This article is adapted from AQ’s print issue on reducing homicide in Latin America.

When Renato Roseno first visited Pirambu, one of Brazil’s biggest favelas, it consisted mostly of wooden shacks and dusty roads.

“Life was pretty precarious” in the early 1990s, he recalled. “People were battling for access to electricity and basic health care. The really big challenge was the high rate of infant mortality.”

Today, clusters of orderly two-story houses freshly painted in pastel blues, pinks and greens dot Pirambu and other areas of Fortaleza, a city of 2.6 million in northeastern Brazil. Almost all the roads are paved. Motorcycles, the status symbol of choice for much of the world’s emerging lower-middle class, whiz by constantly. Best of all, kids no longer die in such terrible numbers — over the past 25 years, the infant mortality rate in Brazil plummeted by two-thirds.

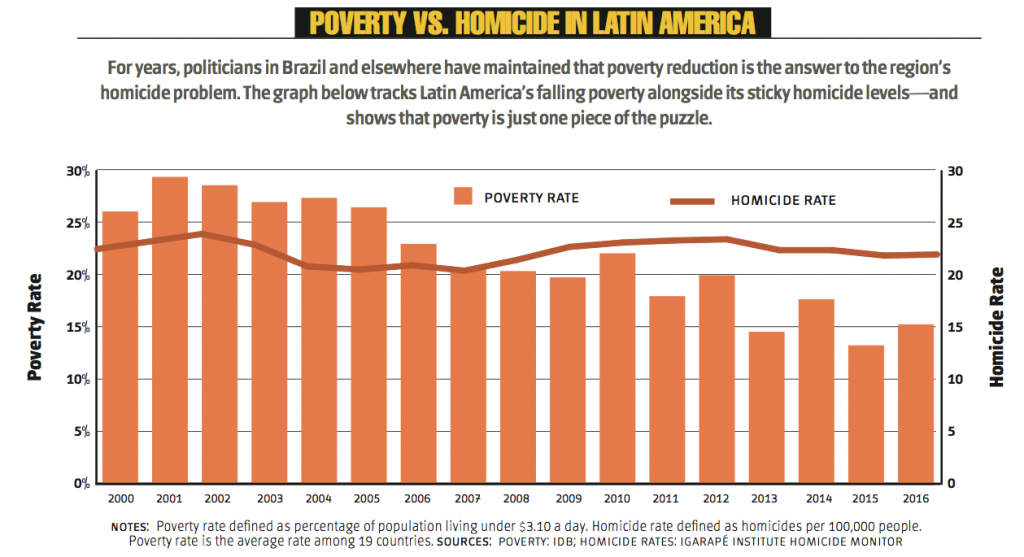

Yet this has exposed a new dilemma, one seen throughout much of Latin America: As prosperity has increased, so has violence.

The homicide rate in Ceará state, which includes Pirambu, has quadrupled since the late 1990s to more than 50 per 100,000 people. More than two teenagers per day die on average statewide, putting the death toll at 4,500 in just the last five years. Even though the northeast has enjoyed Brazil’s strongest economic growth, the previously calm region is now home to eight of the country’s 10 most violent states.

For Roseno and many other left-leaning politicians, this has come as a shock. “We have discovered that crime is about much more than poverty,” he said.

The 46-year-old Ceará state congressman spends his days trying to understand and solve the problem as the head of a legislative committee for tackling adolescent homicides. He has come to believe the keys include better community policing, education and programs that give teenagers an alternative to crime. But it’s an uphill battle. As violence soars, most voters these days say they want a hard-line approach, using shock troops instead of counselors and teachers.

In March, 50 percent of Brazilians told the pollster Ibope they agree with the statement “A good thief is a dead thief.” Many voters negatively associate softer law enforcement tactics with the 13 years of leftist government that ended in severe recession and scandal in 2016. Politicians have seized on this backlash; the leader in polls for this October’s presidential election is retired Army Captain Jair Bolsonaro, who has said he will give police “carte blanche” to kill suspected criminals.

In truth, criminologists these days have a good idea of what’s necessary to reduce homicide and other violence: a mix of preventive, data-based policing and smart social policy.

Roseno’s story illustrates how good people are out there trying to push such measures — but running into obstacles, including limited human resources, budget cuts and risks to their own well-being. “Society demands force,” he said. “Our approach is all about prevention. It has to be based on intelligence, a better city and a project for the future.”

“It’s Madness”

Born into a middle-class Fortaleza family — his parents owned a pharmacy — Roseno has been politically active in the Brazilian left since age 15. He first joined the Workers’ Party of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who oversaw the commodities-led boom of the 2000s that pulled some 35 million Brazilians out of poverty, most of them in the northeast. In 2005, unhappy about what he saw as the party’s unsavory political alliances, Roseno switched to a party further to the left: the Socialism and Liberty Party, or PSOL.

A fellow PSOL politician, Rio de Janeiro City Councilwoman Marielle Franco, was murdered in March in a still-unsolved crime that garnered international attention. Most believe she was killed because of her advocacy for victims of police violence. In 2017, Roseno was forced to employ bodyguards after receiving threats after a YouTube video of unknown origin alleged that he was close to gang leaders. A year later, he said he “still takes care” and “I never go to places on my own.”

Despite such risks, Roseno is energetic and constantly on the move — in a span of 24 hours in April he spoke with doctors and nurses at a local hospital, met with mayors from around the state, and gave an evening presentation to idealistic psychology students at the university. He seems constantly in campaign mode, occasionally sipping coffee but barely stopping to eat. He sees his wife, a journalist now studying in Brasília, only on weekends.

Back in the mid-1990s, Brazil’s drug-related violence was concentrated in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. More recently, homicides in those cities have fallen. But gangs with roots there, namely the First Command of the Capital (PCC) and the Red Command (CV), spread to other parts of Brazil. The presence of the CV in Pirambu is revealed by ubiquitous graffiti of its initials on street corners.

In 2018, the fever has continued to rise, with murders in Ceará up 22 percent in the first quarter compared to last year. As is typical around Latin America, most of the violence occurs in a relatively concentrated area: 17 of Fortaleza’s 119 neighborhoods saw 44 percent of the adolescent deaths that Roseno focuses on.

“The problem is that kids don’t see any future,” he said. “For the rest of society these kids are vagabundos. You have to give them opportunities.”

Lacking that, a culture of ultra-violence has set in. Members of rival gangs are often tortured and decapitated. Violence is celebrated in funk song lyrics and bloody deeds filmed and widely circulated on social media. WhatsApp, the Internet-based mobile phone app that is encrypted and thus hard to police, is a particular favorite of the gangs.

Roseno showed me images of a dismembered body, carefully reassembled, placed in a wheelbarrow and dumped outside a supermarket. “This guy messed up the words for his initiation rites into a gang and was barbarously tortured and killed,” he said. “It’s madness.”

Prevention Starts Young

It’s clear now that the economic growth of the 2000s and early 2010s solved old problems — but brought new ones. Migrants poured into the cities from poorer and more deprived rural areas, fragmenting families and social structures. Government services such as health care and education failed to keep pace. Roseno sees a missing civic element as well.

“We have seen increases in income but no accompanying improvement in the sense of citizenship, access to the public sphere and good public services,” he said. “This excessive consumerism has increased conflict.”

Some 60 percent of young murder victims had dropped out of school, Roseno said, so his committee lobbies politicians and legal officials to make attendance a higher priority. That pressure paid off in April when the state government introduced a program to monitor school attendance — a process not common in Brazil — and reward municipalities achieving the best results.

Roseno also works with a wide range of community activists. One is Evandro Rocha, a 44-year-old who served a long sentence for murder and now works as a mediator, encouraging kids in Pirambu not to follow in his footsteps. “When gang members threaten (each other), I say you are not going to do that here,” said Rocha. “The kids don’t (argue) because I’ve known them since they were little.”

Evandro Rocha

Evandro Rocha

In another area of Fortaleza called Bom Jardim, theater groups and musicians run workshops in a recently built community center, another government effort to create alternatives to the gangs. In the Palmeiras neighborhood, Paulinho, a former professional soccer player, has teamed up with World Vision, an evangelical Christian charity, to run an after-school club where children are taught civics alongside dribbling and heading skills.

Roseno’s efforts do enjoy some support in the state government. The dominant party, the moderate Democratic Workers Party, or PDT (whose leader, Ciro Gomes, is emerging as the left’s possible lead candidate in the October presidential election), backs them. Encouragingly, Ceará has an unusual history of successful social reform. In the 1990s, state and municipal efforts to reduce illiteracy and improve access to basic health care were the subject of American sociologist Judith Tendler’s influential book Good Government in the Tropics.

Nevertheless, amid Brazil’s enduring economic crisis, the Fortaleza legislature agreed to fund only about a sixth of the modest 60 million reais ($16 million) the committee requested in 2017 for a four-year prevention program. None of that money has yet been disbursed, Roseno said.

“When you ask them, the state legislators agree with the idea,” he said. “But there is a dissonance between what they say and what they do. There is a lack of urgency.”

Criminal Expansion

Geography also plays a role. Ceará and neighboring states are situated along the routes that link the coca-producing Andes to Atlantic sea routes and the expanding European market, making them ideal transshipment points for the export trade. Roseno said the fragile region is weakly resourced and thus more vulnerable to corruption than Brazil’s wealthier south. Long, thinly populated coastlines are also maddeningly difficult to police.

That social and geographical context is paralleled elsewhere, in particular in the lawless border areas of Mexico and Central America. Shifting alliances among gangs have complicated matters further. Besides the PCC and CV, two more groups — a local faction called the Guardians of the State and the Amazon-based Northern Brothers — are present in Fortaleza, for example. The breakdown of a truce among gangs led to a bitter fight for territory in 2016, and death rates spiked.

Children learn soccer and civics at an after-school program in Fortaleza

Children learn soccer and civics at an after-school program in Fortaleza

Meanwhile, drug gangs are extending their tentacles into more conventional criminal activities and corrupting state institutions. The gangs now make large amounts of money from the sale of weapons. Luiz Fábio Silva Paiva, a sociologist at the Federal University of Ceará, said the availability of heavy weaponry like assault rifles has become more pronounced since 2015.

They’ve also moved into the bank robbery business. Last year, gangs in Ceará bombed bank branches and security trucks on 70 occasions. Since 2015, gangs have slowly gained control of Ceará’s prisons. “The gangs use prisons as a recruiting ground,” said Silva Paiva.

In poor communities, the gangs’ riches, weapons and clothes give them huge influence, although it’s in the prisons and juvenile detention centers that connections become strongest.

“Outsiders tend to follow gangs like football supporters follow a team. It’s an identity thing. But inside, the links harden. As a prisoner you either join the gang or you become cannon fodder.”

With the October election coming, Roseno knows now is the time for building popular support for piecemeal reform and peacemaking — and that this will be a challenge. “Polarization is a danger. Our fear is that there will be a backlash,” he admitted. But he vowed to keep working in the same tireless, fearless fashion. “You have to have a lot of hope.”