This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Uruguay

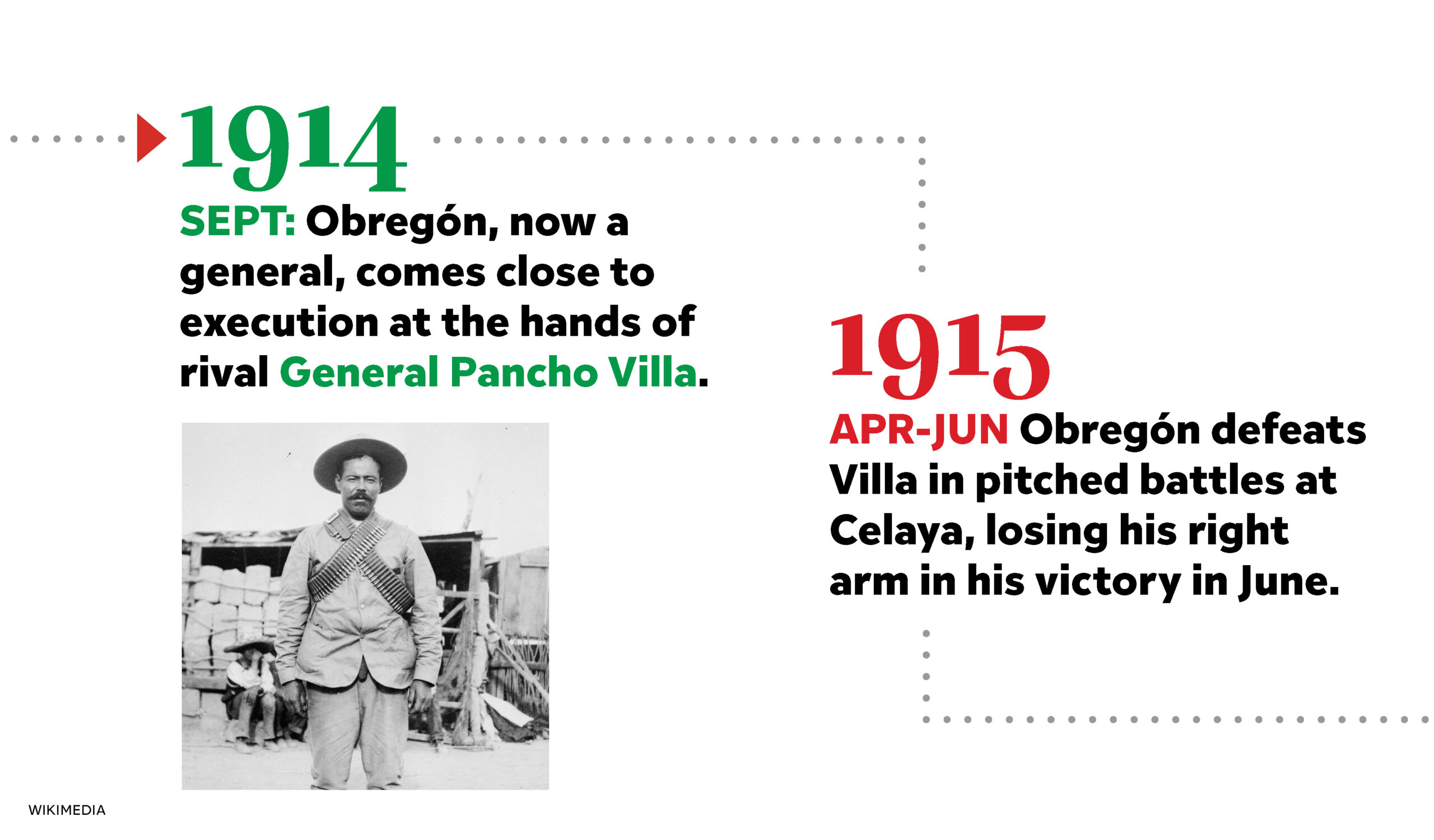

General Álvaro Obregón had a morbid sense of humor. His epic but victorious battle against General Pancho Villa’s formidable army in 1914-15 cost him his right arm, and the loss left him overweight and depressed. To compensate, he told jokes.

In 1919, he told a Spanish guest how one of his aides found the arm on the battlefield. As the story went, he instructed his aide to hold a gold coin in the air. “Immediately from the ground rose a species of bird with five wings. It was my hand—which, sensing a gold coin nearby, abandoned its hiding place in order to grab it.” Aware that this story might open him to charges of corruption, Obregón backtracked: “Here we are all … thieves. But I have only one hand, while my opponents have two of them.”

Humor served Obregón well. He eventually became the most powerful man in Mexico, known as “the undefeated caudillo” to his many supporters. But he had one great failing: He did not know when to stop. His bid for a second presidential term became one of the great tragedies of Mexican history, and had enduring consequences for the country’s politics. After Obregón’s fall, institutions increasingly served as a check on personal rule. In the ensuing decades, individuals could still amass great influence, but they would be required to alternate in power, in the hope of preventing a return to violence and anarchy.

The rise of Obregón

Before Obregón reached the apex of power in revolutionary Mexico, he had to endure many brushes with death—not just the loss of an arm. After joining the fighting in 1912, Obregón came close to execution at the hands of Pancho Villa in 1914. Five years later, Obregón slunk out of Mexico City just in time to avoid a court martial.

When an assassin threw three bombs at his vehicle in November 1927, Obregón knew he was living on borrowed time. He reportedly told the daughter of one of his allies, “I will live until someone trades his life for mine.” Prescient words, as it turned out.

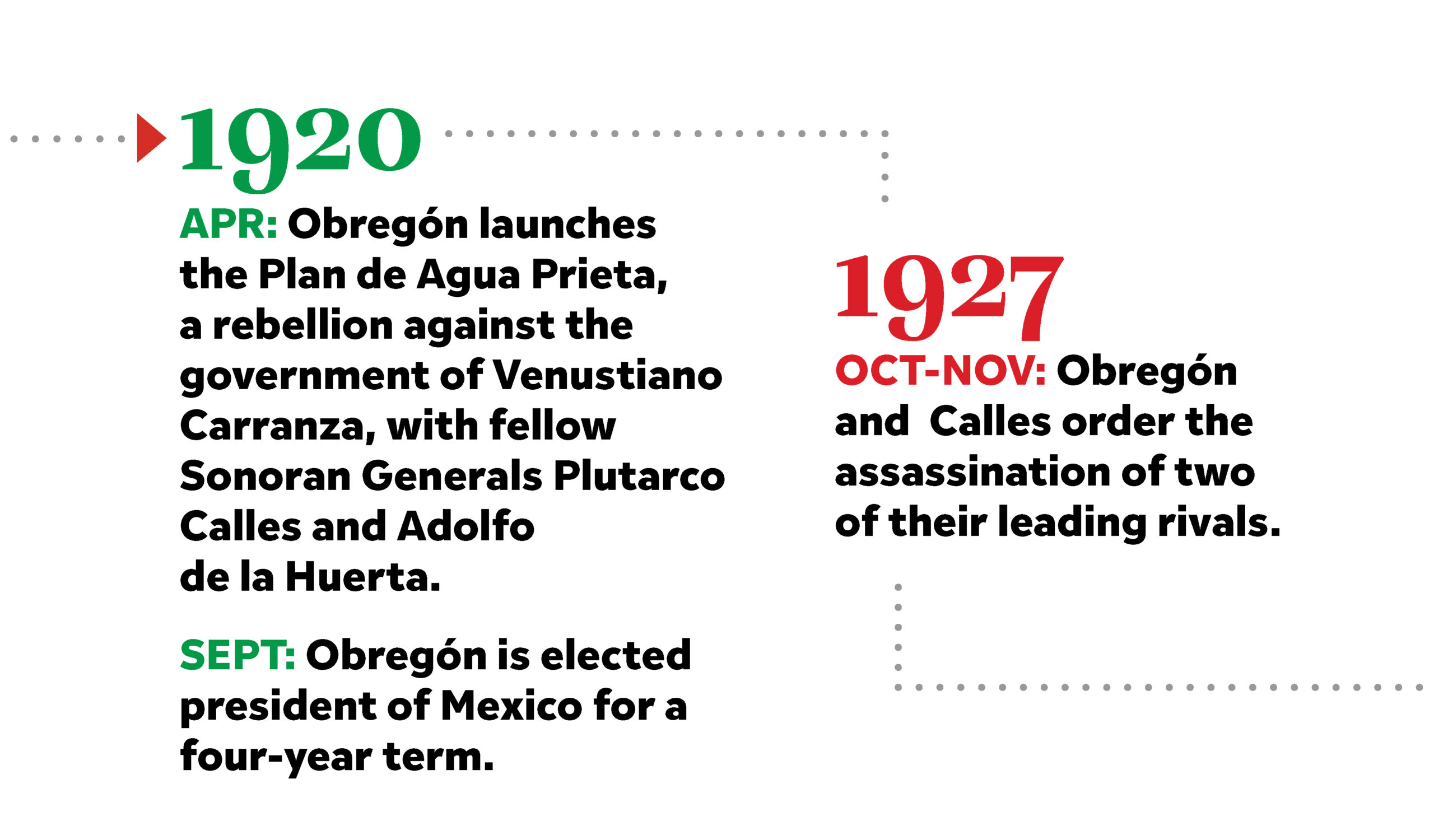

The Mexican Revolution began in 1910, when more than 100,000 ordinary Mexicans took up arms in a revolution against the rule of General Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911). Between 1 million and 2 million lost their lives or emigrated to the United States, fleeing from the violence.

The revolution’s motto was “effective suffrage, no reelection,” expressing a commitment to a democratic vote and a peaceful transition of power to new officeholders after a single term. But Obregón, a wealthy chickpea farmer who had joined the revolution only when it was bad for his business, saw in the revolution a chance for his own advancement. While he liked the reshuffling of the political deck, which brought opportunities to people like him, he did not see anything wrong with the authoritarian tendencies of Old Mexico. As he once put it, “Don Porfirio’s only sin … was to grow old.”

Obregón was a military genius who successfully adopted new techniques like foxholes and barbed wire against the federal army and Pancho Villa’s famed cavalry. He was also a charismatic leader who used his first presidential term to reconstruct a nation in tatters after 10 years of revolutionary warfare. His Sonoran ally Plutarco Elías Calles succeeded him as president in 1924. But Obregón wasn’t done.

Battle of the generals

First, Obregón directed his supporters in the legislature to clear the way for him to run for another term. In October 1926, the constitution was amended to allow multiple nonconsecutive presidential terms. Mexicans were alarmed, fearing that Obregón would alternate in the presidency with Calles to rule Mexico indefinitely.

But Obregón still had some loose ends to tie up. Between him and another term stood two of his fellow Sonoran generals. One was Arnulfo R. Gómez, ally and understudy of Calles. The other, far more formidable, was Obregón’s own childhood friend and comrade-in-arms, General Francisco R. “Pancho” Serrano. Serrano had accompanied the caudillo during most of his battles, and he was a part of Obregón’s family: His sister was married to Obregón’s eldest brother.

In fact, it was Serrano who had helped persuade Pancho Villa not to execute Obregón in 1914. As Obregón once reportedly told Serrano’s mother, “Pancho is my brain. Without Pancho, I am worth nothing.” And Serrano had significant backing in the army.

But Serrano also had significant liabilities. Even by the standards of the military patriarchy in 1920s Mexico, he lived a lifestyle of dissipation. He liked to frequent brothels and casinos. According to a U.S. military intelligence report, one of his mistresses lived in his house along with her mother, while his wife lived in Los Angeles. In the words of a fellow general, “This valiant and meritorious military leader … could never impose on himself any discipline or reserve that would prevent the adverse notoriety … inappropriate for his destiny and his future.”

Gómez and Serrano declared their candidacies before Obregón did, and for a while in the summer of 1927, the 1928 elections looked set to feature a thrilling competition between the three generals. But it was not to be.

Worried that such a competition would split the army and result in violence, Calles sent Serrano to meet with Obregón. But the meeting didn’t end in agreement, and Serrano and Gómez went on to launch a joint campaign against Obregón, though without deciding which of them would be the candidate.

The campaign rhetoric turned nasty. Citizens targeted Obregón and Calles with acerbic wit—always an important political weapon of the oppressed. Opponents invented anagrams of the two patriarchs: vengo a robarlo (“I have come to rob you”) for Álvaro Obregón; and el turco pescó la silla (“the Turk nabbed the presidential chair”) for Plutarco Elías Calles, who was rumored to be of Turkish descent. (His ancestors, in fact, were Spanish.)

Convinced that Serrano and Gómez were conspiring against them, Calles and Obregón launched a preemptive strike. On October 3, 1927, army officers arrested Serrano in Cuernavaca. Near Huitzilac, halfway to Mexico City, Serrano was executed on Calles’s orders.

Gómez took flight eastward toward Veracruz, but in early November, the army caught up with him. On November 4, they found him hiding in a mountain cave and had him shot by a firing squad—in a graveyard, of all places. Though Calles ordered the killings, there is no question that Obregón either masterminded or supported them.

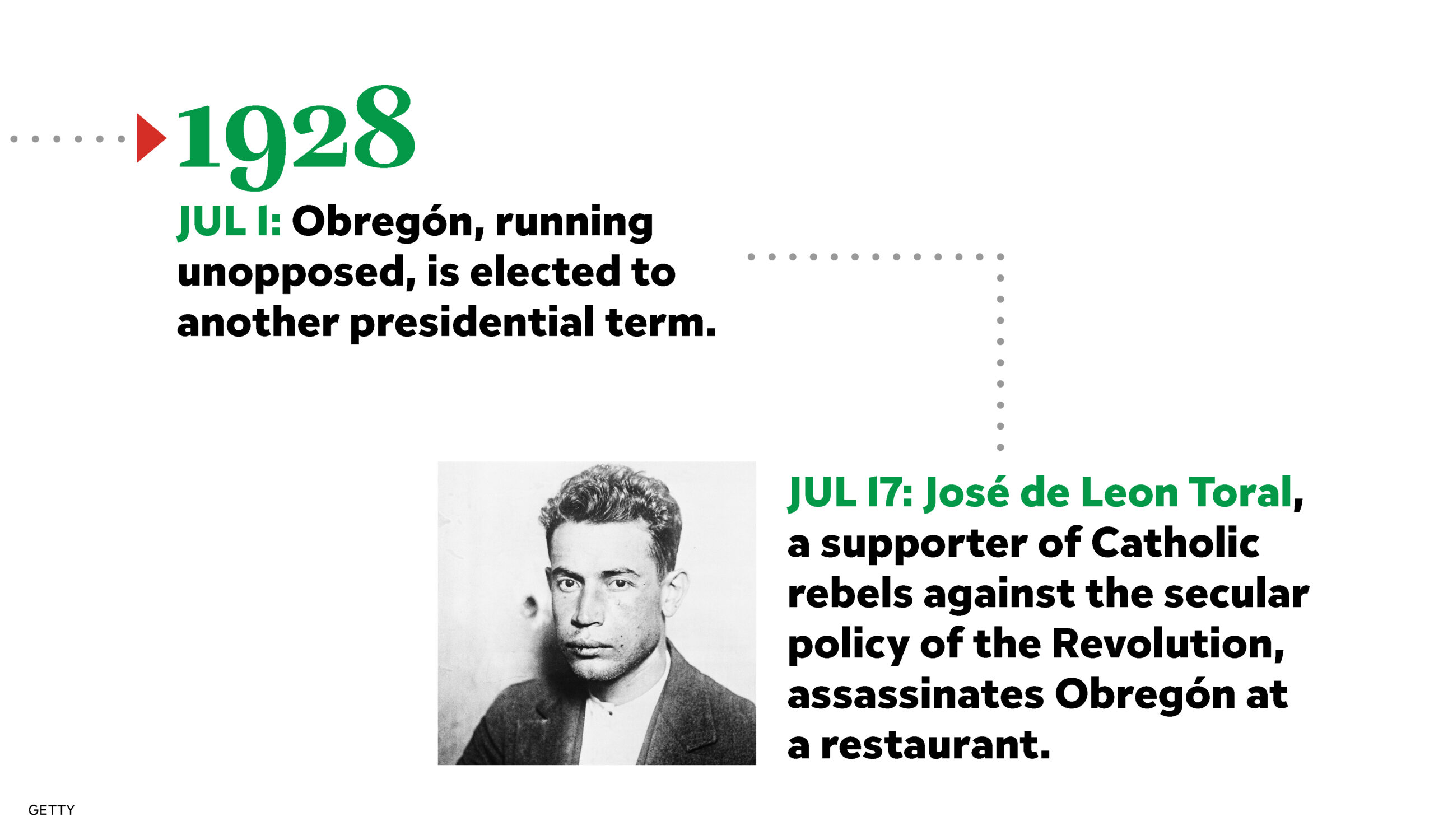

After the murder of the opposition candidates, Obregón coasted to victory unopposed in the 1928 elections. But the revolutionary regime had been unmasked as more of the same, at least when it came to presidential politics. Just like Porfirio Díaz, Calles and Obregón had eliminated the opposition—and in some ways, their deeds were worse, since they targeted allies, friends and, in Obregón’s case, a member of his extended family.

But Obregón soon got his just deserts. On July 17, 1928, he attended a luncheon in his honor at the restaurant La Bombilla in the Mexico City suburb of San Ángel. While the orchestra was playing Obregón’s favorite piece, “El Limoncito,” a young man posing as an artist worked his way around the table. José de León Toral approached Obregón and showed him his portrait. Obregón saw the sketch and began to laugh.

When the caudillo returned his attention to the food, León Toral took out his pistol and fired six shots in Obregón’s direction. Five found their target. Dead instantly, Obregón fell face forward into a plate of roasted goat and then to the ground.

Many Obregón supporters did not believe the official “lone wolf” theory of his assassination, believing that Calles’ government had murdered him because he had become so powerful. Reports of 13 to 19 entry and exit wounds on Obregón’s body led to rumors that others in attendance also fired on the caudillo once León Toral had begun to do so. At the very least, someone at the lunch might have looked the other way and failed to alert security to the presence of the strange, shy artist.

Mexican politics in the caudillo’s wake

What we do know is that Obregón’s assassination changed the course of Mexican history forever. Responding to rumors that he would use the emergency to remain in power, Calles announced that he would never serve as president again following the end of his term in November.

This placated Obregón’s supporters, some of whom blamed Calles for the murder.

Even more importantly, the fact that all three major presidential candidates died violent deaths prompted a fundamental rethinking about the future. Mexico needed to move beyond personalistic allegiances and toward a functioning party system. Calles knew that he could wield power behind the scenes in such an arrangement, just as Obregón had done during Calles’s term. Calles therefore warned his audience, “I do not need to remind anyone of how the caudillos obstructed … the formation of strong alternative means by which the country might have confronted its internal and external crises.”

Mexico was, Calles believed, a country in transition from a “country of one man” to a “nation of institutions and laws.” Later in 1928, he and his allies created an organization, the Partido Nacional Revolucionario, that soon became the most powerful of these institutions. This party, now the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI ), exercised an effective monopoly on power in Mexico until the end of the 20th century. Its powerful presidents, serving nonrenewable six-year terms, preserved the party’s dominance through election-rigging and, when necessary, with political violence—as in the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre. This system proved more stable than the personalistic rule of previous periods.

But today, the PRI is a pale shadow of its former self. Its candidate commanded just 16.4% in the most recent presidential election in 2018, when current President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) triumphed easily over a fractured field. Concerns over Mexican democracy have risen as AMLO concentrates personal power, attacks established institutions such as the National Electoral Institute and seeks to put the military in charge of everything from tourism to infrastructure and security.

The temptations of the personal style of politics remain. But a look back at the tragic end of Obregón’s career shows the danger, and the folly, of a politics based on men rather than laws.

__

Buchenau is a professor of history at UNC Charlotte and the author of The Last Caudillo: Álvaro Obregón and the Mexican Revolution (2011).