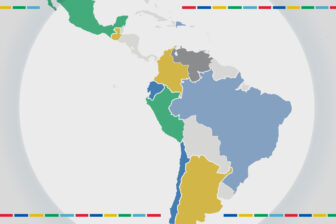

The whole controversy has a distinctly post-imperial feel to it: One by one, several governments in Latin America and the Caribbean are drawing a line in the sand, saying their presidents may not attend the Summit of the Americas next month unless the host, Washington, agrees to invite everybody—including the region’s dictatorships in Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela. But what feels to many like Latin American solidarity, or a golden opportunity to stick it in Uncle Sam’s eye, also tells a less flattering story about the region’s current political reality—namely, a wavering commitment to democracy.

To briefly recap how we got here: Biden administration officials have indicated the United States will only invite democratically elected leaders to the summit taking place in Los Angeles in early June. This feels to many in Latin America like a big step backwards, after Cuba was finally invited to a previous Summit of the Americas, hosted in Panama in 2015, following years of similar debates. Barack Obama famously shook Raúl Castro’s hand at that meeting; the universe did not implode. Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said this week he will not attend unless all countries are invited; several Caribbean leaders, and the presidents of Bolivia and Honduras have made similar statements.

So why is this happening again? One reason, of course, has to do with U.S. politics: The bloc of Latin Americans and their descendants in South Florida and elsewhere who saw their lives destroyed by the dictators in question, and would lash out at the ballot box if they were invited to an event on U.S. soil. It’s also true, though less commented, that since the heady days of 2015 when an opening felt possible, Cuba has repeatedly slapped away chances to liberalize, instead cracking down even further on its citizens. In March, it sentenced more than 100 people to jail terms of up to 30 years for participating in mostly peaceful protests over COVID-19 and food shortages in 2021. No one can seriously claim that momentum in Venezuela or Nicaragua is moving in the right direction either, or would be helped by inviting them to Los Angeles.

Even so, yes, this controversy probably could have been avoided. The Biden administration could have said six months ago: “OK, we’re inviting everybody, but we’re all going to look these dictators in the eye and tell them what we think.” Or, they could have clearly and publicly stated the opposite, and left countries such as Mexico and Honduras to make up their minds then. There has been an air of uncertainty around this summit from the beginning; some of that is the fault of the pandemic, and some is on the Biden team. There is also, frankly, a bigger debate about what these events are for—are they a reward for good behavior, an opportunity for countries with similar values to plan a better future, or a chance for dialogue about common challenges even among neighbors who strongly disagree? All options seem valid. But the U.S. does not “just” exclude dictators close to home from such meetings—it began excluding Russia from G8 events following its 2014 invasion of Crimea, an example that feels particularly poignant today for obvious reasons.

Philosophical questions aside, though, this does feel like a major moment in the relationship between the United States and its neighbors to the south. Many Latin American governments feel that Biden’s management of the guest list is an unwelcome attempt to turn back the clock to the 1990s or early 2000s, when Washington clearly sat at the head of the regional table. Those days are gone, of course. Latin American countries now have China as a partner and feel more empowered to defy the United States and try to occupy a middle ground between the two superpowers, as I recently wrote for Foreign Affairs. The summit itself was never going to be a game-changer in that dynamic—despite some last-minute efforts, Washington simply doesn’t have much new to offer on trade or investment. In other words, to many Latin Americans this feels like a perfect opportunity to say: No, it’s 2022, and we’re not going to take this unilateral nonsense from the United States ever again.

But there is also another, much less flattering trend visible here: A growing ambivalence toward democracy throughout much of the region. In a moment of clarity at a previous summit in 2001, all countries in the Western Hemisphere except Cuba signed the Inter-American Democratic Charter, affirming that “the peoples of the Americas have a right to democracy, and their governments have an obligation to promote and defend it.” This language has always been the grounds for Cuba’s exclusion from summits, and it was not an imposition from Washington—it was, rather, a full-throated rejection of dictatorship by elected leaders like Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Ricardo Lagos who fought, and risked their lives, for the return of democracy to their countries in the 1970s and 80s. But in the years since, the firm commitment of that generation of leaders has eroded, replaced by a kind of mealy-mouthed excuse-making for dictators who share the same ideological space, often disguised in the language of Latin American brotherhood. It is perfectly fair to ask whether López Obrador and others would be defending the right of the right-wing Argentine dictator Jorge Videla, or Chile’s Augusto Pinochet, to be present in Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, many elected Latin American leaders are themselves moving in a more authoritarian direction, warring with institutions and trying to concentrate power for themselves. They may therefore be keen to create an environment where democratic credentials are not a kind of “vaccine pass” to get into the club. Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro’s apparent decision to pull out of the summit, reported this week by Reuters, was not related to the Cuba question—but did come at a moment when he seems increasingly focused on undermining the October election in which polls show him losing, and the Biden administration is becoming more vocal in calling him on it.

At the time of publication, the White House did not seem to have fully closed the door on modifying the guest list. Similarly, some governments were leaving themselves a bit of room to change their minds. But regardless of how this story ends, it has provided a window into the state of the Americas today. It’s a new era; but one in which old trends, including some unwelcome ones, are back on center stage.