Growing ties between Brazil and China were a reality well before Donald Trump came into office. But as the U.S. president tries to intervene in Brazil’s judiciary and politics and imposes one of the highest tariffs in the world, enthusiasm for collaboration between the two governments seems to be at an all-time high.

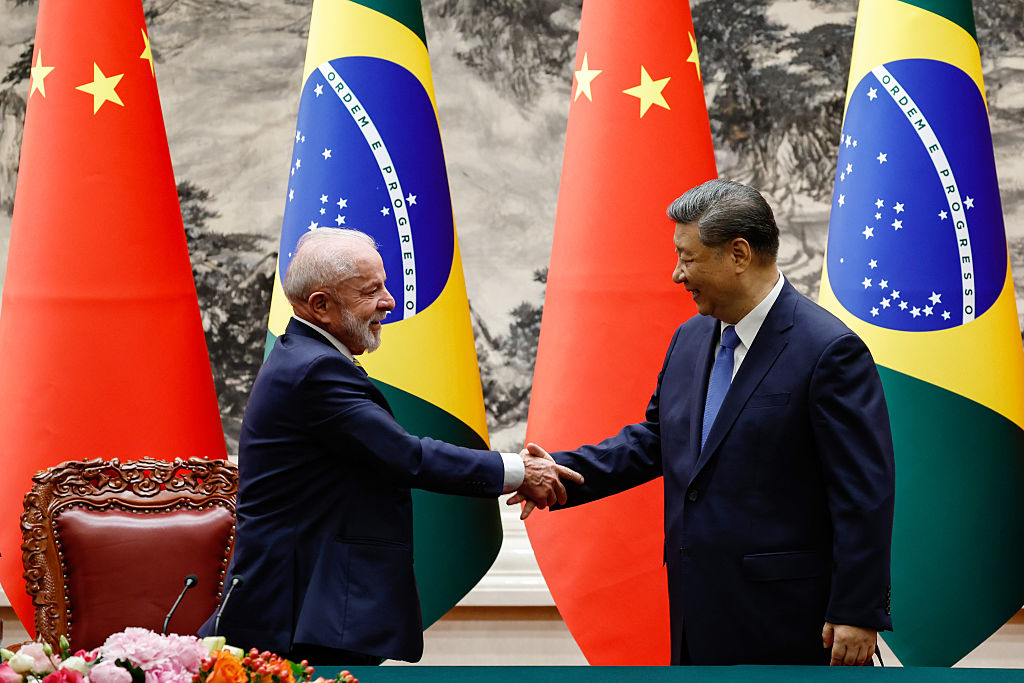

“Our ties are at their best moment in history,” China’s President Xi Jinping said last week after holding an hour-long call with President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. “China supports the Brazilian people in defending their national sovereignty and supports Brazil in safeguarding its legitimate rights and interests,” he added. Xi also told Lula that China “stands ready to work with Brazil to set an example of unity and self-reliance among major countries in the Global South.”

China has been a pivotal commercial partner for South America, and the tie with Brazil has for years been the strongest—it’s China’s top trade partner in the region and one of its main foreign investment destinations. In recent years the breadth of the relationship widened, even under former President Jair Bolsonaro, who used anti-China rhetoric and wanted to see Brazil more aligned with the U.S. During Lula’s third term, the connection has strengthened further.

2025 has seen significant developments. In July, Brazil hosted the 17th BRICS summit, and Brazil and China announced the construction of a bi-oceanic railway corridor between Brazil and Peru’s Pacific coast. Chinese car maker BYD also rolled out the first electric car built entirely in Brazil, at its new factory in Camaçari, Bahia, its first outside Asia.

As a symbol of that evolving bond, Brazil’s diplomatic mission in Beijing is looking for a new and bigger home and adding more personnel as well. For the first time, the embassy in Beijing will have an army general and a rear admiral—only Brazil’s embassy in Washington has that level of military seniority.

“Brazil will resolve many of its trade issues by selling more to China and China will also benefit”, said Hussein Kalout, international advisory board member at the Brazilian Center for International Relations (CEBRI).

The strong relationship does have nuances, however, and Brazil is not looking to put all its eggs in China’s basket. For Brazil, the moment seems right to accelerate its longstanding diplomatic policy of diversifying its partners and strengthening ties with other Global South countries. Vice President Geraldo Alckmin will visit Mexico at the end of the month, along with at least 113 companies, to meet with President Claudia Sheinbaum about expanding commercial ties. This week, President Lula called France’s Emmanuel Macron to try to move the EU-Mercosul deal. In March, Brazil and Vietnam signed an agreement to collaborate more on areas ranging from defense and the economy to cultural cooperation.

“Diversifying our market is key. If these tariffs had been imposed 25 years ago it would have been a disaster. Today, they are uncomfortable and we must take measures, but we must continue this diversification (…) with BRICS countries and others, too,” said Celso Amorim, Lula’s top foreign policy adviser, on the Brazilian interview program Roda Viva. He also recently told the Financial Times that Brazil is looking to deepen ties with BRICS nations and others to avoid relying on one single country.

Economic ties

In the context of the U.S.-China rivalry, Washington is anxious. According to U.S. media, Brazil’s hosting the BRICS meeting was a factor in the Trump administration’s imposition of tariffs. On the other side of U.S. politics, Senate Democrats recently wrote a letter to the president saying “a trade war with Brazil would make life more expensive for Americans, harm both the American and Brazilian economies, and drive Brazil closer to China.”

China has been Brazil’s main trading partner since 2009, when it overtook the U.S. It is the world’s biggest soybean importer, and gets most of its supply from Brazil. In 2024, 28% of Brazil’s exports went to China. In 2023, Brazil was China’s main supplier of soy, beef, cellulose, corn, sugar and poultry.

The balance of trade has historically been favorable to Brazil, although China has increased its exports in recent years. And when the U.S. tariffs came into effect, China authorized 183 new Brazilian coffee companies to sell to its market, and did the same with other products.

A recent new step is negotiation for the adoption of mechanisms to track the origin of agricultural products, particularly soy and beef. The goal is to create a system where both countries recognize the same environmental certifications, so that products can be tagged, for example, as “carbon-neutral beef.” There’s also talk of China importing Brazilian ethanol for the production of “sustainable aviation fuels.”

A common criticism of the dynamic between the two countries is that Brazil is merely an exporter of raw materials and an importer of more sophisticated goods, which would be damaging to Brazil’s economy in the long run. Lula is aware of this danger, and has said he doesn’t want Brazil to focus on soy and iron exports only.

Commodities indeed comprise the overwhelming majority of exports, but the trade relationship is no longer based solely on them. The manufacturing industry represented 23% of Brazil’s exports to China in the first quarter of 2025, an increase of 6 percentage points compared to the same period in 2024, according to a report from the Brazil-China Business Council.

The kinds of exchanges are changing, too, from government to government, to company to company, to company to client. Beyond BYD’s new factory in Camaçari, expected to be fully functional by the end of 2026, green energy and telecommunications services are seeing strong Chinese investment, and Chinese companies operating in fields like delivery apps are expected to be active in Brazil in the coming years. Some worry that the benefits could be uneven. “We’re not really talking about tech transfer in these cases, we’re talking about building infrastructure like factories in Brazil to be able to sell goods in the Brazilian market and others that are easily accessible from Brazil,” said Margaret Myers, director of the Asia & Latin America Program at the Inter-American Dialogue.

The balance of trade is also changing in recent years, with Brazil importing more from China: 26% of imports now come from China, and 6% of cars in Brazil are now Chinese. Almost all of what is imported are manufactured goods like oil rig platforms, solar panels or memory cards. While the predominantly right-wing agricultural sector seems more than satisfied with the relationship, industry is less so. In 2024, Brazil’s industry ministry launched a number of investigations into alleged dumping of a range of industrial products by China, from metal sheets and pre-painted steel to chemicals and tires.

A relationship that will endure

Brazil’s commercial relations with China go back to the late 1990s, and have endured regardless of who has been in power, whether right or left.

Unlike the U.S., which supported the overthrow of the democratically elected government of João Goulart during the Cold War, China does not have a history of intervening in Brazilian politics. A recent poll indicated that a majority of Brazilians have a positive view of China. Many Brazilians, however, also see Beijing as authoritarian and repressive toward minorities, and are aware of its controversial investments in Africa, for example. Polls also indicate Brazilians would rather have the U.S. than China as a commercial partner. However, unlike the U.S., China rarely adopts a moralizing tone, argues Kalout—and Brazilian leaders often believe they can have a more pragmatic relationship with Beijing. China offers predictability, reliability and does not come off as aggressive.

Ultimately, the material ties are now quite deep.

While in office, former President Jair Bolsonaro, a Trump ally, adopted a hostile posture toward China. In 2018, Bolsonaro became the first presidential candidate to visit Taiwan since Brazil recognized China in the early 1970s. During his 2018 campaign, Bolsonaro portrayed China as a predatory economic power, famously saying that Beijing is not just “buying in Brazil—it is buying Brazil.” Early in the pandemic, his son Eduardo spoke of the “China virus.”

But economic reality kicked in, and Bolsonaro was criticized for his attitude toward China even by his allies. Brazil’s agricultural sector is a big winner in the trade relationship, and it is heavily right-wing. Agribusiness is well-represented in Congress, and the legislative wields considerable power over the executive branch. “Today, no president can decouple from China. It’s not a viable option for anyone,” Kalout has said.