Across Latin America, 2021 is still being hailed as a year of recovery. After the region accounted for 28% of the world’s confirmed COVID-related deaths last year, and suffered its worst one-year economic contraction (-7.4%) since 1821 in the aftermath of its wars for independence, most politicians and business leaders believe the worst has now passed. Yes, recent outbreaks in Brazil, Chile and elsewhere have caused a new spike in deaths and related lockdowns. But, the theory goes, vaccine rollouts should gain pace as the year progresses. Most governments have seen their popularity remain steady or even rise, and there is little sign of the massive protests that were shaking the region before the pandemic forced everyone off the streets. “I think we’re very close to the finish line,” one politician recently told me. “It could have been so much worse.”

But several studies published this month tell a different story: COVID-19 has shattered Latin America to a greater degree than many appreciate, and the sense of complacency that currently prevails in many capitals may be dooming the region for years to come. These studies show just how badly the pandemic has hit vulnerable groups like women, Afro-descendant people and informal workers, and warn the recovery seems likely to leave them even further behind. Latin America’s banks may be more vulnerable than generally known, while happy talk about supply chains relocating from Asia in the wake of the crisis so far remains just that. Schools are still closed in greater numbers than anywhere else in the world, risking a true “lost generation” – and leaving economies without a clear engine for growth as the region rapidly ages in the 2020s and 30s.

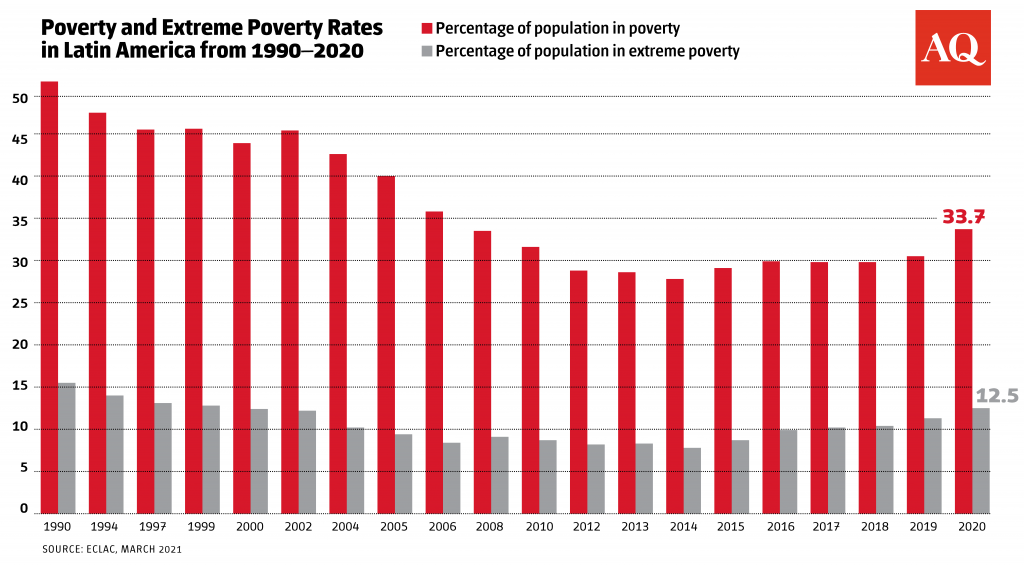

It is indeed true that things could have been worse. Emergency aid in the form of cash (and “in-kind”) transfers reached 61% of Latin Americans in 2020, roughly triple the percentage that received such payments prior to the pandemic, according to a new report by ECLAC, the UN’s Latin America-focused economic body. The size and duration of the aid varied widely, and defied ideological stereotypes: Right-wing governments in Brazil and Chile offered the most generous support, more than twice as much in relative terms as their peers in Mexico, Argentina and Bolivia. Overall, poverty in the region “only” rose about three percentage points, to 33.7% of the population. That was the highest level since 2006, and a tragedy in itself. But ECLAC calculated that, without the aid programs, poverty would have increased more than twice as much.

Just beneath the surface, however, lie vast and growing disparities in what was already the world’s most unequal region. The richest quintile of Latin Americans saw their income decline just 7% on average in 2020, while joblessness barely increased at all. Compare that to the bottom quintile, which saw their income fall a staggering 42% while unemployment rose five percentage points. Women dropped out of the labor force at a greater rate than men in nine of 12 countries studied by ECLAC, which also found that persons of African descent in Brazil were only half as likely to be able to do their job via teleworking as whites. Arguably the biggest disaster of all was faced by the more than half of Latin American workers who labor in the so-called black market. In countries including Mexico, Brazil and Costa Rica, more than 70% of total job losses in 2020 occurred in the informal sector. Such workers already had little to no safety net; they immediately faced hunger, homelessness or worse.

And this is where the wheels really start to come off the recovery story. Both ECLAC and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), in its newly published annual macroeconomic report, highlight the likelihood that, if present trends hold, the economic rebound will be weak – and most future jobs will be created in the informal sector. That means a more precarious life for millions of Latin Americans compared to before the pandemic, and poverty rates that will remain stubbornly high. Meanwhile, most governments including Brazil’s have pared back or eliminated the aid programs of 2020, leaving millions without protection, largely because of fears of a worsening fiscal crisis. The fears are real: The region’s average public debt soared from 58% to 72% of GDP last year, and the IDB’s baseline scenario is that it will continue to rise, to 76% by 2023.

It’s worth noting the United States would be facing a similarly bleak scenario, were it not blessed with the world’s reserve currency – and thus the (apparent?) ability to print trillions of dollars without major consequence. But Latin America, with its long history of stiffing creditors, is on a shorter leash than most. It’s still unclear whether this will result in a wave of sovereign debt defaults like the 1980s; but the IDB report pointedly included a section looking back at that “lost decade,” essentially arguing that if restructurings are to happen, sooner is better. The IDB also warned of a “false sense of security” in the region’s broader financial system, citing several warning signs in recent months despite ostensibly healthy balance sheets. Inflation is rising in some countries even with economies still flat on their back; Brazil raised interest rates last week for the first time since 2015, by 75 basis points.

Finally, there is the tragedy underway at schools. Some 114 million students in Latin America and the Caribbean, or roughly 80% of the total, are still unable to attend school in-person, according to a report released Wednesday by UNICEF. That’s by far the world’s highest number, and the expectation is that at least three million of them – and possibly many more – won’t ever come back. Only a fraction of students have been able to effectively attend school via the internet, and studies suggest millions of secondary school students have already lost basic reading and math ability. This is reversing one of the region’s great success stories (and economic growth engines) of the past 30 years, the growth in primary, secondary and university education. The World Bank estimated this month that, given current trends, the education crisis could shave about 10% off Latin Americans’ future earnings, an unfathomable $1.7 trillion.

As always with Latin America, it’s important not to fall into the trap of fatalism. As I wrote last October in making a “less apocalyptic” case for the region, history shows it has always been a place of ups and downs. It’s possible the recent spike in prices for oil, copper and other commodities will boost the exporting economies of South America, while a post-stimulus economic boom in the United States would give an immediate lift to Mexico and Central America. A few governments do seem to understand the magnitude of the challenges, while some in the private sector, civil society and media continue to agitate for change. But virtually all the other reasons for hope I cited last year have eroded, especially education, in the face of overwhelming inaction.

Indeed, it’s hard to escape the following conclusions: That many Latin American elites, having come through the pandemic more or less unscathed themselves, are failing to understand that 2021 is not the time to relax and declare imminent victory over the pandemic. That most of the region’s presidents and other political leaders, on both left and right, seem content to recycle failed ideas from the 1960s and 70s, or focus on upcoming elections, instead of urgently pushing the modernizing reforms that could boost investment and, thus, the creation of quality jobs. That the region’s most vulnerable, having been somewhat shielded in 2020, may now be largely on their own. Growth in Latin America was stagnant for years even prior to the pandemic, and per-capita income has now fallen all the way back to levels of the mid-2000s, according to ECLAC. It’s a region that is not on fire – not yet – but that seems to be sleepwalking toward a long-term decline in income and quality of life. Unless its leaders wake up, and soon, we may well look back at the decisions made, or not made, during 2021 as being even more disastrous than the events of 2020.