliances that dominates Congress and represents overlapping networks of elites, organized crime and other power brokers—what some in civil society call the “Pact of the Corrupt,” who all benefit from reduced transparency and accountability.

Apparently aware of the political class’s unpopularity, Ríos frequently portrays herself as an outsider and speaks about the importance of institutions and anti-corruption efforts. “We need to rescue the republic,” Ríos said at a November rally. “A republic needs checks and balances.” But she has also heaped praise on figures like El Salvador’s Bukele, who has dismantled checks and balances—including a constitutional ban on reelection. In its war on gangs, Bukele’s administration has declared repeated states of emergency and detained tens of thousands of people for alleged gang affiliation, often denying basic legal rights. In a campaign-style video last year, Ríos called Bukele’s “territorial control” policies “a model.”

Some see an appetite in Guatemala for a similarly strong leader. Economic growth has been relatively steady, but the country’s rates of inequality, poverty and malnutrition are among the highest in the hemisphere. Despite its negative social indicators, the public considers corruption the country’s most pressing problem, and Giammattei has been implicated in a series of scandals. He denies wrongdoing. Meanwhile, Attorney General Consuelo Porras—sanctioned by the U.S. for “significant corruption”—has stonewalled corruption investigations and pressed charges against anti-corruption judges and prosecutors.

A position of strength

Given the deterioration of checks and balances in Guatemala, some believe the next president could go even further than Giammattei. And Ríos is a far more experienced politician. Her rhetoric on security indicates that, like Bukele and President Xiomara Castro in Honduras, she may bet on aggressive security strategies to boost her traction with the public. In the July video praising Bukele, Ríos said, “A country can’t have development if it doesn’t have security. Between the guerrillas (of the armed conflict) and the gangs, Guatemala has seen so many of our brothers and sisters die.”

Her equating of gangs and guerrillas concerned many in Guatemalan civil society. Indeed, the conflict still looms large in today’s headlines. The Giammattei administration has chased numerous Guatemalan judges into exile, including Miguel Ángel Gálvez in November. He had been overseeing a case against former military and police officers for the disappearances of over 190 people from 1983-85. Conflicts between land-poor Maya communities and the plantations, dams and mines that dominate land ownership have also been on the rise.

The day the Constitutional Court barred Ríos from running in 2019, she was in Miami and appeared on Fernando del Rincón’s popular program on CNN en Español. In response to the Court’s decision, del Rincón asked her if she would call for violence. “You’re not going to set the country on fire? … Do you promise?” To Guatemalan viewers, this recalled the Black Thursday of 2003, when thousands of armed Ríos Montt supporters rioted in Guatemala City, setting fires and smashing windows, after the courts again blocked his candidacy for president. In the wake of the riots, the courts reversed their decision. He was allowed to run, finishing third.

To del Rincón, Ríos replied that she would not call for protests, and continued with a smile, “I promise. Everything. Anything you want.” Instead of fomenting unrest, she waited patiently, built strong alliances with other right-wing parties and waited until an international court recognized her political rights. Now she is ready to run, in a stronger position than ever.