Photographs by Nicolas Villaume / Text by Rich Brown

This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on COP30

CORDILLERA BLANCA, PERU—The glaciers of Peru’s Andes are vanishing. They are at least 40% smaller today than they were half a century ago due to rising temperatures. New research indicates that ice loss in the Andes could eventually threaten water supplies for 90 million people, and reduce river flows in the Amazon basin by 20% with serious consequences for the Amazon’s forests and the global climate.

But water shortages due to ice loss are already common in many mountain communities. Meltwater that their crops and livestock have depended on for centuries is increasingly scarce. And as glaciers retreat, they leave another grave problem behind: acid rock drainage. When rock formations are uncovered for the first time in millennia, contact with water triggers chemical reactions. These reactions create sulfuric acid, which eats further into rockfaces and releases toxic heavy metals that were once trapped. All this ends up in local waterways, leaving streams, rivers, and lakes acidic and contaminated.

In Peru’s Cordillera Blanca, acid rock drainage has taken a significant toll. Crops have failed, and fish and livestock have died. The city of Huaraz, the capital of Peru’s Áncash Region with a population of around 150,000, has already been forced to turn away from two watersheds it used to tap for fresh water due to heavy metals contamination—only to see its third fallback option show signs of deterioration.

Now, scientists and local communities have joined in a race against time to develop bioremediation strategies that could turn the tide and produce clean water. These strategies use living systems of plants and microorganisms to filter out acidity and heavy metals in streams and wetlands. Their efforts to combine scientific measurement with ancestral knowledge of local plant life and water flows are showing promise. If they succeed, they could provide a model for the growing number of high-altitude communities around the world struggling to survive this new threat

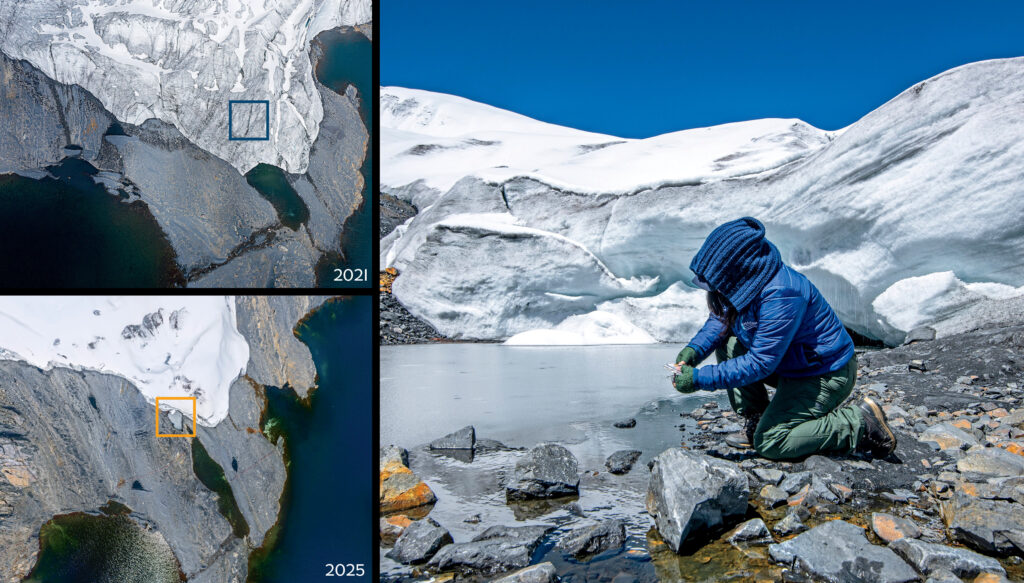

Left: Aerial photos taken four years apart show the rapid retreat of the Pastoruri Glacier. The orange box shows where the above photo of Gonzales Llontop was taken.

Inset: Gonzales Llontop processes molecular plant samples in an Inaigem laboratory. Samples from Lake Shallap, once a source of water for Huaraz, have registered a highly acidic level of 3.2 on the pH scale—more acidic than tomatoes or black coffee.

Tags: Andes, Climate change, Peru

)