This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on millennials in politics

Editor’s note: Henrique Vieira was elected as a federal deputy for Rio de Janeiro state on October 2.

RIO DE JANEIRO – To roaring applause, Baptist pastor Henrique Vieira took to the small stage in a bar in Rio de Janeiro’s historic port district, where enslaved Africans were once traded in an open-air market. He wore a sticker that read “Jesus is Black” and spoke softly into the microphone.

“My dream is not an evangelical country,” Vieira told a crowd of a few dozen people. “I don’t want the state to be an extension of the church. I want a country that is united, fair and where children aren’t going hungry.”

It was an unusual opening for an evangelical pastor seeking to win over voters. But it is exactly this brand of politics—anchored in social and racial justice—that has made Vieira, 35, a wildly popular figure on the Brazilian left.

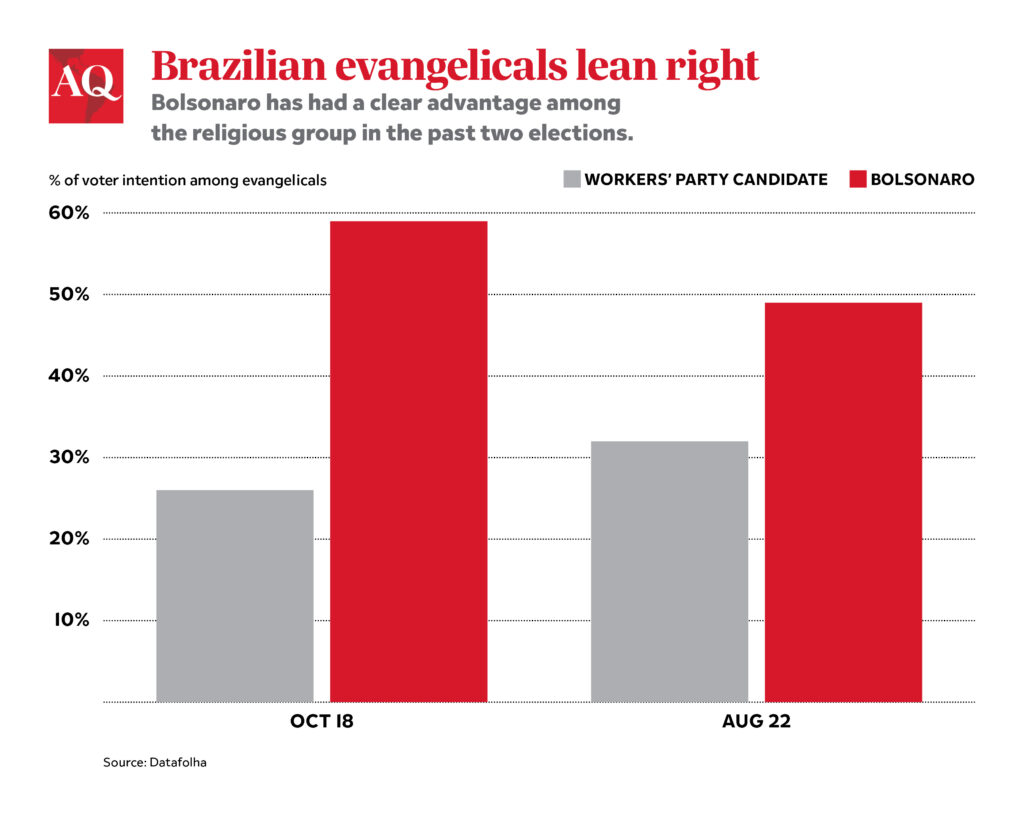

Now, Vieira is running for a seat in Brazil’s Congress—making him a test case in a country where 70% of evangelical Christians voted for President Jair Bolsonaro in 2018. As the evangelical community continues to grow here and elsewhere around Latin America, Vieira’s campaign may help illustrate whether the region’s politics will inevitably become more socially conservative—or whether another, more progressive path is also possible.

Vieira, who grew up across the bay from Rio in Niterói, told AQ he sees no contradiction between his faith and his brand of politics. “The gospel is what gave me the force to fight inequality, to fight racial injustice,” he said. “My religion is the root of my activism.”

This is not the first time that Vieira has dabbled in politics. Between 2012 and 2016, he was a city councilor in Niterói, pursuing a leftist agenda focused on the poor. Vieira has now set his sights on federal politics, running for a seat in Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies under the banner of the leftist PSOL party.

Evangelical pastors are not a rarity in Brazilian politics—but Vieira’s path to politics has in fact been uncommon. A trained actor and clown artist, he’s a familiar face in Brazil, thanks to a role in Wagner Moura’s blockbuster film Marighella (2019) and a musical collaboration with popular rapper Emicida.

Vieira’s decision to run for office, he told me, was fueled by the rise of religious fundamentalism. Increasingly, he sees religion being used as a tool by the far right, spearheaded by Bolsonaro, who is seeking a second term in October’s elections.

“It is very important that the left can counter fundamentalism,” he said. “I understand that faith and politics are related. But faith cannot be a power-grabbing instrument. … That is dangerous, it is undemocratic.”

The left searches for allies

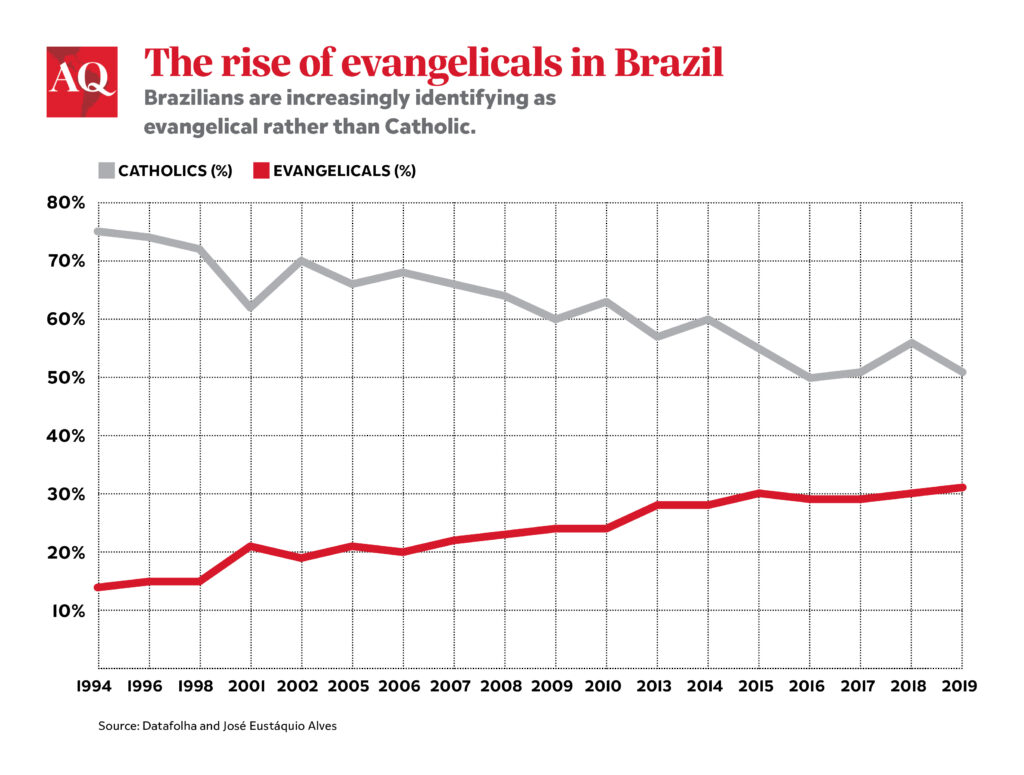

His candidacy is part of a broader attempt by the Brazilian left to win over the country’s growing evangelical voter base. While about half of Brazilians still identify as Roman Catholic, evangelicals now make up about 30% of the population, doubling their share in just two decades. This echoes a trend across Latin America, where about a fifth of the population now identifies as evangelical, up from just 4% in the 1970s.

Evangelicals are expected to become a majority in Brazil within the next decade, said Victor Araújo, a political scientist and the author of a book on the politics of Brazilian evangelicals. And winning over this influential voter base is perhaps the biggest challenge facing the Brazilian left.

“Once these voters become the majority, then it’s going to be really hard for the left to have a dialogue with them,” Araújo said. “It will become much more difficult for the left to win elections … so it is turning to churches and searching for allies.”

Vieira is a powerful ally for the left. His sermons about racial justice and religious tolerance attract hundreds in Rio and Niterói. He’s a popular wedding minister too, sought after by straight and gay couples alike. And Vieira’s appeal goes beyond the church: On social media, his activism has helped him amass more than half a million followers.

Yet while this has made Vieira a strong contender for a seat in Congress, experts question whether other moderate evangelicals can draw popular support on a similar scale. “Henrique is an important, emblematic example,” said Ana Carolina Evangelista, executive director at the Institute of Religious Studies, a think tank. “Is it possible to be evangelical and progressive? Definitely—just look at him. Is he likely to draw more votes than a (religious) candidate on the right? Probably not.”

There are 640 candidates running under religious banners this year, including 474 pastors. Candidacies from evangelical leaders jumped 17% compared to 2018, data from Brazil’s electoral court shows. But most of these candidates fall on the political right, Evangelista said.

In a way, this reflects the electorate that such candidates are courting. Some 60% of evangelicals identify as Pentecostals, embracing deeply conservative views that often clash with progressive leftist policies on issues like abortion or transgender rights.

This ideological division has been fed by influential ultra-conservative pastors like Silas Malafaia and Marco Feliciano—a congressman since 2011— who have aggressively criticized the left, casting it as a major threat to Christian values and urging their congregations to reject progressive candidates like Vieira.

In 2018, the political power of the evangelical church became crystal-clear: Some 70% of evangelicals voted for Bolsonaro, whose rhetoric about a leftist attack on “traditional family values” won him the loyalty of Brazil’s most influential evangelical pastors, who mobilized their congregations to vote for the then-candidate.

In the four years since Bolsonaro’s 2018 election, the president’s popularity has tumbled—among evangelicals and non-evangelicals alike—partially thanks to a botched handling of the pandemic and a painful economic crisis that has left many Brazilians hungry and unemployed.

Vieira has urged his own followers to reject Bolsonaro. During the pandemic, Vieira sharply criticized the president’s advice against masks and social distancing. “Bolsonaro has shown himself to be truly genocidal,” he wrote on Facebook early in the crisis. As elections drew closer, Vieira argued that “toppling Bolsonaro is an act of love.”

Faced with dwindling support, Bolsonaro has responded by doubling down on divisive “culture wars.” And his strategy may have helped him recover his advantage over his rival, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

“It’s the economy…”

“The typical evangelical in Brazil is a low-income, Black woman living in a neglected neighborhood,” said Evangelista. “These people are also worried about jobs, about education, about income inequality. And these are issues that can help the left connect with them.”

Lula’s PT was once the party of choice for many of the poor, Black Brazilians that now fill evangelical churches across the country. But the left’s shine wore off as an economic crisis battered Brazil and a sprawling corruption scandal embroiled PT’s upper echelons, including Lula himself. And in tough times, evangelical churches swooped in to help the needy, rescuing drug addicts, running after-school programs and training the jobless.

“The left has lost touch with this base,” said Juliano Spyer, an anthropologist who studies evangelical movements. “Now, we see churches doing things that improve the lives of people.”

As a result, evangelical churches have amassed tremendous sway in such communities, oftentimes giving religious leaders the power to shape the voting patterns of their congregations, Spyer noted. “While the state remains absent from poor communities until election time, the church is there every day,” he said. “Church leaders end up gaining the trust of the people.”

This is evident in Vieira’s own church. During the pandemic, it handed out food parcels to the needy and educated followers on how to avoid COVID-19. These days, it is also fundraising to prepare high school students in poor neighborhoods for college entrance exams.

Building alliances with leaders like Vieira may be helping the Brazilian left attract more moderate evangelicals. But as leftist parties seek to elect candidates, they may end up shifting away from issues that could cost them votes among more conservative evangelicals.

“Parties want to win elections,” Araújo noted. “The left also has to play the game at election time. And they will adapt to voter demands, so they can get candidates elected.”

Vieira, meanwhile, has not shied away from such talking points. In fact, his religious beliefs are right in line with his leftist agenda, he insisted. “Evangelical values are all about social justice and human rights. Whether we call them leftist, or not.”

—

Ionova is a journalist based in Rio de Janeiro