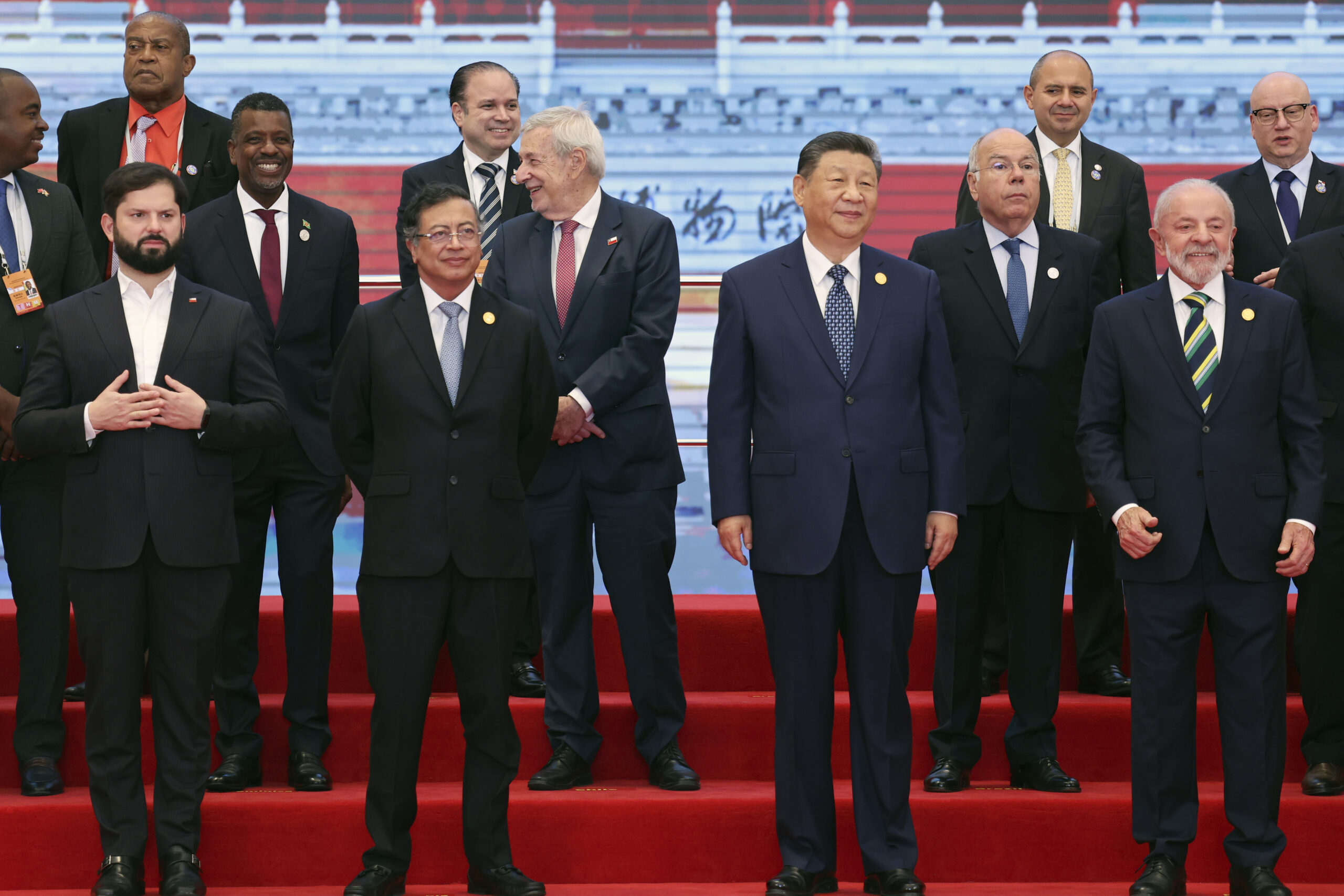

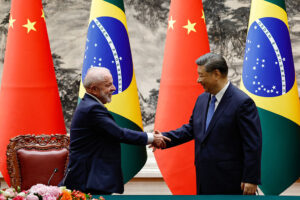

China is reshaping security cooperation in Latin America and the Caribbean under the banner of its Global Security Initiative (GSI). Launched by Xi Jinping in 2022, the GSI serves as Beijing’s framework for packaging its global security engagement. Unlike traditional defense partnerships centered on militaries and geopolitics, the strategy emphasizes policing, surveillance, and governance support, an effort to distinguish it from the United States’ security cooperation.

China is undertaking this effort in areas where Latin American governments frequently face urgent shortfalls, while consolidating the security-related activities China has pursued in the region over the past decade under a single, unified initiative.

Four key features of GIS stand out: a focus on law enforcement and domestic security over military engagement; engagement with local actors beyond central governments; a holistic security model that blurs boundaries across sectors; and an indifference to political models or values-based efforts, such as human rights and anti-corruption initiatives. The strategy raises a crucial question: what should the U.S. do to limit China’s expansion on this front?

Law enforcement ties

Since its inception, the GSI has emphasized engagement with law enforcement bodies in addition to national militaries. Two years ago, China’s ambassador to Panama distributed 6,000 tactical helmets to the Public Security Ministry. That same year, the National Aeronaval Service and National Border Service each received 1,000 helmets and 1,000 bulletproof vests, while the National Police were promised 4,000 sets. These equipment transfers, though modest in scale, represent tangible and visible commitments to public security. This is happening across the region.

U.S. security assistance, by contrast, prioritizes military-to-military engagement over law enforcement. In the law enforcement arena, the U.S. places greater emphasis on strengthening and professionalizing security institutions through training and technical support, primarily provided by the Department of State’s Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) and the Department of Justice. By contrast, most equipment transfers occur through private U.S. commercial channels and are driven largely by market forces rather than direct U.S. government initiative.

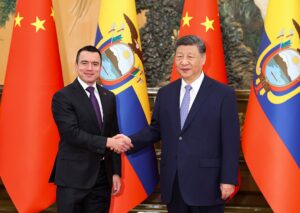

Beijing also promotes a “Safe City” surveillance model under the GSI. China has backed over 35 “Safe City” initiatives in Latin America, per Florida International University’s Security Research Hub dashboard. Argentina is home to the largest number of these initiatives, but they’re present across the region. In Ecuador, for example, the “ECU 911” emergency response system was financed through a $240 million Chinese loan in 2012. It comprises over 4,300 cameras and 16 response centers staffed by 3,000 personnel and was built out primarily by Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei and the state-owned China National Electronics Import & Export Corporation. Xi personally inaugurated a research lab at ECU 911 designed to experiment with large-scale facial recognition capabilities. Such systems, marketed as crime-prevention tools, threaten to violate civil liberties and create opportunities for Chinese intelligence collection.

The U.S. government has limited programs of this kind, and while some U.S. technology companies (e.g., facial recognition and surveillance systems) operate in the region, they remain largely uncompetitive in Latin American markets and function more as commercial enterprises than as deliberate extensions of U.S. foreign policy or security interests.

In some cases, the U.S. will leverage U.S. companies in their engagement in the region. For example, in 2024, Clearview AI was used in a U.S.-led operation aimed at combating online child exploitation. During a five-day operation in Ecuador in March 2024, authorities from 10 countries used Clearview’s technology to identify child predators and, within just three days, identified 29 offenders and 110 victims by processing 2,198 images. Clearview AI now operates in Brazil, Colombia, Chile, the Dominican Republic, and Trinidad and Tobago.

In addition to promoting “safe cities” and proliferating law-enforcement equipment, China is building an on-the-ground security footprint across the region to advance its interests. It established “overseas police stations” in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Cuba, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Panama, officially described as service centers for Chinese nationals abroad. In practice, however, they monitor diaspora communities, pressure dissidents to return, and extend China’s domestic security policies overseas. These stations complement Beijing’s broader efforts to co-opt elites and interest groups by blending civil, political, and security functions to manage the diaspora. They reflect Xi Jinping’s vision of the “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” by projecting influence abroad and asserting control over Chinese communities, serving as an operational arm of this strategy. Beyond these police stations, Chinese private security companies are also expanding their presence in the region. In Peru, for instance, China Security Technology Group signed an MOU with Grand Tai Peru to provide security in the mining sector.

Beyond central governments

China is also differentiating itself from the U.S. by working directly with subnational partners in provinces, municipalities, and even individual police departments, to sidestep central oversight and exploit rifts between local and national governments. Further, provincial and local law enforcement bodies are often resource-constrained and welcome technical support from China. This kind of engagement also offers China greater geographic access to sell its technologies. In 2012, Vice Chairmen of China Satellite Launch and Tracking General (CLTC) signed the initial agreement of a space facility in Neuquen, Argentina. Furthermore, China began construction at Neuquen before receiving formal approval at the national level. Satellite imagery from January 2024 verified construction three months prior to the site receiving formal approvals.

In another example, Argentina’s provincial government of Tierra del Fuego signed an MOU with China’s Shaanxi Chemical Industry Group to develop a $1.25 billion multipurpose port, power plant, and chemical production facility. The agreement was signed in August 2022, ratified in December 2022, and made public in June 2023. Once disclosed, it faced immediate opposition from local leaders and Argentina’s central government. The project also drew strong U.S. objections, as Chinese investment in Tierra del Fuego was seen as undermining U.S. national interests by providing Beijing with greater proximity to Antarctica. U.S. Southern Command leadership lobbied Argentina’s central government to pressure the provincial authorities to abandon the deal.

This case highlights China’s strategy of engaging directly at the local level, often bypassing central governments altogether. By contrast, the U.S. typically works through central governments to access local-level opportunities, emphasizing respect for national sovereignty.

Blurred security lines without strings

The GSI reflects China’s “integrated security” model, which deliberately blurs the boundaries between the military, police, intelligence services, diplomats, and the public and private sectors. By contrast, the U.S tends to maintain clear distinctions among these areas and maintain separation between public- and private-sector activities. U.S. compartmentalization, however, can at times limit opportunities to optimize programming.

Perhaps the most distinctive feature of China’s model is its indifference to regime type, corruption, or human rights. Whereas Washington often conditions cooperation on governance or rights standards, Beijing provides tools without political judgment. In the U.S. case, this frequently takes the form of tying aid to improvements in human rights. A clear example is the Mérida Initiative, a counterdrug and rule-of-law assistance program with Mexico. At the request of then-President Felipe Calderón, Washington provided support to combat drug cartels. Between FY2008 and FY2010, Congress allocated $1.5 billion to strengthen Mexico’s military and police forces. However, it also required the State Department to withhold 15% of certain funds unless its annual reports verified progress on human rights benchmarks.

By contrast, China’s detachment from these requirements was evident even before the GSI’s launch. In 2017, Chinese state-owned firms supplied Venezuela with anti-protest equipment used to repress demonstrations against Nicolas Maduro’s regime as the U.S. was implementing its “maximum pressure” policy. Around the same time, Chinese telecommunications giant ZTE helped develop Venezuela’s “Fatherland Card,” a national ID system that stores extensive personal data and has been used to monitor social, political, and economic behavior. Despite these authoritarian uses, Venezuelans were required to obtain the card to access social services—a practice that continues today. Under the GSI, such engagements are framed as part of comprehensive national defense cooperation.

U.S.-China competition

Beijing is not actively seeking head-to-head competition with Washington in Latin America’s security arena. Instead, it is exploiting gaps where U.S. engagement is limited or inflexible. While China’s initiatives often appear pragmatic and low-profile, they serve a broader purpose: positioning its model as an alternative to that of the U.S. Over time, this approach expands China’s security footprint while gradually eroding U.S. influence by offering cooperation that appears more immediate, responsive, and tailored to local needs.

To stay competitive, U.S. policy should become more agile, timely, and better coordinated across agencies, providing sustained support that is as strong as traditional military-to-military cooperation. U.S. should maintain a threat-focused approach, ensuring that cooperation addresses the security priorities of partner nations while promoting U.S. interests.

At the same time, Washington must continue to uphold its core values, including democratic governance, human rights, and anti-corruption efforts, while acknowledging that if it pulls back, others, especially China, will quickly step in to fill the gap. This could have serious long-term strategic consequences for the U.S. in its own hemisphere.