This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on COP30 | Leer en español | Ler em português

BELÉM, BRAZIL—The world is falling behind in its efforts to limit climate change. The chances of staying below the key thresholds of 1.5°C or even 2.0°C are slipping away. In fact, global greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015, increasing from 49 gigatons of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) to 53 gigatons in 2023. While the annual United Nations climate summits— known as the Conference of the Parties, or COP—have created important frameworks for action, they have not moved fast enough or broadly enough. Transitioning to a low-carbon economy has proven difficult due to high economic costs and political challenges.

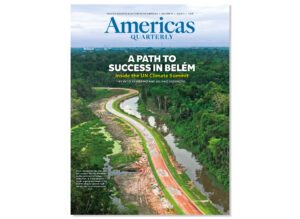

Against this backdrop, the upcoming COP30 meeting in November—taking place in Belém, in the heart of the Brazilian Amazon—could constitute a turning point. Brazil is uniquely positioned to help change how tropical forests are treated in global climate efforts: not merely as victims of deforestation and carbon emissions, but as vital assets in the fight against climate change. The Amazon, which accounts for half of the world’s tropical rainforests, plays a vital role in absorbing carbon dioxide, regulating weather patterns, and preserving global biodiversity. Its health is not just a regional concern; it is a global priority.

The urgency is clear. To reach an effective climate solution, two major actions are essential. First, the world must drastically reduce new emissions and stay on a path toward net-zero emissions by 2050. Unfortunately, emissions continue to rise. Second, even if emissions are brought near zero, we still must remove massive amounts of carbon that are already in the atmosphere.

With more than 40,000 participants from almost 200 countries expected to attend COP30 and related events in Belém, there will be no shortage of quality ideas. But there is one proposal poised to take full advantage of the event’s unique location as well as the support of the host government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. In short, Belém is a golden opportunity to increase the world’s focus on restoring tropical forests such as the Amazon—either by planting trees or allowing nature to regenerate.

Brazil is uniquely qualified to help change how tropical forests are treated; they are vital assets in the fight against climate change.

This proposal stands out as an immediate, cost-effective, and politically viable way to remove carbon from the atmosphere. Unlike expensive and unproven carbon-capture technologies, forest regeneration is affordable, scalable, and ready to deploy today. Focusing on forest restoration also brings other benefits: protecting biodiversity, conserving water, and supporting healthy ecosystem services. The Amazon forest alone holds a carbon stock comparable to the total historical emissions of the United States.

We need a new approach—one that recognizes the two-way relationship between forests and the climate. Tropical forests can absorb huge quantities of carbon if restored, and climate policies can help direct money and resources to protect and grow these forests. Instead of being sidelined, forests must become central to the climate solution.

Two priorities for forest action

To unlock the full climate potential of tropical forests, two areas must be tackled at the same time: halting deforestation and restoring degraded lands.

First, stopping deforestation is urgent. Despite some progress in agricultural productivity, tropical forest loss remains high. These ecosystems, often overlooked in existing forest finance mechanisms, are even more delicate than some observers think. If we don’t achieve near-zero deforestation by 2030, we risk losing one of the planet’s most important tools for absorbing carbon. Forests help stabilize the climate not only by sequestering carbon but also by regulating rainfall, preventing soil erosion, and supporting agriculture. Preserving forests also helps prevent the spread of zoonotic diseases, many of which originate in disturbed wildlife habitats. Their destruction accelerates biodiversity loss and makes it harder for local communities to sustain traditional ways of life. Thus, protecting high-integrity forests that currently face low deforestation pressure is critically important.

Second, forest restoration is a powerful way to remove carbon from the air. In Brazil alone, the excessive deforestation has left behind a vast area, equivalent to the size of Texas, of bare and badly utilized land. These lands offer a huge opportunity to restore forest cover, boost biodiversity, and bring back crucial ecosystem services. Despite financial and institutional barriers that have slowed progress, restoration can be achieved by planting native species, encouraging natural regrowth, and integrating reforestation with sustainable livelihoods for local populations.

A smart forest strategy must address both fronts: protection and restoration. The right balance will vary among tropical countries, depending on local conditions and institutions. That’s why any global forest strategy must be both adaptable and rooted in real-world contexts.

Brazil and other tropical countries have piloted policies to reduce deforestation, but political instability has often led those gains to be reversed over time. For forest-based solutions to succeed, they must be built to endure political changes. Creating resilient frameworks that are less dependent on the policies of any one administration will be key to long-term success.

That’s what makes COP30 so important. It is a chance to move from scattered pilot programs to a unified global framework that treats forests as essential infrastructure for climate stability. With the eyes of the world on Belém, there is an opportunity to send a clear signal that tropical forests are not just a concern for environmentalists, but a foundational element of global climate security and prosperity.

A new financial model for forests

To support this shift, we need a financial model designed for the scale of the opportunity and the complexity of the challenge. One promising idea involves a framework with two complementary payment systems: one to reward regions for growing new forests and removing carbon, and another to reward the protection of standing forests.

The first model relies on carbon offset mechanisms, whether through regulated carbon markets or other frameworks. In this framework, countries, high-emitting sectors, or large corporations are required to compensate for their greenhouse gas emissions as part of their transition toward carbon neutrality. Under this approach, these actors would purchase forest-based carbon offsets by paying tropical regions according to their net carbon balance—that is, the difference between the carbon absorbed through forest restoration and the carbon released via deforestation. Payments would go to regional funds that support a range of forest-related activities: enforcement, land ownership rights, Indigenous territories, and incentives for landowners who let forests regenerate. Such funding can also help resolve long-standing land conflicts and improve economic opportunities in remote areas.

In the Brazilian Amazon, where much deforestation is driven by low-yield cattle grazing, even modest payments for carbon could be transformative. This region could shift from being a major carbon emitter to a major carbon sink, removing as much as 18 gigatons of carbon over 30 years. Most of this would come from letting already-degraded land naturally regrow. Carbon payments create powerful incentives for farmers to shift from low-productivity cattle ranching to forest restoration, while also motivating governments to strengthen deforestation controls and promote ecosystem recovery in public lands. The potential is immense, especially when compared to costly engineered solutions that may take years to scale.

The second model, based on the proposed Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), would offer annual payments to countries for each hectare of preserved forest. The proposal suggests $4 per hectare per year, with steep penalties for any deforestation—a system that effectively pays countries to keep forests standing. Though not tied to carbon credits, the logic is simple: Reward stewardship and penalize forest loss. This approach treats forests like infrastructure, worthy of maintenance funding, just like roads or power grids.

Together, these mechanisms form a comprehensive strategy. One supports active carbon removal; the other secures long-term forest conservation. Implemented together, they could shift tropical forests from a peripheral concern to a cornerstone of global climate policy. Forests would no longer be merely a backdrop for climate action—they would become a primary stage.

Making it work

To succeed, this system needs major funding and global coordination. Current climate finance tools are not up to the task. One key step is setting a more unified global price on carbon. Right now, carbon markets are fragmented and inefficient. A shared price would allow countries to work together and bring down the overall cost of climate action. Coordinated pricing would also signal to investors and businesses that nature-based solutions are a reliable and essential part of the future economy.

Monitoring forest carbon accurately and affordably is also essential. Fortunately, satellite technology and data analysis now make this possible. A global system for verifying carbon changes would build confidence in results and improve transparency. Open, real-time data would empower civil society, local communities, and investors alike to track progress and hold institutions accountable.

It’s also important to keep the system simple. Instead of funding individual projects, payments would go to whole regions or countries based on outcomes—giving local governments the freedom to use funds according to their needs, while holding them accountable for results. This approach avoids red tape and honors national sovereignty. Countries would be rewarded for delivering measurable environmental benefits, regardless of the policy tools they choose to use.

Back to Belém

COP30 is more than another summit. It is a chance to reshape how we think about forests in climate strategy. The old view—that forests are merely victims or side players—no longer fits. Tropical forests can be central to solving the climate crisis. Their protection and restoration can also bring economic benefits, especially as rural economies evolve and digital tools connect even remote areas to global markets.

With the right support, carbon revenues can help build infrastructure and services in emerging cities, linking environmental protection to economic growth. Investment in nature can go hand-in-hand with social development. In fact, it must. The path forward is not about choosing between the environment and prosperity—it’s about designing solutions that secure both.

The path is clear. The question now is whether COP30 can deliver the action needed. The future of tropical forests—and of the global climate system—may depend on it.