This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the Trump Doctrine

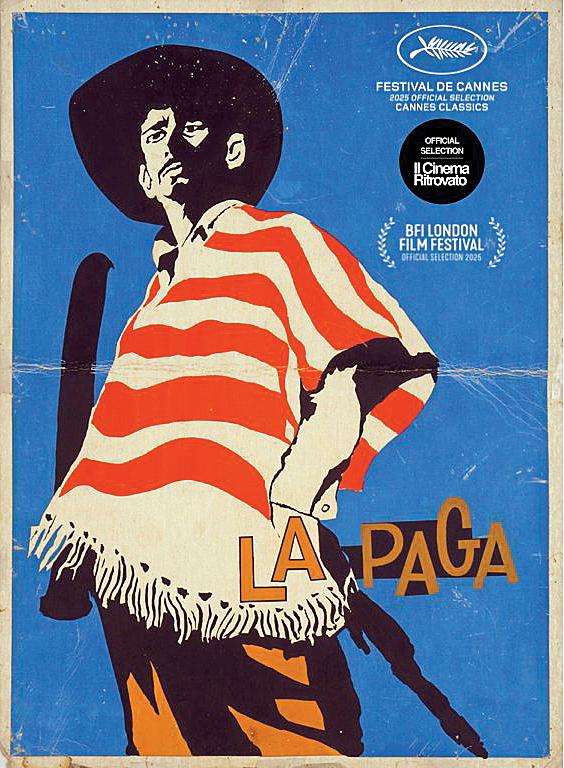

Last year, for the first time since 1962, moviegoers around the world got to watch Colombian director Ciro Durán’s La paga. The film was believed lost for decades, until Durán’s children discovered a forgotten copy in Venezuela’s national cinematheque. For most of his career, Durán earned acclaim for his incisive documentaries on a range of social problems, from youth homelessness to deficiencies in public transport. The rediscovery of La paga, his first feature film, shows Durán in a new light, capable of creating a fictional world full of poetic notes that still reflects his politics.

Set in the Andes, La paga portrays a deceptively simple tale: A poor peasant awaits his meager wages so he may pay for his sick son’s medical treatment and assuage his pregnant wife’s fears. Through its formal construction—particularly its soundscape, editing, and mise-en-scène—Durán’s film marries politics with poetry, elevating his nameless protagonist to a proxy for all working-class people and their struggles. In this sense, La paga laid the groundwork for several major movements in Latin American cinema.

Beyond the opening credits and very first scene, when a shepherd’s horn announces the start of the workday, no music (on-site or off) accompanies the actions that unfold throughout the film. The smallest of sounds are thus amplified—for instance, footsteps as shoeless peasants walk along a dirt road on their way to large swathes of farmland. Silence brings intimacy and immediacy to each shot. It also accentuates the little dialogue that does emerge. When the foreman yells, “Don’t fall asleep, dammit. Stop being lazy!” to his overworked and impoverished peons, his voice thunders.

La paga

Directed by Ciro Durán

Screenplay by Ciro Durán

Distributed by Maleza Cine

Colombia and Venezuela

The film’s montage strengthens this sense of immersion. Durán stretches out his scenes, allowing us to inhabit the peasants’ laborious tasks. Two men till a crop with the help of a cow over the course of a meticulously teased-out sequence. We first see the trio from a wide shot. Close-ups of the farmers’ upper bodies come next, followed by shots of their moving feet. In the process, Durán realistically captures the rhythm of time through a tiring workday.

These techniques reach a crescendo when the protagonist runs into trouble with the police. During his time off, he gets drunk to vent his frustration with his precarity. In jail for public intoxication, he dreams of standing up against the land-owning class in town. Three columns of armed peasants dressed in white advance. As they move forward, men in black suits—that is, the wealthy—take choreographed steps backward. The confrontation is arranged almost like a high-stakes ballet. In a recent interview, Durán’s son observed that the incarcerated peasant rebels only in his imagination. His political impotence remains inversely proportional to the richness of his fantasies.

Durán was in his early 20s when he made La paga. He had left his native Colombia for booming Venezuela a few years before to make money. In the early 1960s, during Rómulo Betancourt’s second term as president, the government censored his film. Durán himself was imprisoned for a year, on account of his pro-communist activity. Inspired by the Cuban Revolution, guerrilla groups had been fighting against Betancourt’s administration for years. As part of the official campaign to quell these forces, far-left leanings were not tolerated in any sphere of life.

La paga reflects the injustice at the core of Venezuela’s standoff between democracy and insurgency in the 1960s: namely, the enormous gulf between the haves and the have-nots. Perhaps ironically, Durán actually had his native Colombia in mind when he directed the film, even though he collaborated with a Venezuelan cast and crew. The two neighboring countries, often at odds with one another, are similar in many ways. More than 60 years later, La paga captures a reality that still exists in Colombia and Venezuela, as both nations remain stubbornly riddled with inequality. By privileging art over violence or propaganda, Durán shaped a deeply affecting portrait of human misery and dignity.