Across the Americas, Internet usage is on the rise. Access to the Internet—fundamental to the full realization of human rights, according to the United Nations—can significantly improve quality of life by increasing knowledge and understanding, by broadening expression, and by deepening engagement with civil society.1 Especially since the widespread use of the Internet by activists during the Arab Spring movement, many have debated whether or not Internet use promotes democracy. But while the complex role the Internet plays in political change still remains to be studied, we can examine who connects regularly to the Internet in the Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region and whether Internet users hold values that are distinct from the values of those who are not connected.

Billions of people log on to the Internet on a regular basis, but rates of usage vary within and across countries. The biennial AmericasBarometer regional survey by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) conducts interviews in more than 20 countries in the region, and since 2008 has asked individuals how often they use the Internet. The data enables an assessment of the growth of Internet use, along with key barriers to access and differences in values held by those who are and those who are not connected in the region.

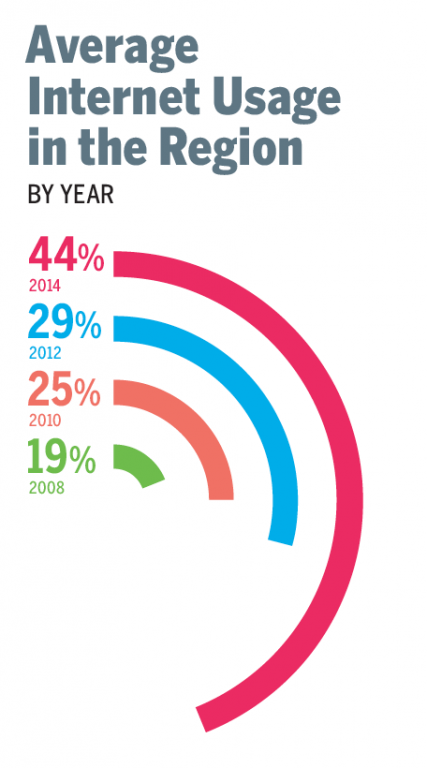

Since 2008, Internet usage has more than doubled in the Americas. The share of the population that reports regular Internet access (several times a week or more) increased from 19 percent in 2008 to 44 percent in 2014.2 This growth is in line with global trends in Internet connectivity, and with the increase—albeit not as dramatic—in household wealth across the region.3

If connecting to the Internet is critical to human rights, the impressive increase we see in usage is a positive sign for the region. But since deficits in connectivity remain, who is connected and who is not?

The Price of Connecting

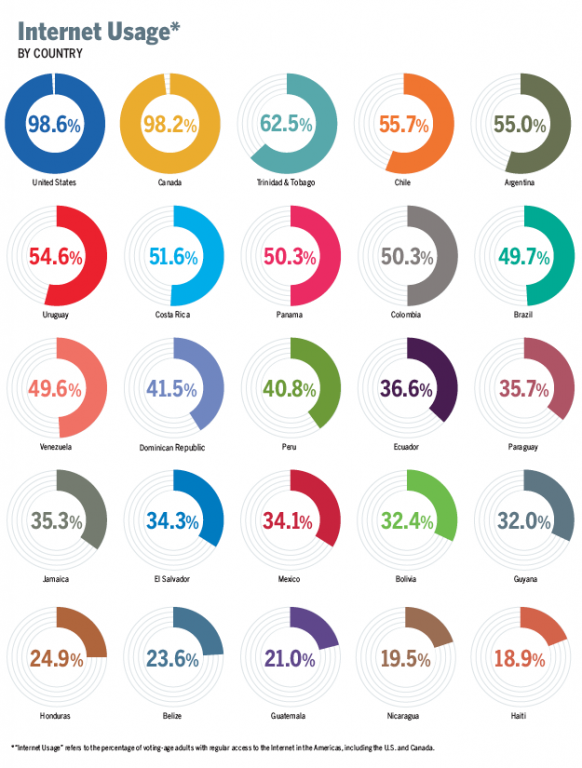

The link between Internet use and wealth is clear. A nation’s wealth (in GDP per capita) and the proportion of regular Internet users is highly correlated at almost a 1:1 ratio. The U.S. and Canada are by far the most connected (98.6 percent and 98.2 percent, respectively), and the wealthiest. At the other end of the spectrum, Haiti and Nicaragua are the least connected countries and also the poorest in the region. In both countries, less than 20 percent of the population reports using the Internet at least a few times a week.

An individual’s wealth, measured by an index of ownership of household items, also facilitates Internet access. On average, across the LAC region in 2014, only 13.5 percent of those who fall into the poorest quintile of wealth regularly use the Internet, while 69 percent of those in the wealthiest quintile do so.

The Demographic Divide

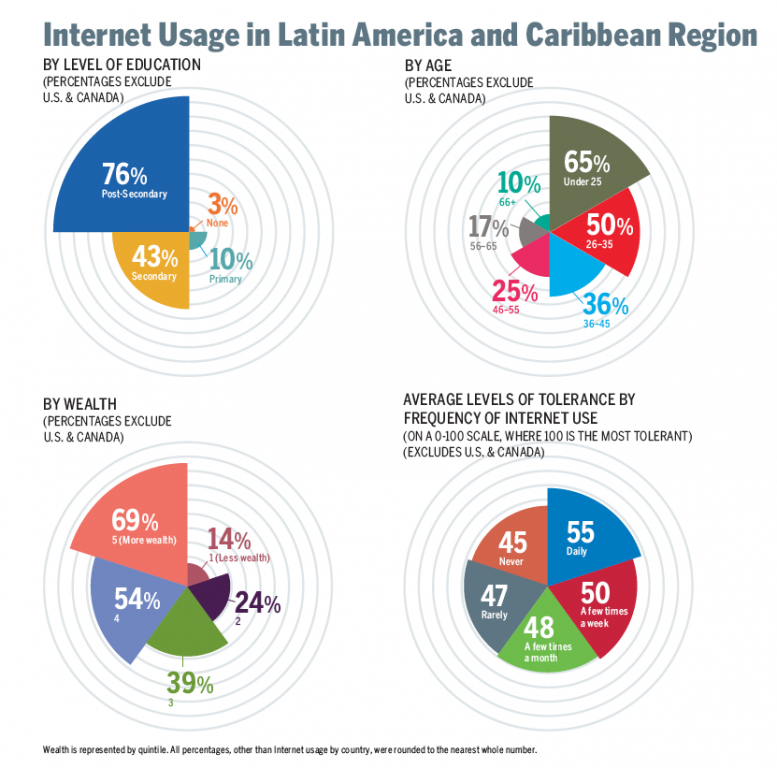

Education, urbanization, age, and gender are also predictors of connectivity. Only 3 percent of those with no education report regular Internet use. That percentage increases significantly with respondents’ level of education. Some 10 percent of those with only a primary school education report using the Internet several times a week or more; 43 percent of those with a secondary education report using the Internet at least a few times week; and 76 percent of those with a post-secondary education regularly use the Internet. Urban-rural divides also matter. The percent of urbanites who regularly use the Internet is 48 percent, while in rural areas, rates of regular connectivity drop to only 22 percent within the LAC region.

Not surprisingly, age influences usage. The youngest age cohort in the AmericasBarometer survey (those adults of voting age, but under 25 years) is over six times more likely to regularly connect to the Internet than the oldest age bracket (66 and older). There is less evidence of a substantial gender divide in the region, with 42 percent of men falling into the regular Internet user category, compared to 37 percent of women.

The Internet, Social Media and Democratic Values

A closer look at Internet and social media use shows a divergence in democratic values between those who connect regularly and those who do not. The AmericasBarometer survey measures political tolerance by calculating the extent to which individuals believe that regime dissidents (those who strongly critique the system of government in their country) should have basic rights to participate in politics. Past research has found that those in the region who use Facebook and other social media platforms for political communication express more support for democracy and higher levels of political tolerance than their otherwise similar counterparts who do not use social media in this way.4

The relationship between Internet use and political tolerance for those in the LAC region is similar to the relationship between social media use and political tolerance. Levels of political tolerance increase as Internet usage increases (from never to daily).

The connection between Internet use and the democracy-promoting value of political tolerance holds even when controlling for other individual characteristics (education, wealth, age, gender, and location). While there is no direct evidence that Internet use causes individual attitudes to change, the Internet is a forum for political engagement, and those who are connected tend to express higher levels of political tolerance.

Overall, increased rates of Internet use and comparatively high levels of tolerance among Internet users represent heartening news for those concerned with human rights and democracy in the Americas. But differences in education, wealth and place of residence remain important obstacles to realizing the Internet’s full potential for individuals to connect to information, resources—and with one another.