This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on supply chains

Mercado Libre is Latin America’s original “garage-to-Nasdaq” story. The iconic e-commerce and financial technology (fintech) startup was built from scratch in 1999 and became a regional giant with a net income of $7 billion in 2021. But its cofounder Hernán Kazah and its ex-CFO Nicolás Szekasy believe one of the company’s most important legacies is that it inspired people across the region to take the risk of building startups.

Kazah and Szekasy founded Kaszek Ventures in 2011 to invest in those people, during an era when the venture capital (VC) world was largely ignoring Latin America’s potential. They have stayed on as Kaszek’s two managing partners, and the firm has since become one of the region’s largest early-stage investment funds, raising upwards of $2 billion. It has invested in more than 100 companies, including 16 of the region’s 42 unicorns—startups that have grown to a value of over $1 billion.

Kazah and Szekasy, both from Buenos Aires, credit their success at recognizing startups’ potential to their own experience as entrepreneurs, which they have leaned on to develop their investing strategies. “We’ve been in the trenches since the beginning of the technology boom,” Szekasy told AQ.

Their story, and their insistence on taking the long view on Latin America even during times of crisis, has added meaning today as the region’s startup world endures a new wave of turmoil.

As international financial markets reel, tech stocks plunge and fears of recession grow, startups throughout the region are laying off hundreds of employees and what’s left of their teams are bracing for lean years. Yet Kazah and Szekasy remain bullish. Their experience has taught them that Latin America’s outsized macroeconomic and social challenges tend to inspire entrepreneurs focused on equally outsized solutions—and that rewards can accrue to investors who are patient enough to ride out the inevitable storms.

Indeed, from the trenches at Mercado Libre, Kazah and Szekasy weathered the tech bubble collapse of 2000 and the global financial crisis of 2008. They operated for over five years without turning a profit, at times unsure whether the company would survive.

But they believed in the region’s potential and in themselves. Szekasy, now 57, credits his parents for instilling that drive in him. His mother fled the Nazis in Germany in 1936 and his father fled the Soviets in Hungary in 1948. “When you have to start from scratch in a new country, you’re an entrepreneur at heart,” he said. “The spirit of having to rebuild your life—thinking long-term—is part of what I saw and breathed at home.”

He graduated from Stanford Business School in 1991, before the internet revolution, and went to work for PepsiCo. But when Kazah asked him to join Mercado Libre when it was just getting off the ground, Szekasy quit his comfortable job with “no doubts at all,” he said.

Kazah had connected with Szekasy through the Stanford Business School network, having graduated at a very different time: 1999, with the internet boom in full swing. “Everyone at Stanford was talking about technology (and) starting businesses,” said Kazah, who is 51 today. “Professors were board members of startups and my classmates were students and founders of companies. It was terrific.”

Kazah and Szekasy said the crises they endured as the market oscillated wildly in the 2000s taught them three key lessons they deploy as investors and impart to startup founders: avoid shortcuts, think long-term and minimize dependence on external capital.

“They’re not going to get fooled by the grow-at-all-costs (mindset),” Carlos García, the founder of Kavak, one of the unicorns in Kaszek’s portfolio, told AQ. “What’s really constant with (Kaszek) is that no matter where the tide is, (they always) clear out the noise and focus on fundamentals.”

A region many ignored

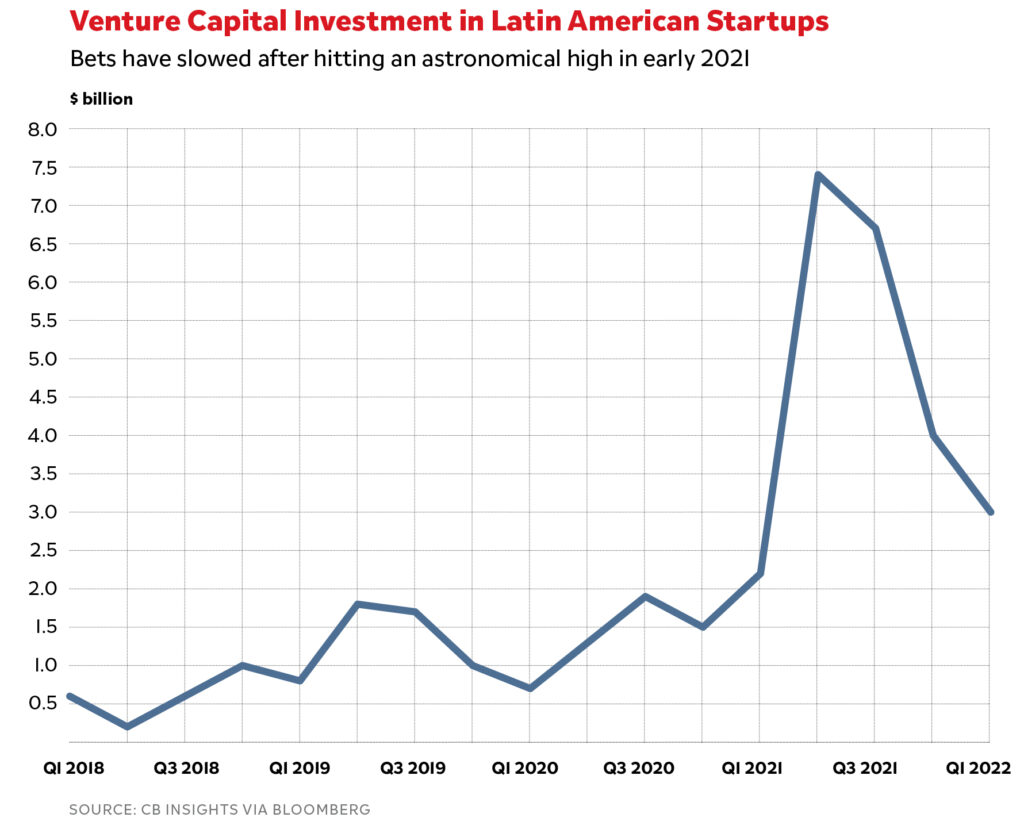

VC investment in Latin America exploded in 2021, briefly making the region the hottest VC market in the world. That VC investment peaked in the second quarter of 2021 at an astronomical $7.3 billion, more than the previous four quarters combined.

But the tide receded almost as quickly, as inflation and interest rates climbed and fears of recession deepened. Yet Kazah and Szekasy see an era of opportunity ahead despite a litany of global challenges on top of Latin America’s chronic volatility. “We’re sure that many Mercado Libres will emerge over the next 10 to 15 years in Latin America,” Kazah said. “In five or 10 years from now, I’m sure we’ll pass the mark we reached last year.”

They have already found success in a market that major U.S. venture capital firms overlooked a decade ago. “Kaszek had great timing going into Latin America, which the big VCs in the U.S. were ignoring,” said Gabriel Gruber, an Argentine entrepreneur, former central banker and cofounder of Exactly Finance, another Kaszek investment.

Ten years ago, Gruber went to Silicon Valley to raise money for a startup. “I went to see a couple of the big VCs and the answer was, ‘Latin America is too small for us, we don’t care about Latin America,’” he told AQ.

Kazah said the region is especially ripe for disruption due in part to its deep social inequities. Industries from health care to education to food leave huge swaths of the population behind, he said, putting creative use of technology and capital at a premium. Tech companies are seeking to cheaply and efficiently connect students to teachers, patients to health care providers, consumers to efficient supply chains and lower prices.

Startups often aim high because the problems they seek to solve are so profound. The idea for Kavak, a Mexican car sales platform, was born when García, its founder, got ripped off selling his car and then again when he bought a used one. Kavak has since become a hub for buying, selling, financing, servicing and insuring used vehicles throughout Latin America and in the Middle East. “We built like a super-app approach to do all this,” García said, “because the problem that we’re solving is 10 times deeper (in Latin America) than any other marketplace in the world.”

These kinds of big solutions to big problems are being built on a foundation of smartphones and fintech, which is helping middle- and working-class families in Latin America start to gain access not only to better services but to credit. “Almost everything comes down to fintech” in the tech and startup space, Kazah said.

Kaszek invested in Nubank—today the world’s largest fintech bank and another unicorn in their portfolio—when it was just founder David Vélez and his PowerPoint. Kazah and Szekasy saw the potential to tap into demand for credit from the large number of people in Brazil who had been overlooked by traditional providers.

But Nubank’s rise to challenge the region’s biggest banks was anything but certain. “We were concerned about what the central bank would do because fintech is highly regulated,” Kazah told AQ. However, he said, the country’s fintech policies showed that Latin American institutions have the potential to create models for both the Global South and the Global North.

Brazil’s central bank “has been very forward-looking, really focused on this mission of democratizing access to financial services” and facilitating competition while also protecting users from scams, Kazah said. The steps it took are likely to be replicated throughout the region, and Kaszek intends to fund the entrepreneurs who respond to the new opportunities this would create.

Upside of the downside

The inevitable waves of instability in Latin America, like the current one, can also have their upside. Too much VC liquidity splashing around often harms startups by encouraging them to raise funds based on concepts and potential as opposed to fundamentals. In flush times, teams can be tempted to push their products or services through marketing and other inorganic means instead of building a self-sustaining consumer base.

This is part of what Latin America saw in 2021, Szekasy told AQ. Now, he said, “the teams that have focused on doing the right things and building solid infrastructure will be there for the long term. Others that have been at all the conferences and panels and have been very visible but haven’t necessarily spent the time building their companies will be in a tougher spot.”

“It’s not that it’s always fair,” Kazah said. “But importantly, most companies will emerge stronger out of this.”

Gruber of Exactly Finance even speculated that layoffs in the Latin American tech and startup sectors will lead to more startups as talented people find time to develop their ideas. “I think there’s going to be a new generation of great entrepreneurs and great startups starting in 2022,” he said.

Kaszek is now deploying its fifth early-stage fund, of $475 million—perhaps the largest ever in the region, according to TechCrunch—and its second Opportunity Fund, of $525 million, for later-stage investing and to explore new investment vehicles. These include its first SPAC—special purpose acquisition company—in partnership with Mercado Libre, which Kazah expects will set another regional trend as SPACs become more common.

A SPAC is essentially a shell company that undergoes its own IPO so that it can then buy another company that becomes public almost automatically. SPACs often draw criticism for skirting regulations and due diligence and for the fees that their managers rake in. But Kaszek’s SPAC has “the right incentives,” Kazah said. “All the fees that you have with SPACs, in our case only kick in if we add value over time and the stock appreciates. If it doesn’t appreciate, we get zero.”

Beyond the inequities to be bridged, favorable central bank programs and the rise of fintech, Kazah and Szekasy see one more key indicator that Latin America’s tech and startup sectors will far surpass expectations: a profound cultural shift.

“If you go to a graduating class of engineering students in Brazil, 90% aspire to become entrepreneurs or join a startup, and very few want to become bankers or corporate managers,” Szekasy told AQ. Mercado Libre, Nubank and others have proven “the Silicon Valley metaphor that three kids in a garage could launch a company that would one day challenge the biggest incumbents, even in Latin America,” Szekasy said. “This would have been considered crazy not so long ago.”

The surging interest among young people in technology and startups will encourage them to try to tackle urgent global problems rapidly, Kazah said. “We are very proud of the technology ecosystem (that Kaszek helped to create) in the region.”

“What has happened so far is beyond anything we thought could happen,” Kazah said, “so we expect the coming years will continue to be extraordinary.”