In less than a month, U.S. forces have carried out three lethal maritime strikes and one boarding in the Caribbean Sea targeting vessels allegedly tied to Venezuela’s Cartel de los Soles and its ally, the Tren de Aragua. The campaign marks the arrival of a new U.S. doctrine that may have a broad impact in Latin America: traffickers linked to designated terrorist organizations are no longer treated as criminals for prosecution, but as enemy combatants who can be neutralized without legal proceedings.

The scale of the deployment underscores how seriously Washington is treating this campaign. The naval and air assets concentrated in the Caribbean Sea today represent more firepower than the U.S. committed to the Battle of Midway in 1942—one of the pivotal clashes of the Pacific War—and it is the largest military mobilization since the deposition of Manuel Noriega in Panama in December 1989. The comparison illustrates the level of resources Washington is dedicating to confronting Venezuela’s state-protected cocaine networks, as the deployment of these forces represents a sizable multimillion-dollar daily expense.

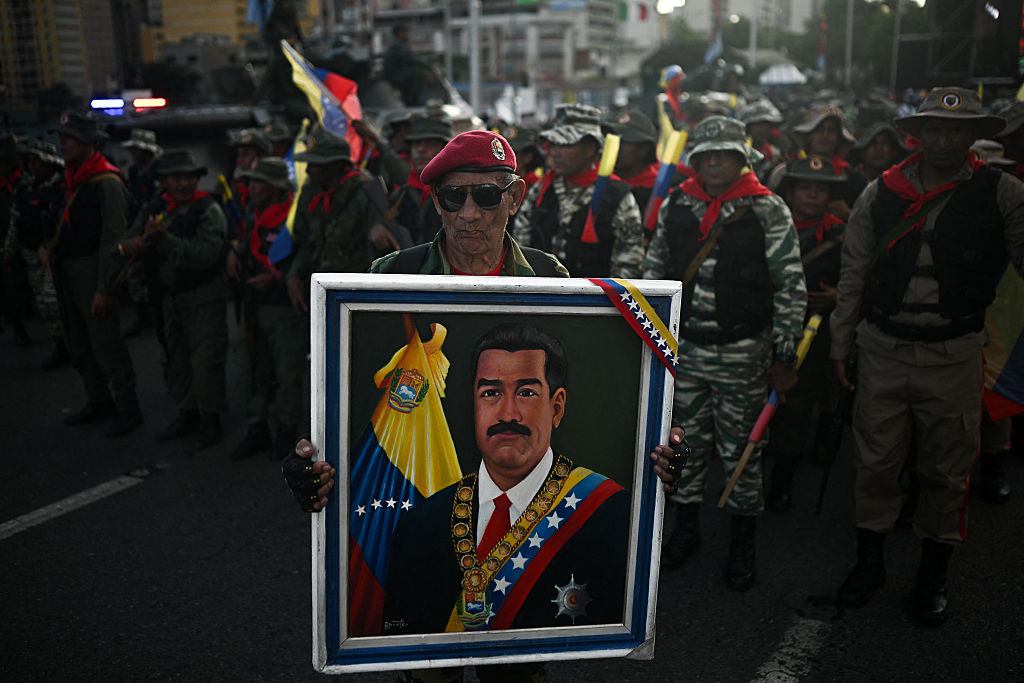

“We’ve recently begun using the supreme power of the United States military to destroy Venezuelan terrorists and trafficking networks led by Nicolás Maduro,” President Donald Trump said at the United Nations last week.

Understandably so, Maduro has seen the recent incidents as a threat to his illegitimate regime. Beating his chest to call for dialogue with Washington and urging the general population to defend the nation’s sovereignty, he even recently sent a letter to Trump requesting talks with Richard Grenell, the Special Presidential Envoy for Special Missions, who earlier this year had visited Caracas to negotiate a prisoner swap. So far, his rhetoric has not changed Washington’s stance, and Karoline Leavitt, the White House press secretary, said the missive was riddled with “lots of lies.” On Monday, Maduro signed a state of emergency decree after denouncing the U.S. “aggression” in a televised address.

Until now, the implications for Maduro and his inner circle are serious but do not suggest a traditional invasion. The strikes indicate that Washington is willing to bypass legal procedures and treat cartel-linked operatives as terrorist enemy combatants, undermining the protective shield that Venezuela’s armed forces have long provided. This raises the costs of maintaining illegal networks and diminishes the perception of impunity at sea, but it stops short of a ground intervention.

Rather than preparing for a full-scale invasion, the U.S. appears focused on sustained pressure combining targeted military actions, financial isolation through the SDGT designation, and diplomatic recognition of the opposition to weaken Maduro’s hold steadily. Nonetheless, President Trump may use any available authority that he considers necessary to prompt a behavior change, even if it involves scaling up military action in an effort to force Maduro out, as has been reported in some U.S. media.

Reaction and effect

The legal and financial framework behind this approach is just as important as the strikes themselves. In July, the U.S. Treasury designated the Cartel de los Soles as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist (SDGT) organization, adding the name to the list of several organized crime entities also designated on President Donald Trump’s first day in office. That step extended counterterrorism powers into the counternarcotics realm and imposed financial restrictions, cutting cartel-linked officers and networks off from the international banking system. By formally treating the cartel as a terrorist group, Washington limited external support for Nicolás Maduro’s regime and raised the costs for allies and facilitators abroad.

The designation also takes into consideration the cartel’s alliances beyond the hemisphere. U.S. and regional investigations have documented how Venezuela provides logistical space and financial cover for groups such as Hezbollah and Hamas. There’s also the issue of state protection. The Cartel de los Soles is not a loose criminal syndicate but a structure rooted in the Venezuelan armed forces. It generates billions of dollars in illicit rents, providing the Maduro regime with resources to bypass sanctions and maintain military loyalty. Cocaine trafficking has become a substitute for legitimate revenue in a bankrupt state.

The Trump administration is supporting its actions on Title 50 of the U.S. Code that governs covert action and intelligence operations, while the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force empowers the president to act against terrorist groups and associated forces.

Previous administrations used these powers to target al-Qaeda leaders in Yemen and Afghanistan. Under President Barack Obama, the same authorities were applied to lethal drone strikes that killed three U.S. citizens involved in al-Qaeda activities in Yemen in 2011, a precedent showing that citizenship did not shield operatives once they were deemed enemy combatants. Today, those same instruments are being applied to cartel operatives at sea.

The use of force and the hemisphere’s reactions

Most international observers saw Maduro’s 2024 re-election as lacking democratic legitimacy. Opposition candidate Edmundo González collected tally sheets suggesting he won by a wide margin, though the government-controlled electoral council refused to publish them. Last November, the U.S. formally recognized González as Venezuela’s “president-elect.” This context makes the U.S. campaign not only a counternarcotics operation but also a challenge to a regime already weakened by profound legitimacy concerns.

Reactions across the region have been mixed. Some governments warned that the strikes violated sovereignty and risked setting a precedent for intervention. Others, especially in the Caribbean Basin, quietly welcomed Washington’s willingness to confront Venezuela’s trafficking corridors; while this week, Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro called for a criminal investigation against Trump over the Caribbean attacks in which 17 people were killed. On the global stage, Russia and China are expected to use the incidents in information campaigns, portraying the U.S. as an aggressor in Latin America. Yet the SDGT designation equips Washington with powerful financial tools that complicate the ability of Venezuelan networks and their partners to access global finance.

This doctrine is likely to resonate across Latin America as the Trump administration gains more legal support, reshaping how Washington deals with cartels beyond Venezuela. In Mexico, groups like the Sinaloa cartel and CJNG could be treated as narco-terrorist organizations subject to direct action. In Colombia, dissident FARC and ELN factions already labeled as terrorists may be included in joint operations under this framework. Haiti’s violent mix of gangs and cartels could prompt similar responses, while Ecuador’s rising cartel violence and drug trafficking routes may also lead to U.S. intervention. The message is that cartels connected to terrorism will be addressed as hostile armed groups rather than just criminal organizations.

A narrow window, a U.S. strategy

If the recent strikes and the boarding were the opening shots of a new era, five priorities will determine whether this new U.S. doctrine succeeds. The Trump administration needs to institutionalize the merger of counternarcotics and counterterrorism authorities, ensuring the approach remains effective even with changes in administration. Second, rebuild supply-side intelligence by restoring coca monitoring and enhancing joint data analysis with Colombia, Brazil, and Ecuador. At the same time, the administration must intensify pressure on Venezuela by combining sanctions, diplomacy, and intelligence operations and coordinating maritime interdictions with land-based disruption, including eradication and rural development programs. Last but not least, elevate counternarcotics as a public health mission to strengthen domestic support for international engagement.

The U.S. can sink vessels and seize record tonnage, but tactical victories alone will not determine the outcome. The ultimate measure of success is not how many traffickers are eliminated or how many tons are interdicted. Three strikes and one boarding have opened a new chapter; the test now is whether Washington can turn bold actions into a lasting strategy.