The removal of Nicolás Maduro marks a pivotal inflection point in U.S. foreign policy toward the Western Hemisphere. As articulated in the latest U.S. National Security Strategy, Washington is emphasizing the region as a core theater of competition, denying its extra-hemispheric rivals the ability to entrench economic, military, or political influence, and treating these issues as a matter directly tied to homeland security.

For nearly a quarter century, Venezuela served as a test case for how extra-hemispheric powers could exploit declining U.S. engagement to expand their footprint in the Americas. China, Russia, and Iran each employed distinct instruments—financial leverage, security cooperation, and ideological alignment—to entrench themselves in Venezuela’s political economy and project influence near U.S. borders. With Washington now engaging an interim authority led by Delcy Rodríguez, the U.S. faces the more difficult task of converting renewed hemispheric assertiveness into a durable realignment without causing prolonged instability.

Venezuela’s strategic importance makes this test unavoidable. It has the world’s largest oil reserves, emerging critical-mineral potential, and a legacy role as a platform for anti-U.S. influence in the region. Displacing extra-hemispheric rivals from this space has become central to Washington’s hemispheric strategy. Whether that objective can be achieved will depend less on dramatic gestures than on sequencing, incentives, and the careful reconstruction of economic and institutional foundations consistent with a strategy of denial rather than domination.

China: Financial leverage and oil capture

Among Venezuela’s external partners, China has been the most economically consequential. Since the early 2000s, Beijing extended more than $100 billion in credit to Caracas, largely through oil-backed lending tied to long-term energy supply. These arrangements bound Venezuelan production to Chinese repayment terms and embedded Chinese firms deeply in the country’s energy infrastructure.

This financial leverage translated into strategic access. Through joint ventures in the Orinoco Belt and long-term supply agreements, China secured preferential access to some of the world’s largest heavy crude reserves. Beijing’s approach was pragmatic rather than ideological; it focused on building infrastructure, technology transfer, and resource-backed finance to guarantee supply and hedge against instability in the Middle East. By the final years of Hugo Chávez’s rule, Venezuela had become a key node in China’s global energy diversification strategy.

Russia: Strategic signaling without economic rescue

Russia’s relationship with Venezuela has been defined less by economic depth than by military cooperation and strategic signaling toward Washington. Since the mid-2000s, Moscow has extended more than $20 billion in loans and credit facilities, primarily tied to arms sales and defense cooperation.

Following Chávez’s death, Russia preserved its military footprint but declined to provide meaningful economic relief as Venezuela’s economy collapsed. Between 2012 and 2020, GDP contracted by more than two-thirds, while hyperinflation peaked in 2018. Moscow’s engagement under Maduro focused on protecting sunk costs rather than underwriting recovery.

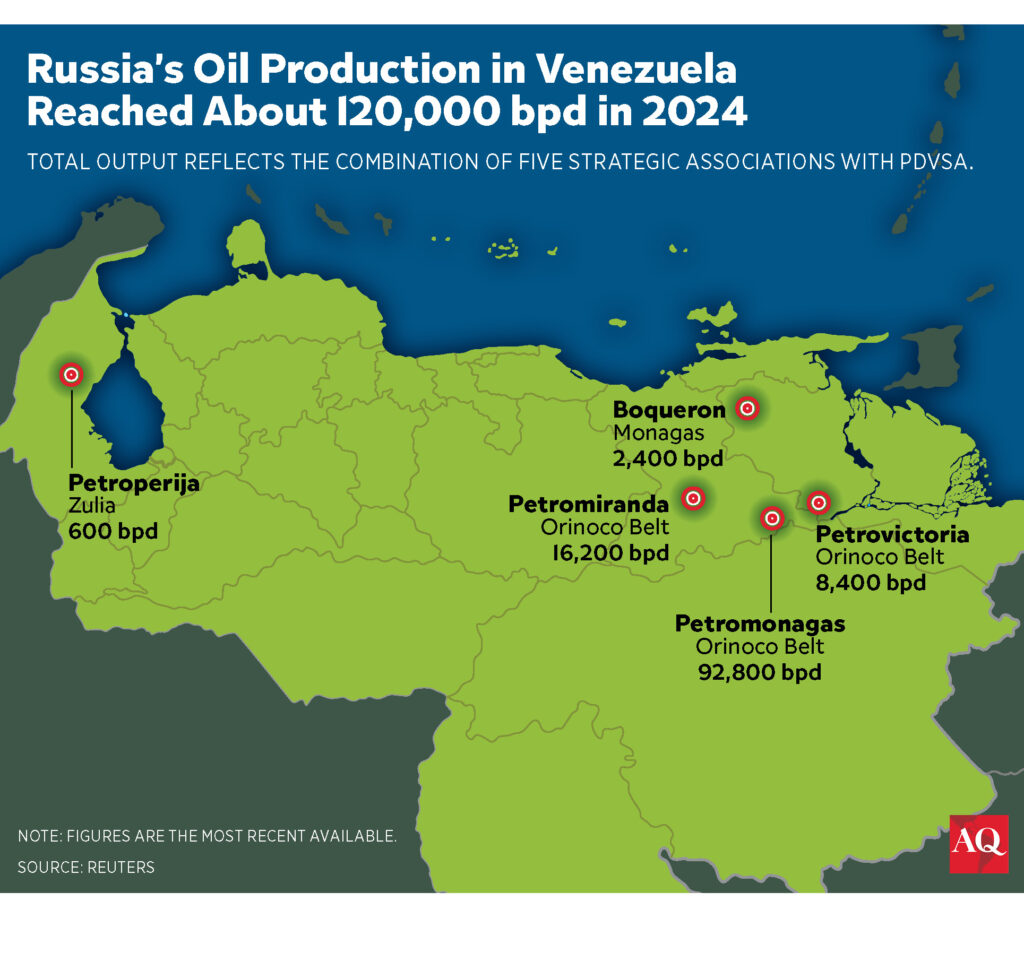

Russia maintained stakes in several oil projects and reinforced defense ties through arms transfers and military-industrial cooperation, but trade volumes remained modest, and no major new loans were forthcoming after 2018. Russia’s own fiscal constraints, exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, limited its ability to sustain Venezuela as anything more than a symbolic outpost.

Iran: Ideological alignment and sanctions evasion

Iran’s role in Venezuela has been narrower but symbolically potent. Bound by shared opposition to U.S. power, Tehran and Caracas cooperated on sanctions evasion, fuel swaps, logistics networks, and the use of shadow tanker fleets. Iran also supplied limited military technologies and technical assistance.

While Tehran lacks China’s financial scale or Russia’s military reach, its engagement amplified anti-U.S. narratives and demonstrated how sanctioned states can collaborate to blunt Western pressure. In doing so, Iran reinforced Venezuela’s function as part of a broader network of resistance to U.S.-led economic and political systems.

A managed recalibration

Displacing U.S. rivals from Venezuela will require sustained engagement—not only toward external partners but also toward regime-linked elites. Any U.S. effort will take place in the context of a regime that remains fragmented, coercive, and deeply criminalized; Venezuela’s post-Maduro transition is not occurring on a clean institutional slate.

Instead, it faces a system shaped by intra-elite rivalries, autonomous military interests, and entrenched patronage networks tied to oil, gold, narcotics, and informal coercive actors. Power struggles within this system will condition the pace and direction of any foreign policy recalibration.

These dynamics will complicate Washington’s ability to force extra-hemispheric actors out of Venezuela. So, Washington will likely rely on a calibrated mix of targeted sanctions, conditional sanctions relief, asset freezes, and international legal exposure to incentivize cooperation while deterring efforts to preserve Venezuela’s legacy arrangements with rival powers. This process is unlikely to take the form of dramatic expulsions or abrupt ruptures. More plausibly, it will unfold as a managed recalibration.

Economically, realignment will center on renegotiation rather than seizure. A post-Maduro government could seek to restructure sovereign debt, revise oil-backed repayment agreements, and re-bid energy and infrastructure contracts under new regulatory frameworks. Forced sales or asset seizures remain possible, but they would invite prolonged arbitration, capital flight, and reduced access to financing. Gradual recalibration, especially with China, offers a more viable path, preserving energy production while reducing strategic dependence.

Diplomatically, mass expulsions would impose reputational costs and risk escalation at precisely the moment when debt restructuring and energy normalization are most critical. Instead, Washington will press Caracas to downgrade relations, narrow diplomatic access, and recalibrate formal engagements in ways that limit influence without provoking open confrontation.

In the security and intelligence domains, foreign military and security footprints will likely be constrained more quickly, through access limitations, contract terminations, and the winding down of advisory roles. Intelligence cooperation, including with Cuba, is likely to be curtailed decisively.

Realignment over rupture

China, Russia, and Iran will not be passive actors. They “get a vote,” and their responses will shape the pace and character of any transition. Thus far, all three have emphasized sovereignty, contractual obligation, and non-interference, signaling that resistance will be pursued primarily through legal, economic, and diplomatic channels rather than force. None is likely to withdraw quietly, but neither are they well positioned to impose decisive countermeasures if a post-Maduro government prioritizes economic recovery and institutional normalization.

While Russian and Iranian influence may be comparatively easier to displace, China poses a more formidable challenge given the scale and depth of its investments.

If Washington moves decisively to unwind sanctions, ease its economic blockade, and engage meaningfully with Venezuela, it will have a credible opportunity to reset bilateral relations and marginalize extra-hemispheric actors. For this strategy to succeed, Rodríguez must demonstrate to internal regime rivals that rapprochement with the U.S. delivers tangible economic and political dividends. Conversely, prolonged hesitation would weaken her standing and create openings for internal and external actors opposed to the new arrangement. Ultimately, success will depend on Washington’s ability to move quickly and align the survival interests of transitional elites with economic recovery.