This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on piracy in Latin America

As climate change opens up the Arctic, nations are trying to figure out how to divide its resources — while also keeping the peace.

They should look at what the region’s polar opposite did more than a half-century ago.

Following years of Cold War tensions and competing territorial claims, the landmark Antarctic Treaty was signed on December 1, 1959. Remarkably, it internationalized and demilitarized an entire continent, which became the first nuclear-weapon-free zone in the world. The treaty, in which Argentina and Chile played critical roles, also served as a precedent for agreements in other contested areas, such as the 1967 Outer Space Treaty and seven other zones free of atomic weapons.

How did this happen?

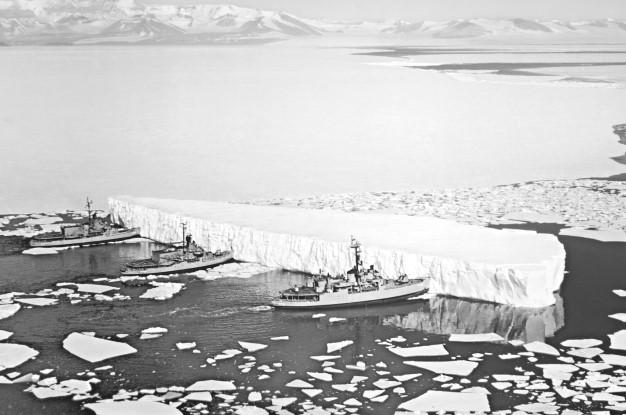

Unlike the floating ice in the Arctic, Antarctica is a continent, twice the size of Australia with an arm stretched toward South America. The Antarctic Peninsula is a mere 600 miles away from Patagonia and, on the other side, Oceania is some 5,000 miles away.

By the mid 1950s, seven nations had territorial claims in Antarctica. Australia, France, New Zealand, and Norway claimed different sectors of the continent, while Argentina, Chile, and Great Britain made overlapping assertions. Meanwhile, the United States and the Soviet Union remained keen, concerned observers.

In 1958, it appeared that Moscow might soon make a move. The International Geophysical Year (IGY), an 18-month venture in scientific collaboration among 67 nations, led to the spread of scientific bases across Antarctica. The USSR showed off its polar prowess when it set up several bases, including one at the magnetic south pole and another at the most difficult spot to reach on the continent, the so-called Pole of Inaccessibility. With the IGY set to expire at the end of the year, Washington worried that Moscow would carve out a menacing military presence in Antarctica.

The Dwight Eisenhower administration was divided over what to do. The military believed the U.S. should assert all territorial claims it might possess. By contrast, the State Department argued that asserting U.S. power in Antarctica would alienate allies and do little to deter Soviet advances.

State had the final word with a recommendation that Antarctica be demilitarized under an international agreement, preserving the continent for scientific exploration. The U.S. invited 11 other nations to the negotiating table: the seven with territorial claims, and four that had been active with the IGY (Belgium, Japan, South Africa, and the ussr). A year of informal talks led to what became known as the Washington Conference.

The Treaty Emerges

The conference occurred at an auspicious time of the Cold War. A brief thaw in East-West tensions had emerged during Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s visit to the U.S. in September 1959. Western delegations took notice of the “unusually affable” Soviet demeanor at the conference. By contrast, the British lamented the “very tiresome” and “prickly Latins.”

Argentina and Chile sparked debate. Wary of surrendering their claims, they sought an agreement that would last for only 10 years. After some wrangling, the delegations agreed that any treaty would initially last for 30 years, after which it would be up for renewal.

On Argentina’s initiative, the Washington Conference faced its greatest challenge of all: the issue of nuclear explosions. The parties had initially agreed that nuclear weapons and tests would be banned from Antarctica. But four days into the conference, Argentina shocked the other delegations with a proposal to ban all nuclear explosions due to the dangers of radioactive fallout. Specifically, the Argentine proposal would prohibit “peaceful nuclear explosions” (PNEs) for scientific exploration and industrial development.

Although Argentine Foreign Ministry officials claimed to be hamstrung by domestic public opinion, the U.S. suspected that diplomats aligned with the opposition were trying to use the issue to undermine Argentine President Arturo Frondizi. The president appeared to accept the PNEs idea, and the opposition thought this position could weaken his party in upcoming elections.

The U.S. objected to the Argentine proposal. It maintained that PNEs could one day help unleash Antarctica’s scientific potential. But the Argentine plan resonated with the other southern hemisphere delegations, with New Zealand adding a prohibition on the dispersal of radioactive waste.

The issue was the last to be resolved and threatened to derail the conference entirely. But ultimately, the U.S. capitulated and agreed to a full ban. Why? In part, the U.S. hoped to use the treaty to score a Cold War propaganda victory, keep Soviet missiles out of Antarctica and block communist China from gaining an unregulated foothold in the continent. As a result, Antarctica became the first nuclear-weapon-free zone in the world.

The Antarctic Treaty’s Challenges

The Antarctic Treaty did not constitute a cure-all for the continent. The agreement still allowed for the peaceful uses of nuclear power, and from 1962 to 1972 the U.S. operated a defective nuclear reactor at McMurdo Station that contaminated over 12 thousand tons of soil. After shuttering the reactor, the U.S. removed the contaminated soil to be buried north of Los Angeles.

The treaty also did not contain a strong environmental mandate. In 1991, its members created the so-called Madrid Protocol that banned mining and made all continental activities subject to an environmental assessment.

Today, the Antarctic Treaty faces as many challenges as ever. The rise of tourism (with a record 51,000 visitors last season) threatens the environment. So too could future competition for resources — Antarctica is home to the largest fresh water reserve in the world.

In 2048, the treaty and the protocol will be up for renewal, and many wonder if they will survive. China’s rapidly advancing presence, which in 2019 will include the completion of a $300 million state-of-the-art icebreaker and its first Antarctic airport, is raising eyebrows. And any amendment to the treaty requires unanimous consent, but full membership has risen to 29 nations.

Still, the Antarctic Treaty has been a success. Global powers prioritized diplomacy over military competition, while regional actors had an equal say. The treaty also captured the IGY’s spirit of scientific collaboration, an ethos that endures.

The contested sovereignties and militarization of the Arctic are greater than they have ever been in Antarctica. But the stewards of the high north would do well to look at the world’s southernmost continent and its 60 years of international cooperation.

—

Musto is a Ph.D. candidate in history at The George Washington University