This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Latin America’s election super-cycle

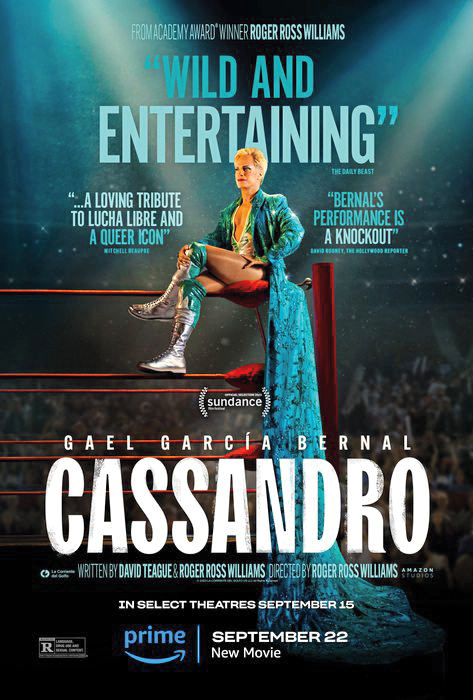

For most of its history, Mexican lucha libre has been the domain of brazen machismo. A new biopic, directed by Oscar-winning documentarian Roger Ross Williams and starring Gael García Bernal, revises this narrative. Cassandro tells the life of Chicano and gay wrestler Saúl Armendáriz, a now-beloved icon of the ring who earned success by defying prejudice and convention.

At the start of the film, Armendáriz wrestles as a rudo on the Mexican side of the border, in Ciudad Juárez. Rudos are the “heels” of professional wrestling: the bad guys who confront the good guys, also known as “faces.” In lucha libre, outcomes are mostly pre-established and fixed, turning matches into performed spectacles of “good” versus “evil.” As a rudo, Armendáriz always has to lose. But a new trainer injects new ambition, and Armendáriz realizes he could win by charming the crowds, if he were to craft a sufficiently captivating persona.

Cassandro

Directed by Roger Ross Williams

Screenplay by Roger Ross Williams and David Teague

Distributed by Amazon MGM Studios, Double Hope Films and Escape Artists

Starring Gael García Bernal and Roberta Colindrez

Mexico, United States of America

That persona became Cassandro. Under this new guise, Armendáriz becomes an exótico—a wrestler in drag. For his first act, he wears a tight-fitting red tank top and tiny shorts. In lieu of a traditional mask, he opts for makeup. Although he ends up losing, he elicits supportive cries from the crowd, teased and electrified by his risqué moves in between hits. Ensuing fights help crystallize Cassandro as a cheeky, flamboyant and enormously entertaining competitor.

Yet, for all of its delights, Cassandro also brings disappointment, sanitizing the tangled nature of a man’s choices and feelings in favor of Hollywood glitter and comfort. Consider the film’s dramatic climax: after a streak of good luck, Armendáriz lands a lucha with el Hijo del Santo, the son of Mexico’s most iconic and legendary luchador. Nervous and excited, he spends the night before at a club, drinking and doing drugs and hooking up with other men. Once back in his hotel room, he cries and receives consolation from his trainer. The real-life Armendáriz, back in 1991, slit his wrists and nearly died in anticipation of the fight. He still made it to the ring.

Biopics, of course, have no obligation to always stick to the facts, and for good reason. An exact portrayal would be both impossible to accomplish and tedious to watch. In a recent interview, Williams claimed he wanted to focus on “Cassandro’s glory” as a “shining superhero,” rather than contributing to the “many negative stories about the LGBTQ+ community” already out there. Yet the emphasis on positivity comes at the cost of complexity and depth, ultimately hiding whatever may be disagreeable to audiences in Armendáriz’s story.

Cassandro rightly celebrates Armendáriz for wrestling as an openly gay man and paving the way for others like him. But the suggestion that his sexual identity lies at the heart of his success as a luchador only distorts the violent macho attitude that he is forced to inhabit, just like his adversaries. When he hears, “And now, Cassandro!” Armendáriz said years ago that his “man side comes out. ’Cause I gotta be a man in the ring.” This sentiment would have made for a more fascinating character study, but Williams eschewed that option.

The Armendáriz that viewers of Cassandro are left with is polished and sensational. In real life, he has survived broken teeth, multiple concussions, a lower body paralysis and more than half a dozen hospitalizations. He understands that lucha libre “is about getting hurt,” and he has “had to make peace with that pain.” One story belongs to a feel-good fantasy, the other to the stuff of life.