BOGOTÁ — Since day one at the Casa de Nariño, Colombia’s President Gustavo Petro sought to push a radical transformation of Colombia’s health system. As one of his top priorities, he drove a reform proposal to the legislative power last year, hoping to score a political victory with understandable societal echo. But last week, after a protracted process in Congress that led to a Cabinet purge, senators shelved the bill, dealing a sizable blow to the nation’s first left-leaning president.

Against this adverse scenario in Congress—which will likely continue over the rest of his term and affect his other legislation priorities—Petro will use all the executive’s legal and constitutional prerogatives to push his agenda on key fronts, such as overhauling the country’s healthcare, pensions, utilities, and education models.

Reflecting this, last week, the Superintendent of Health (Supersalud), the entity overseeing private healthcare, replaced the executive board of the country’s two largest private health insurers, known by the Spanish abbreviation EPS. The state will replace their leadership for a year to redress their funding and management deficiencies and ultimately prevent their dissolution. (A third provider voluntarily requested to be dissolved permanently.) This triggered a fierce media and political backlash, with opposition leaders, the private sector, and even some former members of Petro’s cabinet criticizing an increasingly “dictatorial” drift under his administration.

This resort to heavy-handed executive action, legally conforming but lacking consensus with other parties and private agents, highlights the Petro administration’s increasing desperation amid limited results on major campaign promises for reform—and we should expect more of the same to come. However, Colombia has a robust system of checks and balances, and both courts and other independent government agencies can be expected to rein in any potential government’s excesses. However, more profound institutional polarization and regulatory uncertainty may result in critical sectors over time.

Anatomy of a reform

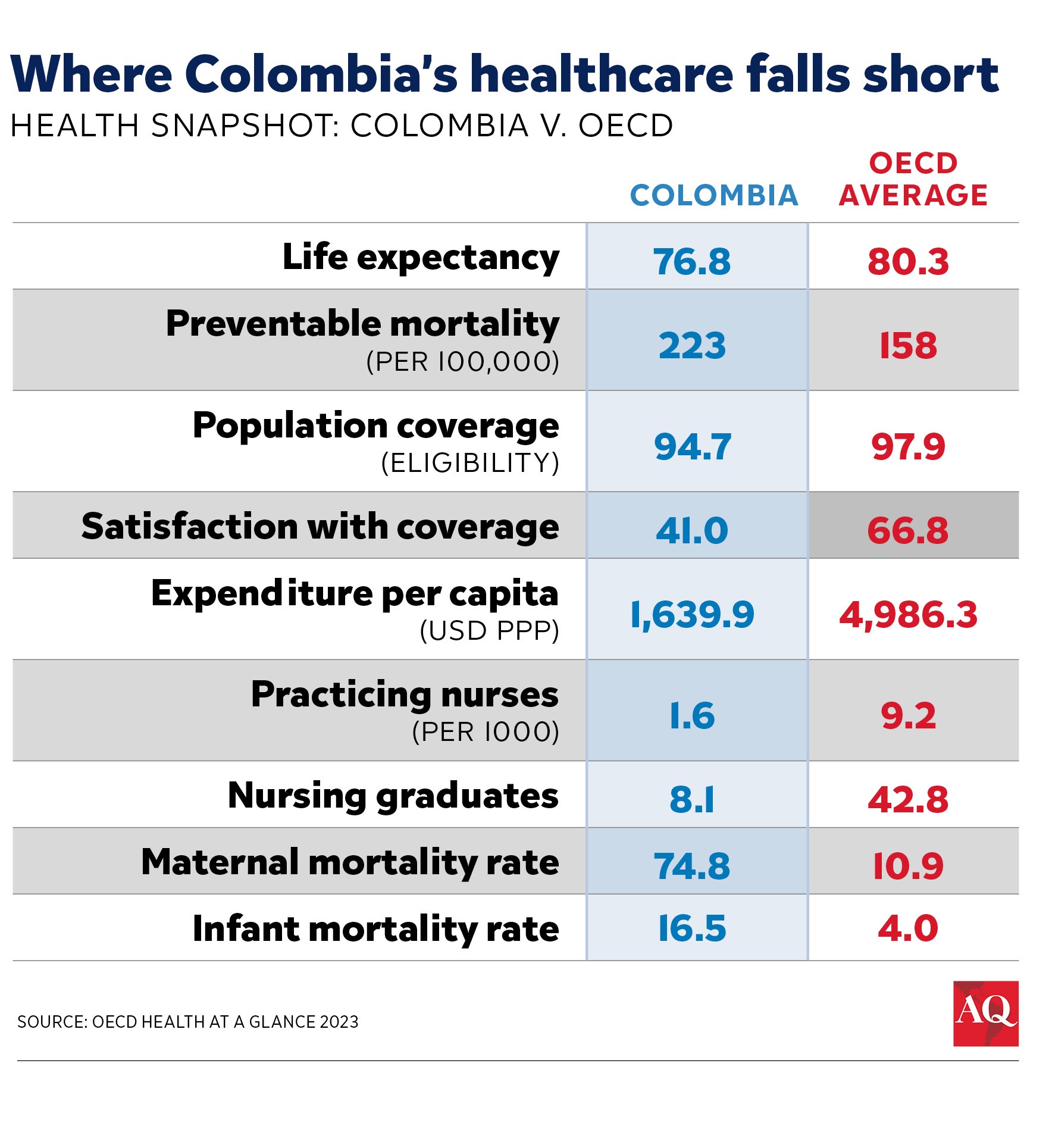

Petro promised an overhaul of the country’s health system in his 2022 campaign. While the current model guarantees 95% of citizens coverage with a robust benefits package, it faces serious quality, management, and funding deficiencies that undermine health outcomes relative to other OECD countries. As the president sees it, profit-making private insurers are largely to blame.

In February of last year, the government sent to Congress a health reform that sought to enhance the state’s role in financing and providing health services at the expense of private providers. However, opposition from centrist parties in Congress led to the Senate finally sinking the bill last week—just as Supersalud announced the interventions in two of the largest private insurers

These events point to the political and regulatory trajectory the country is likely to take during the two remaining years of Petro’s administration. On healthcare—as on many other issues—Petro has adopted an unyielding approach to governing and policymaking, eroding his chances of building far-reaching consensus that would enable the profound transformations Colombia does need.This attitude and the rigid vision that Petro has of these reforms have led his government down a path of increasingly volatile, deficiently debated decision-making that, in turn, has exacerbated political polarization and regulatory uncertainty.

The healthcare intervention was justified on technical grounds—including poor financial performance and service provision. But the move fell short on key procedural criteria. Supersalud should have first jointly designed with the health insurer an improvement plan; if it failed, the latter should have been subject to a period of enhanced oversight; and only then, if the expected results were not reached, an executive intervention should have been put in place. And there are other private providers with much worse financial performance and service provision indicators than Sanitas and Nueva EPS. Supersalud’s actions suggest a new cycle of poorly debated and even technically flawed government decision-making, likely to embrace other core sectors of Petro’s vision: mining and utilities.

A test for robust institutions

Amid the fierce backlash provoked by Petro’s intervention in the private healthcare sector, some cited fears of a system collapse and severe erosion of democratic institutions. These are likely overblown.

Interventions such as the one enacted by Supersalud align with the country’s current regulatory framework. There are precedents for such takeovers in the past two decades, under right and center-right governments and even under the current administration last September. Outcomes have been mixed: Some have effectively redressed funding, management, and service provision shortcomings, and others have resulted in their definitive liquidation.

Thus, this recent set of regulatory intervention decisions does not automatically pave the way for permanent state takeovers. The results will depend on the specific management and funding deficiencies each provider faces and the strategies adopted by the temporary public comptrollers to address them.

And in general, control agencies and other branches will effectively counterbalance executive overreach or potentially arbitrary measures. If considered improper, executive decisions will likely be challenged by the opposition and business associations at the Council of State –Colombia’s top court for disputes arising from Executive conduct or omissions, which is enabled to overrule government actions or be overruled by the Constitutional Court due to any procedural or substantive flaws. Despite acute regulatory uncertainty and political polarization in 2024, Colombia’s rules governing critical sectors will unlikely see radical or definitive changes over the next two years.

Still, there are risks that these clashes will politicize regulatory institutions over the next two years. Just as the government’s volatile, technically unsound, and improvised decision-making will probably become prevalent—motivated by growing frustration and inflexibility—control agencies’ oversight will probably become more openly politicized “to contain Petro.” In turn, this is likely to lead to a moderate erosion of the separation of powers and judicial independence—though not one that rises to the level of serious threats to democratic institutions and the rule of law.

—

Lizarazo is a senior analyst for the Andean region in Control Risks’ Global Risk Analysis practice, based in Bogotá.