MEXICO CITY — Mexico is a country historically fabled for its intellectual heft in Latin America and the world over. Nowadays though, public intellectuals seem far less prominent in public discourse and agenda-setting. Beyond some important caveats—including the fact that there is no dearth of intelligent Mexicans saying some very interesting stuff—two things have clearly changed to make the Mexican public intellectual a more diminished figure: the twin rise of the digital media economy and Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

The heyday of Mexico’s established public intellectuals seemed to be thriving well into the 21st century, led in large part by Enrique Krauze, who helmed the country’s most influential highbrow publication, Letras Libres. In self-congratulatory fashion, the magazine’s March 2014 edition was dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the birth of Octavio Paz, a Nobel Prize laureate in literature and a titan among titans of Mexico’s late 20th-century intelligentsia. Krauze inherited the mantle of preeminent public intellectual after Paz’s death on the cusp of the new millennium.

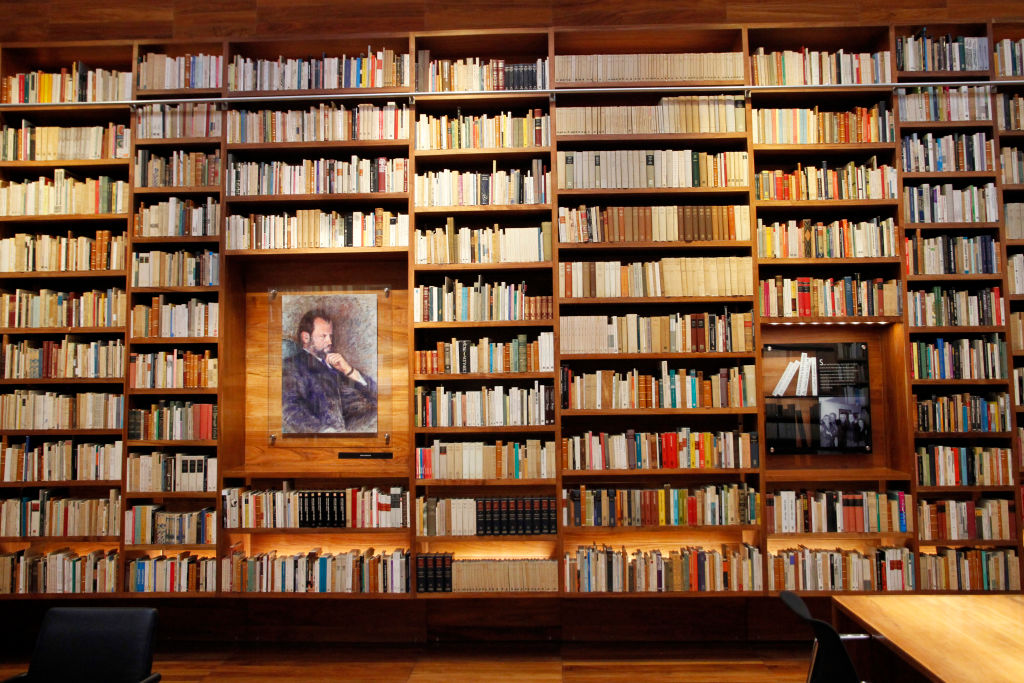

It was a time in which Mexico’s intellectuals loomed large over public discourse. In the early 2000s, it felt like every other edition of The Economist contained a quote from Krauze. Journalistic luminaries like Charlie Rose and Carmen Aristegui visibly suppressed their giddiness while interviewing the famed Mexican writer and diplomat, Carlos Fuentes. The internet was nascent and the most critical public debates often happened in prestigious printed magazines like Letras Libres, Nexos or La Tempestad.

How sudden the change was.

By 2018, López Obrador had swept to power, decrying the corruption of those who had preceded him during Mexico’s so-called “neoliberal age.” He took special aim at that era’s intellectuals as accomplices. Somewhat ironically, the president’s critique mirrored one made by Octavio Paz; that the intellectuals of the 20th century had too eagerly jumped into bed with the “Philanthropic Ogre,” a term Paz coined to describe how Mexico’s old regime dealt with the Mexican intelligentsia, alternately embracing and suffocating them according to its whims.

Hints of this system could be seen periodically, like when Carmen Aristegui lost her job after wondering out loud on live radio whether Felipe Calderón, Mexico’s president from 2006-12, was an alcoholic. More recently, the lavish spending on media by Enrique Peña Nieto, Mexico’s president from 2012-18, worked similarly, first in order to get elected (during his time as a state governor) and then to maintain a positive sheen on his presidency.

This last media splurge particularly irked López Obrador, who lost to Peña Nieto in the 2012 election. It very likely led López Obrador to showcase, early in his tenure, the receipts that he said proved the substantial funding that Mexico’s magazine intellectuals had received from government institutions. “And now he’s very angry,” said the president, referring to Krauze in front of a screen displaying the amounts paid to various publications during the previous administration, “because his magazine used to be subsidized by the government.” Figures like Krauze and Héctor Aguilar Camín (the head of Nexos) began to see their public profiles recede soon after. Letras Libres’ print runs declined, and while millions continue to read it, the publication no longer plays the same role in public discourse.

It felt like the dawning of a new era at the time, as the chattering classes debated who would fill the old guard’s shoes. But, as the years passed, it became apparent that nobody was managing to do so—at least not to the extent in which intellectuals had set the public agenda in the past.

“Talent hasn’t run dry after titans like Paz or Fuentes,” Consuelo Sáizar, an editor who has led many of Mexico’s great public and private cultural institutions, told me. “Though it is true that there has been talk about the crisis of the intellectual.”

López Obrador has benefited from belittling Mexico’s intellectuals, whom he sees as the closest thing to an opposition. The president has a limited list of who counts as a proper intellectual, though even his supporters are skeptical. “There are more intellectuals than the president believes there are, but far fewer than the opposition claims there to be,” Ezra Alcazar, chief of staff for the director of the Fondo de Cultura Económica (FCE), a cultural institution that receives government funding and is also Latin America’s largest publisher, told me.

Myriad reasons for the decline

So, what explains the paradox in which most agree there is no dearth of talent alongside an ongoing “crisis of the intellectual” in Mexico?

The most obvious cause is the rise of the internet, particularly its decentralizing effect on discourse, which has been seen everywhere, not just in Mexico. “The titans of old look smaller now because their voices have been diluted by social media,” said Yásnaya Aguilar Gil, a Mixe lingüist and prominent writer.

Success nowadays certainly seems to require more work. Denise Dresser—an academic, writer and political commentator—remains influential, regularly critiquing López Obrador (who frequently bites back), although her prominence seems more of an uphill struggle than in the early 2000s, when her role as a headliner on a now extinct radio program made her a more ubiquitous presence. Viri Ríos, who is one of contemporary Mexico’s larger intellectual personalities, comes from a new generation, and relies on a varied web of social media, newspaper columns, media appearances and international connections, including her network at Harvard, to build her public profile. But it is hard to escape the conclusion that fewer and fewer Mexican intellectuals are able in practice to build such a well-rounded presence across platforms, and thus attain the influence of previous generations, much less make a viable living doing so.

As the internet has taken over public discourse, the way in which users gained prominence took a turn towards the anti-intellectual. Social media algorithms encouraged and boosted intense emotion over nuanced dialogue. As traditional media was gradually supplanted by digital media, the old fashioned version of the intellectual was effectively deplatformed.

This of course is a global phenomenon. But what made the crisis deeper in Mexico was that the offline platforms that sustained public intellectuals were being simultaneously undermined by the Mexican government.

Paz’s Philanthropic Ogre system was done away with with relative equanimity. López Obrador’s administration cut funds not only from the old intellectual elites, but it gave few additional resources to intellectual endeavors favorable to the president. While local media has reported that hard news outlets like the left-leaning La Jornada have received massive increases in public funding, those that veer towards more highbrow, intellectual content have not. In fact, cuts extended not just to media subsidies, but also to universities and research institutions—other bastions of the Mexican intellectual. Meanwhile, even some pro-López Obrador magazines, such as Horizontal, have closed their doors. Their absence deprives even pro-government intellectuals of a platform for them to concentrate their debate and thinking on.

In large part, the reason for this is counterintuitive: López Obrador is a rather cultured man, who delights in quoting a variety of historical intellectuals at length. His early political mentor was the poet Carlos Pellicer. (Compare this to the previous president’s inability to name three of his favorite books at a book fair.) But this presidential intellectualism, combined with López Obrador’s penchant for centralization, makes it difficult even for new, uncorrupted, pro-government intellectuals to flourish.

The current environment is too poorly financed to keep any platforms afloat for long enough for anyone to gain much prominence, and it is tough to take root in the president’s shadow. Indeed, being a good obradorista often relies on toeing the line rather than rocking the boat with any kind of debate. The current climate of intellectual chill in Mexico is perhaps even more important than the dearth of financial resources.

Mexico’s new status quo has resulted in an anaemic version of its potential intellectual promise, and it couldn’t have come at a worse time. As the fate of the country’s democratic institutions hangs in the balance, now more than ever Mexico needs people to guide discussion away from everyday politicking and into the more serious territory of discussing in good faith the flaws and merits of institutions, like the National Electoral Institute (INE), and how best to reform them without burning the democratic house down. Everyone would benefit from proper, well-financed platforms to debate such questions—spaces which avoid the incestuous elitism and co-option by the powerful of yore but also eschew the baser instincts of the algorithm. It will ultimately require funding, something the new digital economy generally and the current Mexican government specifically are loath to cough up.

In this regard, Mexico—historically one of the world’s great producers of public intellectuals—has stumbled into the worst form of modern de-platforming at exactly the wrong moment in its history.

Listen to this episode and subscribe to the Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify, Google and other platofrms

—

González Ormerod is a Mexican editor, writer and historian. Currently the Latin America Editor at Rest of World, he has worked as editor-in-chief at Contxto and El Equilibrista and contributed to Contxto, Letras Libres, Literal Magazine and Nexos.