In my recent conversations with Venezuelans and those involved in efforts to restore democracy in the country, it’s been hard to ignore a shift in tone. Instead of hopes for a sea change, cohabitation and resignation are the watchwords of the current debate.

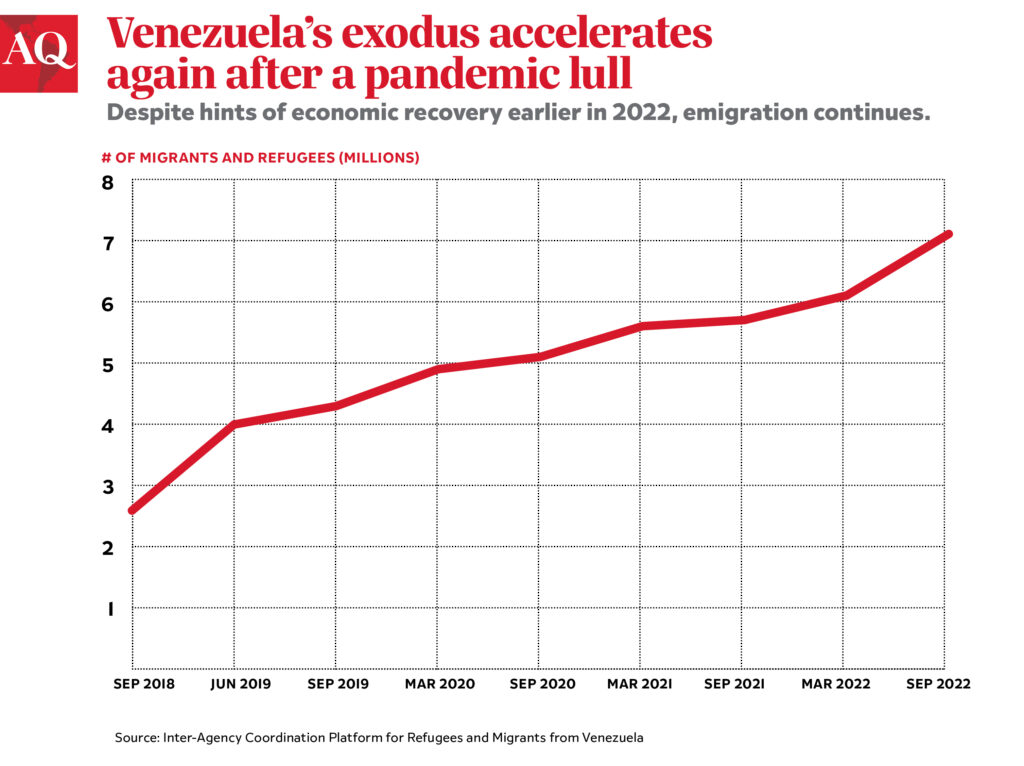

It’s not surprising that in the current context, interest in Venezuela’s push for democracy has taken a back seat to the country’s migration crisis, among the largest in the world. In the U.S. alone, more than 150,000 Venezuelans arrived at the United States southern border so far this year. Conversation has shifted from the root causes of the migration crisis to its most glaring consequences.

But even with diminished interest in Venezuelan democracy, the current landscape presents a unique opportunity to bolster its chances of a comeback—that is, if the international community, not just countries, but multilateral organizations, civil society and the private sector work to reengage.

Why now? For the first time in years, the international community and the Venezuelan opposition agree on the way forward: participation in the next constitutionally mandated presidential elections in 2023 or—more likely—in 2024.

A united opposition?

For years, the strategy among the Venezuelan opposition and international community centered on backing Juan Guaidó as interim president as part of an attempt to break the Maduro regime’s power structure. But over time, that strategy seemed to run its course, leaving behind a lack of consensus on how to move forward.

Today, there’s a consensus from all leaders in the opposition to participate in elections under Maduro—even from those who were historically the most reluctant, such as María Corina Machado and Leopoldo López’s Voluntad Popular party. Now they agree not only to participate—should conditions improve—but also on the need to hold primaries.

This shift came about for many reasons—not just the failure to deliver results of the previous strategy. Another reason to put hope in the electoral path came in the form of a significant opposition victory in last November’s regional election. Although the election was marred with irregularities, the opposition candidate, Sergio Garrido, won in Hugo Chávez’s home state of Barinas against the former president’s son-in-law and a former minister of foreign relations. Garrido’s victory showed the potential of a united opposition even in a in a stronghold of chavismo in the interior of the country, where opposition candidates have historically underperformed. The embrace of the vote as a tool for change also reflects the will of the people: Many who are reluctant to risk repercussions for protesting still want to have the chance to vote in genuinely competitive elections.

Much remains to be done regarding potential opposition primaries—for example, who will organize them, given that the country’s electoral authority is effectively under Maduro’s control? But if done in an inclusive and trustworthy manner, primaries could put an end to years of infighting between opposition leaders, not only generating a leader with a popular mandate but also serving to reconnect Venezuelans and would-be leaders to the political process. In fact, even the prospects of primaries have reconnected leaders with grassroots politics—for example, Juan Guaidó, who appears poised to run in opposition primaries for president at the next opportunity.

This change in strategy doesn’t mean the opposition is suddenly naïve on what to expect from elections organized by Maduro. Norway-led talks between Maduro’s government and the opposition, an effort supported by key international parties and which Maduro abandoned in September 2021, are set to resume this month in Mexico City. The opposition brings a concise set of requests to improve the electoral conditions: define the timing, reinstate the rights of banned politicians and political parties, update the Electoral Commission’s board with impartial experts and its voter registry with new voters and those abroad, and allow for qualified international observation. These do not begin to address the lack of press freedom and the country’s institutional wreck, but they provide a roadmap that limits Maduro’s dilatory tactics.

Here is the part where your skepticism should be kicking in. Why would Maduro, who has total control of the county, negotiate in good faith?

The answer is that he craves—even needs—international recognition and domestic legitimacy. For proof of the former, just look at how much his government has highlighted the recognition given by Colombian President Gustavo Petro. For the latter, look at the country’s delicate economic situation. Maduro’s government has no access to credit and the de facto dollarized economy is stuck with persistent high inflation. When he prints bolívares to cover his social costs, inflation shoots up because people immediately want to buy dollars. This has forced his government to declare that Christmas starts in October and start giving out holiday bonuses now to avoid a drastic exchange rate increase. Maduro needs sanctions relief to restructure the country’s private debt, a requirement for his investment attraction agenda.

However, it’s not just economics that could make Maduro accept electoral conditions. He also thinks he can win, under the circumstances. “His (polling) numbers are way above any opposition leader,” said Luis Vidal, the head of More Consulting, a Venezuelan polling firm.

Vidal added that Maduro could be incentivized to make concessions in order to gain sanctions relief, which in turn would give his government more income. Using his incumbent power, the state media apparatus and encouraging a third-party candidate run, there’s a path to victory for him, especially considering his track record of successfully employing “divide and conquer” methods against the opposition.

This is where the international community should come in. Progressive sanctions relief should accompany any political progress, but full-on recognition would take away Maduro’s key incentive to follow through in his commitments. If there’s progress that cannot easily be reversed, such as reinstituting the full political rights of banned political parties and their leaders, this should be followed by sanctions relief and progressive reestablishment of consular and diplomatic relationships. If the international community puts the cart before the horse, there will be no credible election.

No one is more aware of Maduro’s tyrannical nature than those who have directly opposed him. They are also aware that negotiation cannot be an end in itself. Active participation by the international community in this process would make it more likely to be productive. There is no better opportunity on the horizon to restore democracy in Venezuela than the upcoming presidential elections.