This article has been updated

SANTIAGO – Chilean politics have been a rollercoaster of late. Protests in mid-October, after President Sebastián Piñera announced a 4-cent increase in subway fares, quickly morphed into nationwide demonstrations. As the dust settled, and Piñera ceded to protesters’ demands, the country began to prepare for one of the most consequential debates of its recent history, over whether or not to draft a whole new constitution.

It was in this complex political environment that the coronavirus crisis emerged.

Suddenly, a government that lacked legitimacy with the public had to convince a mobilized population that it was prepared to deal with one of the gravest health care challenges of modern times.

For now, the embattled president has been given a reprieve from the discontent that threatened his government. Chileans have pulled together to confront the crisis, as most protesters quickly stood down and the public began abiding by social distancing recommendations. Even with over 5,000 confirmed cases, the country’s death toll remains relatively low.

But Piñera is not nearly out of the woods yet. If his government fails to protect low- and middle-income earners from economic hardship in the weeks and months to come, social unrest could again rear its head, and even be exacerbated by the crisis. Early on in the government’s coronavirus response, there are signs that Piñera’s political position is far from secure.

The reasons for this are two-fold. First, because the underlying causes of Chile’s unhappiness with its politicians and political institutions have not been resolved.

Prior to the outbreak, and despite party leaders’ conceding to hold a plebiscite on whether or not to write a new constitution, trust in public institutions had bottomed out. In the most heated days of the demonstrations, polls showed that just 5% of Chileans trusted Piñera’s government. The numbers were even lower for Congress (3%) and political parties (2%).

Piñera’s approval rating has since increased from 11% on March 6 to 21% today. But while social demonstrations have ground to a halt, it is almost certainly been out of fear of the virus – rather than satisfaction with the government’s response to unrest.

The deeper reason is that Piñera’s approach to dealing with the outbreak has pushed some of the same buttons that bothered Chileans in the first place.

Piñera’s political struggles seem to have colored his initial reaction to the crisis, including his apparent reluctance to call for an end to protests and a postponement of the plebiscite in the name of public health. Instead, the administration opted to tackle the pandemic by focusing mainly on sanitary measures, such as checking travelers arriving in the country, to try to contain the virus. But by mid-March, when it was no longer possible to detect the origin of some cases, the government strengthened its measures to contain the virus’ spread.

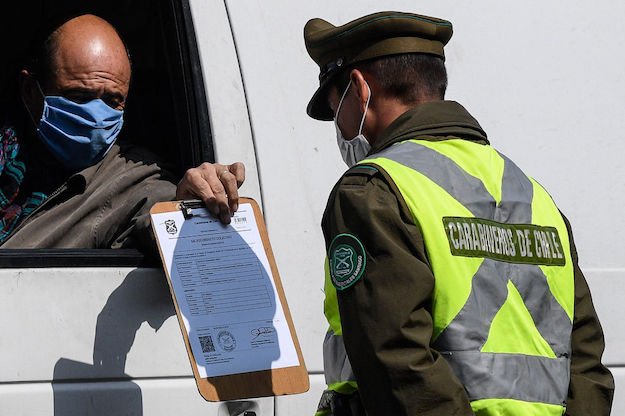

On March 18, Piñera adopted emergency measures for 90 days and closed Chile’s borders. In the following days, arguing that at-home quarantines were not being respected, the government adopted a nightly curfew and shut down theaters, gyms and shopping malls. Finally, the government implemented a lockdown for some high-incidence areas, set a maximum price for the coronavirus test at 25,000 pesos (about $29), and ordered the quarantine of everyone over 80 years old.

Most of those measures were well received, even if they were considered insufficient. But the government also announced some economic relief measures, such as a cash transfers for individuals without formal employment, the deferral of tax payments for businesses and a new law to regulate remote jobs.

The opposition has complained that these measures are mostly geared towards rescuing business, rather than protecting vulnerable households. Unions and opposition leaders recently denounced a labor department ruling that employers will not be obliged to pay salaries if work cannot be done because of quarantine or curfew.

On April 8, Piñera announced further steps, including measures to protect economic activities by guaranteeing higher liquidity to enterprises. He also announced the creation of a fund to protect the income of the most vulnerable, particularly informal workers. However, the use of the fund will be flexible, as the situation requires and depending on the context. Unfortunately, at least for the time being, the government will not provide a universal basic income to replace earnings lost due to the coronavirus emergency.

Initially, and true to form, Piñera and his health minister, Jaime Mañalich, decided to handle the crisis behind closed doors, with only the participation of a few, very close advisers. This lack of transparency led to strong criticism from two key actors who demanded to participate in the decision-making process: the Association of Physicians (Colegio Médico), and local mayors.

Izkia Siches, the head of the Colegio Médico, has been a prominent face since the start of the pandemic. She was instrumental in convincing political parties to postpone the April plebiscite on the new constitution to October. She has also denounced occasions in which health care protocols have not been followed, particularly because some regions of Chile performed fewer coronavirus tests than required by the Ministry of Health.

Mayors have similarly played a key role, pushing the government in its steps to close shopping malls and schools early on, even as Mañalich said he was not ready to consider such measures. They also confronted the government about its decision to avoid locking down the city of Santiago. One mayor went so far as to accuse the minister of health of hiding information about the number of deaths.

The virus has thus reinforced the narrative of the administration’s lack of transparency and the priority it places on supporting business. It has also allowed for a still sharper distinction between Piñera’s approach and that of the politicians and bureaucrats at local levels who have taken leading roles in responding to the crisis.

The result, for now, is a highly precarious political equilibrium. Around 43% approve of Piñera’s management of the coronavirus. But Siches and the country’s mayors fare far better (66% and 70% respectively), suggesting that many are still skeptical of the president’s leadership.

Two key factors will be critical in the months to come. First, a deterioration of economic conditions, without the government reinforcing effective safety nets to protect the most vulnerable, particularly informal workers, may well reignite social discontent, even if people are unable to protest on the street in large numbers.

Second, the risk of the health effects of the virus growing worse as Chile’s summer ends, and increases in seasonal flu and respiratory illnesses put additional strain on Chile’s hospital services. Siches and others have warned that existing medical equipment (including ventilators) and ICU beds may be insufficient if the virus spreads more widely. Rapid growth of the virus in that context will test Chile’s health care system, and the volatile social truce that the government is currently enjoying.

This article was updated following Piñera’s announcement of new coronavirus response measures on April 8

—

Castiglioni is associate professor of political science at Diego Portales University in Chile