MEXICO CITY — Mexico does not do presidential reelection. Even the most paranoid opponents of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador never seriously believed he would seek to stay in the top job, as other Latin American leaders have.

Instead, in October, he will be succeeded by Claudia Sheinbaum, who, he made clear, was his preferred choice to carry the mantle of his political movement. But what explains Mexico’s reelection phobia—and how much power will López Obrador be able to exert behind the scenes once he leaves office? A look back at Mexico’s political history provides hints.

Close to 10% of Mexico’s population is thought to have died in the country’s bloody 1910 revolution—all, arguably, because Porfirio Díaz, Mexico’s dictator from 1871 to 1911, reneged on a promise to stand down. As recently as 2016, officials were compelled to sign off correspondence with Sufragio efectivo, no reelección, the Revolution’s slogan. It is still one of the few non-partisan points of agreement. To be Mexican is to oppose reelection; it is a sort of collective historical trauma.

Yet Mexican politics is also staunchly presidentialist. How to reconcile an anti-reelection national identity with almost every strongman’s penchant for self-perpetuation? The answer to this question emerged at the tail end of the Mexican Revolution in 1920. The dedazo, often described as “presidential handpicking,” is the practice and privilege of Mexican presidents to choose their own successors. To receive the dedazo is to be truly a-pointed with the presidential finger.

“It’s not like … López Obrador is going to have a red phone in [his home] to give me instructions every day,” quipped President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum. But the worry that López Obrador will be pulling the strings behind her presidency has kept many up at night, and not just because of lingering sexism or worries about the president’s enormous personal appeal. Instead, it is how the dedazo looms in the popular imagination that generates persistent concern.

Across Mexican and world history, anointed successors have been common. But what was peculiar about the form of dedazo that emerged after the Revolution was how secretive yet systematized it was. The more historians have probed into how presidents wielded it, the less straightforward it appears to have been. It wasn’t just a decision left up to the president’s whim. Rather, it was for each president a careful institutional balancing act, as well as a final effort to decide what Mexican politics would look like without him.

The myth of the dedazo

Traditionally, the myth of the dedazo envisions Mexico’s imperial presidency concentrating all power in the one person in charge of the country, though revisionist historians have cast doubt on this “great man” interpretation.

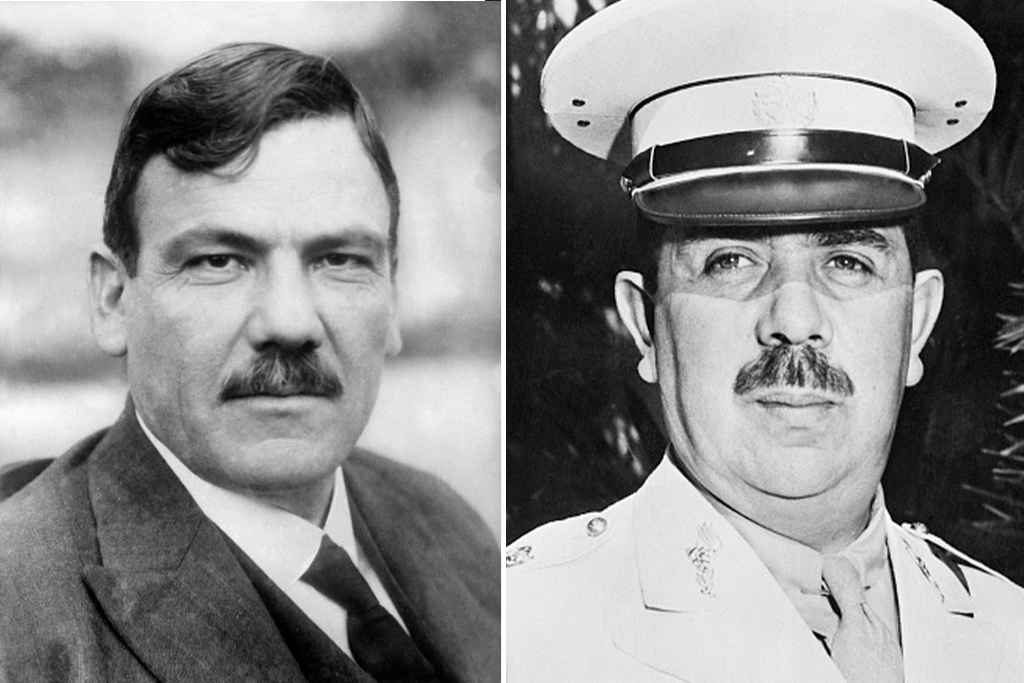

The archetype was perhaps truest to form after Álvaro Obregón, the triumphant revolutionary general and president from 1920-24, was murdered just before he was able to take power again in 1928. His ally and successor, Plutarco Elías Calles, set about to institutionalize the forces that had backed Obregón. From 1929 until 1934, Mexico had four presidents, each handpicked by Calles, who pulled the strings of power from behind the scenes.

But Calles’ final pick, General Lázaro Cárdenas, was his undoing. When Cárdenas rose to the presidency, he quickly packed the meddling ex-president into exile. A new precedent was set. A president could choose his successor, but on the condition that he’d relinquish power as soon as he left office.

The dedazo as we have come to know it was born.

Ullstein Bild archive via Getty / Bettman archive via Getty

The successor’s secession

Cárdenas reconfigured the ruling party, joining the sectors of society that backed him under one banner. His rule was marked by left-wing policy and, had he had his way, he would have named Francisco Múgica as his successor. Múgica was a true leftist; he nationalized the railways as economy minister and was close to the workers’ and peasants’ unions. But the prospect of him as president was too much for the monied and conservative classes, who, together with state governors, pushed for a candidate more suitable to their interests.

Their efforts worked, and Cárdenas chose another general, Manuel Ávila Camacho, as his party’s presidential candidate. It was a consensus dedazo, by no means democratic, but made through a system that recognized certain checks on the president’s preferences.

The dedazo worked in more or less the same way for decades. Presidents chose successors who were often not their first pick. By the final quarter of the 20th century, calls for democratization led President José López Portillo to institute political reforms that set the stage for the country’s eventual transition away from the PRI’s one-party rule. The reforms extended even to the dedazo, as López Portillo announced a pool of six potential candidates to replace him.

The eventual winner, Carlos Salinas de Gortari, got a note from López Portillo saying “eres presidente de la República y hazte bolas” (“You’re the President of the Republic, it’s your can of worms”). López Portillo understood that he was ultimately no more than, in his words, “the needle on the scale” of Mexican presidential politics.

The practice today

The end of PRI rule in 2000 didn’t necessarily put an end to the dedazo. Many would argue it persists to this day, but because of its deliberately opaque nature, one can only speculate about its existence.

Those who accuse the current government of reproducing this old and shady PRI tactic include opposition figures who dislike López Obrador, as well as some within his Morena party who didn’t like the choice of Claudia Sheinbaum, the former mayor of Mexico City.

“The people must decide, not el dedazo,” said former Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard, as Sheinbaum pulled ahead of him in the contest for Morena’s presidential nomination.

At no point did the president openly endorse Sheinbaum over her rivals. He even spoke out against the dedazo. Yet his supporters came to understand that Sheinbaum was his preferred candidate, and his perceived endorsement—coupled with his enormous popularity—became akin to a dedazo. Sheinbaum beat Ebrard in Morena’s internal selection vote by 13%.

Shades of the dedazo also appear through Morena’s well-meaning but byzantine party rules. Clara Brugada, now Mexico City’s mayor-elect, for example, initially lost the internal vote to run for the position to Omar Harfuch, Mexico City’s security chief under Sheinbaum. But due to new gender parity rules, Morena had to have a certain number of female candidates for certain posts, and Brugada was chosen to meet those requirements. Other women had run and lost by smaller margins to male rivals and could have been elevated to meet the quota; it can’t have hurt Brugada that she was closer to López Obrador than Harfuch was.

Other times, dedazo-like tactics seem to crop up with no reference to established norms. Recently, Luis Morales Flores, an Indigenous Morena deputy-elect, was inexplicably replaced with Sergio Mayer, a former TV actor close to Claudia Sheinbaum’s team.

The dedazo has become shorthand for undemocratic appointments in Mexican politics. But it also carries with it the implicit sense that successors must fight to escape their predecessors’ influence. In that sense, Mexico indeed feels like it’s back to the future, with a powerful president handing power to a chosen successor who has to learn how to make her own way in government.

In recent remarks steeped in historical symbolism, López Obrador said that whispers of global conflict reminiscent of World War II are growing, and that Sheinbaum had suggested to him that she might invite him back into the Cabinet, as Ávila Camacho did with an increasingly vocal Cárdenas. Ávila Camacho made Cárdenas defense secretary from 1942 until 1945. Perhaps to keep the former president’s council and experience close—or perhaps to keep him quiet and on side.

—

González Ormerod is founder of The Mexico Political Economist, which covers Mexican politics and policy for a global audience.