The current situation cannot continue. The news of oil sinking to around $60 dollars per barrel, combined with Venezuela’s large fiscal deficit and deteriorating economy, makes the country’s annual $8 billion oil subsidy to PetroCaribe nations increasingly unsustainable. The question is, what will replace it.

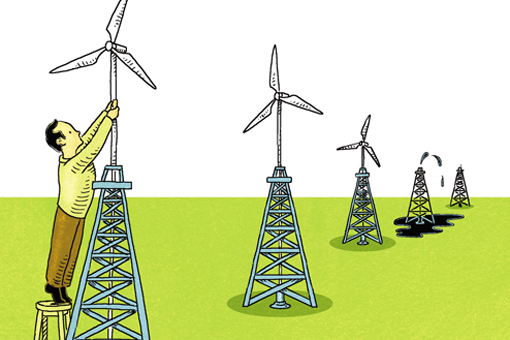

Fortunately, the 17 member countries of PetroCaribe don’t have to look far to find a viable alternative. Aruba’s successful energy policies have demonstrated that life without PetroCaribe is possible. Aruba’s government resisted the temptation to join PetroCaribe. Instead, it planned to achieve a zero-carbon footprint and energy independence—exclusively using renewable sources—by 2020, driven by public-private partnerships like those with Arizona State University (ASU) and BYD Company Ltd.

Aruba is using BYD green technologies to electrify public transportation and is transitioning its energy generation platform to incorporate wind and solar resources (for example, by doubling its wind farms and installing solar panels on school buildings). It is also making its energy storage systems more sustainable by updating the grid system and connecting it to the generation chain. As part of a sustainability education partnership, ASU held two professional workshops on systems design and installation of photovoltaic resources.

Small-scale liquified natural gas (LNG) plants or low-sulfur coal could also be viable alternatives. But Aruba’s solar and wind-based model provides the Caribbean with the most sustainable long-term energy platform capable of replacing PetroCaribe.

The good news for Aruba is that by foregoing Venezuelan patronage, the country has established the foundation for sustainable long-term growth. Meanwhile, for PetroCaribe members the incentives for developing sustainable alternatives have been depressed by Bolivarian largesse.

But renewable energy—while important—can’t provide the full answer for countries post-PetroCaribe, especially in the short term. Fully exploiting renewable energy sources will require restructuring the current model of regional cooperation. That, in turn, will require the involvement of North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) member states—Canada, the U.S. and Mexico—and their engagement in providing access to more sustainable energy sources.

Beyond the sheer fiscal irresponsibility of PetroCaribe as an enterprise, economic pressures are mounting for Venezuela to curtail its shipments to the Caribbean. Venezuelan oil production has fallen, and a series of loan deals between China and Venezuela at very favorable terms to China has meant that Venezuela has to divert an increasing share of its petroleum exports to China to pay its debts.

The flip side of the coin is equally troubling. The cost of PetroCaribe’s petroleum imports represents, according to the Royal Bank of Canada, on average between 7 and 12 percent of the participating countries’ GDPs. Yet in spite of this massive subsidy, economic growth in the Caribbean remains fragile. All the participating countries, except Suriname, are running a balance of payments deficit, despite only having to make a percentage of the payment up front (about 50 percent of the cost when oil prices are between $51 and $100 per barrel)—the balance being payable as a loan with 25 years maturity at 1 percent interest per year, provided oil prices are above $40 per barrel. Some even have the privilege of being able to pay off the loan with products instead of cash.

As of 2012, the principal debtors are the Dominican Republic ($11 billion), Jamaica ($7 billion) and the Bahamas ($3 billion). Together with Nicaragua, they represent the bulk of the $12 billion owed by PetroCaribe members—which Venezuela is unlikely to recover for decades. Indeed, Venezuela recently sold part of its Dominican Republic

PetroCaribe debt to Goldman Sachs at a 60 percent discount.

Not only have these countries staved off economic crisis by becoming addicted to cheap oil, they have dug themselves into a credit hole. The question of what will happen when Venezuela pulls the plug and the entire system collapses has become a regional concern.

The answer may lie to the west and north. Since the start of PetroCaribe, the U.S. has become a net energy exporter. Canada has increased production, and Mexico is expected to follow suit following recent energy reforms. With the uptick in production, the NAFTA states have a unique opportunity to revamp the hemisphere’s energy production and supply chains. Indeed, U.S. Vice President Joe Biden announced this year the Caribbean Energy Security Initiative involving a portfolio of programs to help transform the electricity sector.

The first step of a potential new cooperation plan involving regional energy-exporting countries would be to move beneficiary nations out of PetroCaribe’s unsustainable and risky subsidy system. A more rational model would resemble the San José Agreement, the 1980 precursor to PetroCaribe. Under that arrangement, discounted or subsidized Venezuelan oil exports required the beneficiary countries to import engineering services from Venezuelan companies to build infrastructure, or to purchase Venezuelan manufactured goods. In an updated model, energy savings from the discounted or subsidized oil would be invested in joint ventures with the private sector from the cooperating countries (Venezuela and the recipient) to develop alternative energy sources and infrastructure.

The second step is two-pronged. To resolve its financial problem, Venezuela would have to almost entirely refinance the debt accumulated by PetroCaribe beneficiaries. That would mean exploring available alternative energy sources. One option is to build power plants fueled by LNG, by ethane or propane gas from the U.S., or by low-sulfur Colombian coal. Trinidad and Tobago has plentiful gas resources and an LNG plant that sends some supplies to Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, but scaling this up requires pipelines, which—in addition to representing a huge financial commitment—do not facilitate a bridge to renewable energy platforms. The kind of small-scale LNG plants pursued in Jamaica may be a better answer in terms of alternative but non-renewable energy sources.

With sustainable cooperation, Caribbean nations can not only free themselves from oil dependence, but also escape the subsidy-and-debt cycle that PetroCaribe created. By cushioning the blow of the collapse of easy, cheap oil, NAFTA countries can help lay the groundwork and incentives for the construction of a more sustainable, healthy renewable energy system in the Caribbean.