GUATEMALA CITY — When President Alejandro Giammattei announced on May 16 that Consuelo Porras would serve another term as Guatemala’s attorney general, the U.S. response was striking in its certainty. The State Department quickly condemned her selection, saying that Porras was “involved in significant corruption” and that she had repeatedly obstructed anti-corruption investigations “to protect her political allies and gain undue political favor.”

The European Union also raised concerns, but it is the response among the general public in Guatemala that says most about where the country has been and where it’s headed. Behind caustic headlines lies a momentous change in public attitudes, with the potential to reorient the country’s politics. Guatemalans are paying attention to the ups and downs of their country’s institutions like never before—and making clear that they won’t stand for politicians who fail to take corruption seriously.

The attorney general selection process has been a case in point.

“People were following it like a telenovela,” Marielos Fuentes, the head of Guatemala Visible, a nonprofit organization that live-streamed the proceedings, told AQ.

And in the context of this heightened public interest, Giammattei’s decision to give Porras another term has raised tensions dramatically, said Jordán Rodas Andrade, Guatemala’s Human Rights Ombudsman. “It’s a situation set up for an explosion,” he told AQ. “Guatemala is a pressure cooker right now and the government is wearing out people’s patience.”

This tension around Porras’ selection reflects a change in public consciousness that has been a decade in the making.

When Guatemala signed its Peace Accords in 1996, its institutions had been weakened and warped by 36 years of armed conflict, many of them under U.S.-backed dictatorships. And yet in 2013, Guatemala became the first country in history to convict its own former head of state—Efraín Ríos Montt—for acts of genocide. Two years later, then-Attorney General Thelma Aldana worked with a UN- and U.S.-backed anti-corruption commission, the CICIG, on a groundbreaking investigation that sent shockwaves through the country. They proved that the sitting president, Otto Pérez Molina, and his allies had stolen millions of dollars from public coffers. Pérez Molina went from the presidential palace to prison, and dozens more of the most powerful people in the country were jailed.

But before long, Aldana was forced into exile and the CICIG was dismantled. In 2018, President Jimmy Morales expelled the CICIG—a move met with silence from the Trump administration—and selected Porras as attorney general. The Morales and Giammattei administrations have largely undone the institutional legacy of the war crimes and corruption prosecutions of the last 10 years. The social legacy of those cases, however, remains intact.

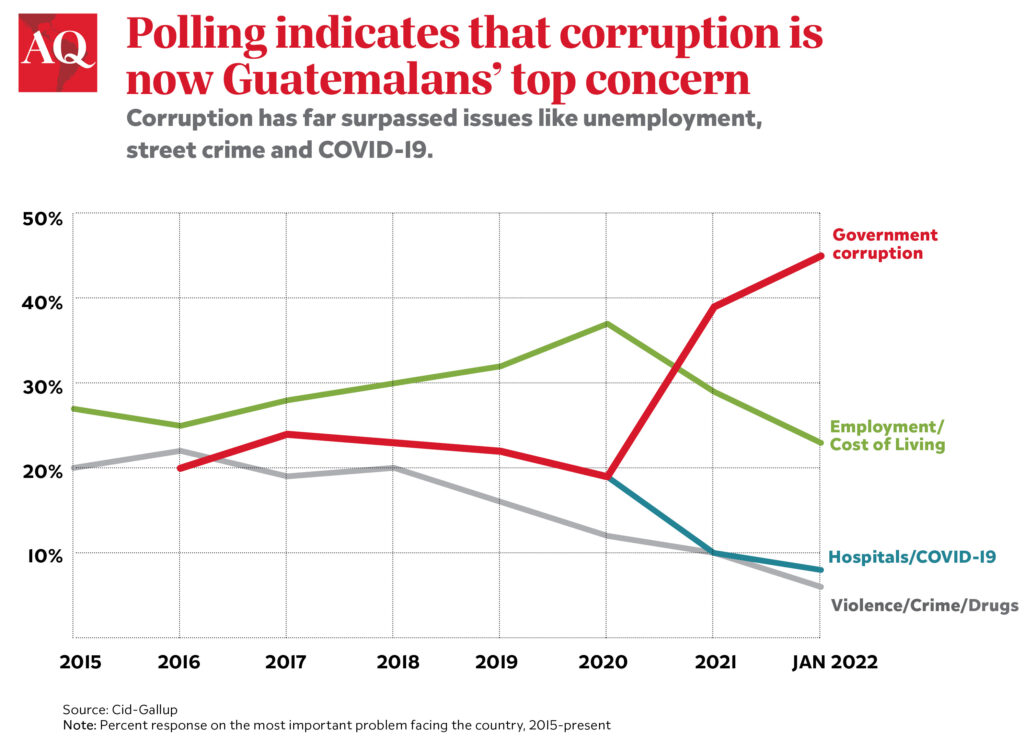

Indeed, Guatemalan public opinion has shifted dramatically in the last decade, said Luis Roberto Haug of Cid-Gallup, which has conducted polling in the country since 1982. Guatemalans now say corruption is the biggest problem facing the country, more urgent even than street crime, poverty or COVID-19.

“Guatemalans didn’t get the vaccines due to corruption. Guatemalans don’t get better jobs due to corruption. Crime besieges streets in the city due to corruption,” Haug told AQ.

This is part of why recent headlines have resonated so powerfully here. In just the last six months, 24 judges and anti-corruption prosecutors have fled the country, and six others have been detained. Many have publicly accused Porras of undermining corruption investigations and pressing charges against them simply for doing their jobs. The charges targeting judges and prosecutors come amid a broader crackdown against civil society by the Public Ministry (PM), led by Porras. Over 300 civil society leaders were hit with criminal charges in 2020 alone, according to the Unit for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders in Guatemala (Udefegua).

Porras’ selection has been so front-and-center that it even hijacked the blockbuster release of The Batman in Guatemala City, where meme culture and casual conversations can’t seem to resist Gotham City comparisons. A tweet from Edie Cux, the legal director of Transparency International’s local office, summarized the mood:

I’m watching the new Batman movie and at the same time following the election of the AG. In Gotham City corruption reaches all State structures, same as in Guatemala, even the universities. The difference: Guatemala is real.

Meanwhile, Giammattei has praised Porras’ oversight of the expansion of the PM. In April 2021, Porras announced that for the first time the PM had offices open in every municipality in the country, a project supported by USAID. But just five months later, the U.S. State Department added Porras to its Engel List of “Undemocratic and Corrupt Actors” after she fired Juan Francisco Sandoval, the prosecutor at the head of the Special Prosecutor’s Office Against Impunity (FECI). Sandoval immediately fled the country, and said he was fired because he had gathered evidence of corruption schemes linked to high-ranking officials including Giammattei himself.

That makes Porras’ renewal as attorney general an unmistakable message for civil society. With Porras in place, “the PM will reinforce impunity for the powerful,” Patricia Gámez, a criminal trial judge and attorney general nominee in 2018, told AQ.

But it is also a shot across the bow for the Biden administration, which has sought to curb migration by cracking down on corruption through Engel List sanctions on key powerbrokers like Porras. On May 11, Giammattei said in a speech to mayors that the Engel List “no vale nada”—that it means nothing. He added that he would start his own “lista de zopilote,” or “vulture list” of “enemies of Guatemala.” And soon after naming Porras for another term as attorney general, Giammattei announced that he would not be attending the upcoming Summit of the Americas hosted by the U.S. in Los Angeles, another rebuke of U.S. efforts to influence his administration.

Despite a discourse focused on popular family values and crackdowns on petty crime, Giammattei’s approval ratings are estimated at under 30%. As the pressure cooker boils and periodic demonstrations continue, the path to the general elections in 2023 will be fraught. Even The Batman can’t match Guatemala’s drama.

—

Méndez Arriaza is a Guatemalan journalist and the co-founder of ConCriterio, a TV and radio program that covers politics, business and culture.