This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on A (Relatively) Bullish Case for Latin America

BRASÍLIA — For years, Erika Hilton struggled to survive on the streets of São Paulo. Now, as a lawmaker, she’s trying to change the legislation and culture that made her an outcast in the first place.

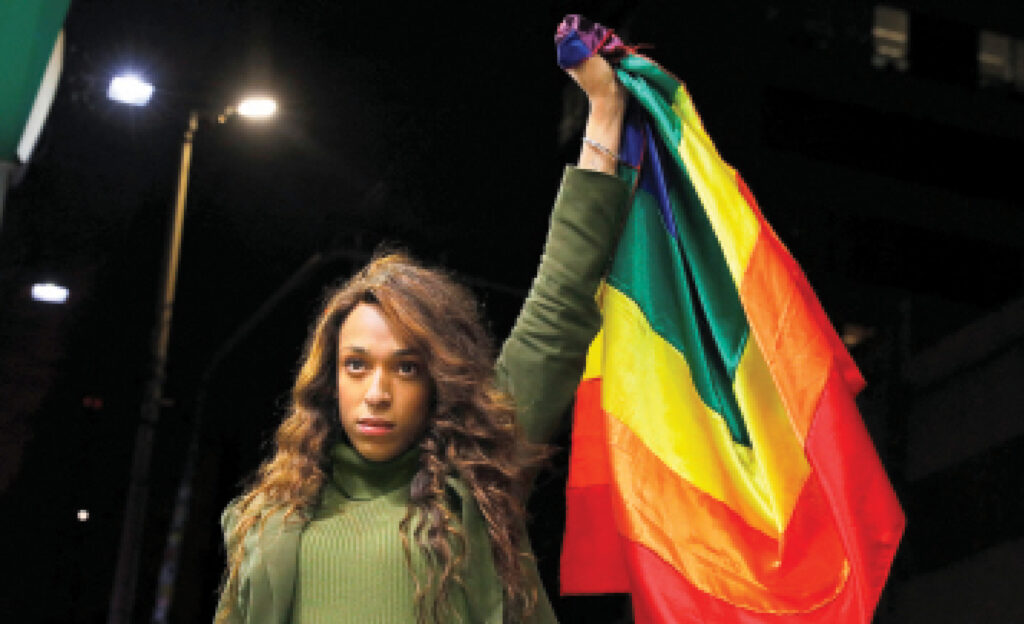

As a newly elected representative for São Paulo, Brazil’s most populous state, Hilton is one of the first transgender women ever to be elected to Congress in a country where 131 trans people were killed last year, according to a national organization, ANTRA, that advocates for trans rights. A social media sensation with more than 1 million followers on Instagram, a fashion icon, and a grassroots activist, she entered politics after years of living on the streets; her family shunned her when she came out as trans.

Hilton’s election reflects an uncertain moment in Brazilian politics in the wake of Jair Bolsonaro’s 2018-22 presidency, which saw repeated setbacks for transgender rights and other LGBTQ+ issues. As a member of the Freedom and Socialism Party (PSOL), Hilton is on the left flank of a Congress that remains clearly right-of-center. While she has faced several incidents of discrimination, including from congressional colleagues, she said she is trying to work with her peers to get as much done as possible.

“When I first arrived in Congress, even my party colleagues expected me to be aggressive, more in-your-face, you know?” Hilton told AQ. “But I am very pragmatic. I love fashion, and I know that there’s an adequate dress code for every situation. So, when I’m here, I’m following a different ‘dress code’ than when I’m at a rally or speaking with people on the street.”

LGBTQ+ rights are a priority for Hilton, but her personal experience also made her a vocal advocate for the rights of the homeless. “Brazil has become a country with a huge number of people living on the streets, and one with anti-homeless and dehumanizing policies,” Hilton said, standing in a corridor of the Senate on a morning in August. A 2022 study by the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais estimates the Brazilian homeless population at 206,000.

On the day she spoke to AQ, the congresswoman was negotiating with colleagues to advance a bill she wrote that would create a national employment program for the homeless. The next day, she succeeded, and the House approved the bill in a preliminary vote. It was her first win in Congress, six months into her first term.

Hilton, 30, attributes her electoral success in part to a growing wish among Brazilian youth not only for political renewal but also for the representation of minorities. “I believe the setbacks that we had in the last few years really made the population understand that participating in elections and discussing politics is important, and so is choosing whom to vote for,” she said.

Hilton also has a talent for turning her social media platforms into her main campaign asset. Her feed on Instagram is a mix of high-fashion photoshoots, clippings from news stories, clips of interviews, and videos about daily life in Congress. On July 29, for example, she posted a reel about her trip to the U.S. during a parliamentary recess in Brazil, complete with Beyoncé’s “Already” playing in the background. The post had over 40,000 likes.

“I always say that the youth, especially the LGBTQ+ youth, is constantly looking for an icon, a pop diva. It’s their universe; it’s ingrained in them. So, I try to replicate that in politics as a way to bring them closer. And I think it’s working.”

The new left

Hilton’s trajectory in politics began as she joined the student movement at Universidade Federal de São Carlos in São Paulo’s countryside, where she studied education and gerontology before eventually dropping out to start a political career. Before that, she lived as a sex worker on the streets of São Paulo for six years. Sex work is the main occupation of Brazil’s trans population, with ANTRA estimating that 90% of trans women are in that line of work.

Born to a poor, evangelical family in the outskirts of São Paulo, Hilton was raised by her mother and grandmother until her teenage years, when the family tried to send her to an uncle’s house in the countryside to “cure” her of “homosexuality.” She moved back in with her mother after a couple of years, but the fighting led to her being disowned.

This, too, is not uncommon for trans youth in Brazil. According to an assessment of the transgender and nonbinary population made by São Paulo’s City Hall in 2021, 47% of transgender women left their parents’ homes because of recurring arguments.

But Hilton’s trajectory began to turn when her mother realized she had made a mistake and welcomed her daughter home. She resumed her studies and eventually was given a place at a federal university. In 2020, she ran for city council in São Paulo. She obtained more than 50,000 votes and drew attention from the media as the first trans woman to be elected to the council. Last year, she again made headlines as one of the first two transgender representatives in Brazil’s history. (Duda Salabert, a former teacher from Minas Gerais, was also elected.)

“In the U.S., the social agenda, such as equal marriage rights and women’s rights, is largely related to the left in general. In Brazil, you had some leftist parties that were more able to capture the interest in that than others,” said Graziella Testa, a professor at Fundação Getúlio Vargas who researches legislative elections and performance.

The growth of interest in issues such as racism, gender inequality and other minority rights has propelled not just Hilton’s career but those of a host of others, including Sônia Guajajara, now minister of Indigenous populations under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. But in office, Lula has so far largely refrained from tackling social issues head on, a tendency that likely reflects his caution in the face of a powerful right wing.

That also explains why parties like PSOL, to the left of Lula’s Workers’ Party, keep growing. “There are people who represent this agenda in the Workers’ Party, of course, but the party wasn’t able to house these demands organically inside it. Other parties like PSOL are better at it,” Testa noted. PSOL was founded in 2004 by a group of representatives emerging from the Workers’ Party following a clash over political strategies.

“As a newer party, PSOL also has more space for new leadership and new candidacies to flourish,” said Testa. “Inside political groups, there is a line of those waiting for a turn to run for something. So maybe PSOL had fewer people in that line.”

A polarized Congress

Testa sees a link between the rise of the far right and the decline of Brazil’s traditional stronghold of center-right voters, the Brazilian Social Democratic Party (PSDB). When the PSDB began to falter, she said, the more extreme and vocal types of the right started to gain traction. “The far-right voter is very vocal, and they also have advantages in terms of campaign financing. And a part of these now-stranded voters from the center-right have turned to them,” she said.

This often makes Congress a battlefield. “I think it’s toxic,” laughed Hilton when asked about what she thinks of the environment in the House. Then she became serious. “I think it’s tiresome and even sometimes discouraging because you get to see how the dynamics of politics are carefully arranged by the groups in power. But it can also be very exciting because it pushes me toward everything I believe and the politics I want.”

Congress can be a hostile environment for politicians who don’t fit the male, white, cisgender and heterosexual norm. The Senate’s first female bathroom was built in 2016. In the House, maternity leave was counted as absence from sessions until 2021. For the two trans women members, transphobia is a reality. In April, Nikolas Ferreira, a congressman from Bolsonaro’s party, took to the House floor sporting a blonde wig and claiming to consider himself a woman. He insisted he would refuse to use female pronouns when referring to his colleagues Hilton and Salabert.

“First of all, I think it’s gross that there are still Brazilians who would vote for this type of hateful person,” said Hilton. Many did: In 2022, Ferreira was the top-voted candidate in the country with more than 1 million votes, surpassing even Bolsonaro’s son Eduardo, who held the previous record. “But they do this to show off, so I try not to focus too much on that. It’s a strategy of demoralization, of distraction. So, of course, he needs to be punished, but I just don’t want to give him the attention he wants,” she shrugged.

The disciplinary inquiry opened to investigate Ferreira’s behavior in the House was shelved in early August. Neither Ferreira nor his press manager responded to requests for comment.

For Testa, the mere presence of Hilton and Salabert in Congress stretches the limits of male dominance there. “This coexistence is important even for the men who were never confronted with that reality before,” she said. “In the end, the inquiry didn’t move forward, but it set some limits as to what is acceptable to say. Maybe if there weren’t a transgender person there, we wouldn’t be talking about his transphobia at all,” she said.

Hilton said that while she can’t separate her politics from her trajectory, she doesn’t want to be seen as a niche politician. “My body is marked by certain identities, and that shapes the way I make politics, of course, but I constantly run from stereotypes,” she told AQ. “I’m here to fight for my view of how the country should be, and that is for all Brazilians.

—

Boldrini is a staff reporter at Folha de S.Paulo and the host of podcasts Caso das 10 Mil and Sufrágio.