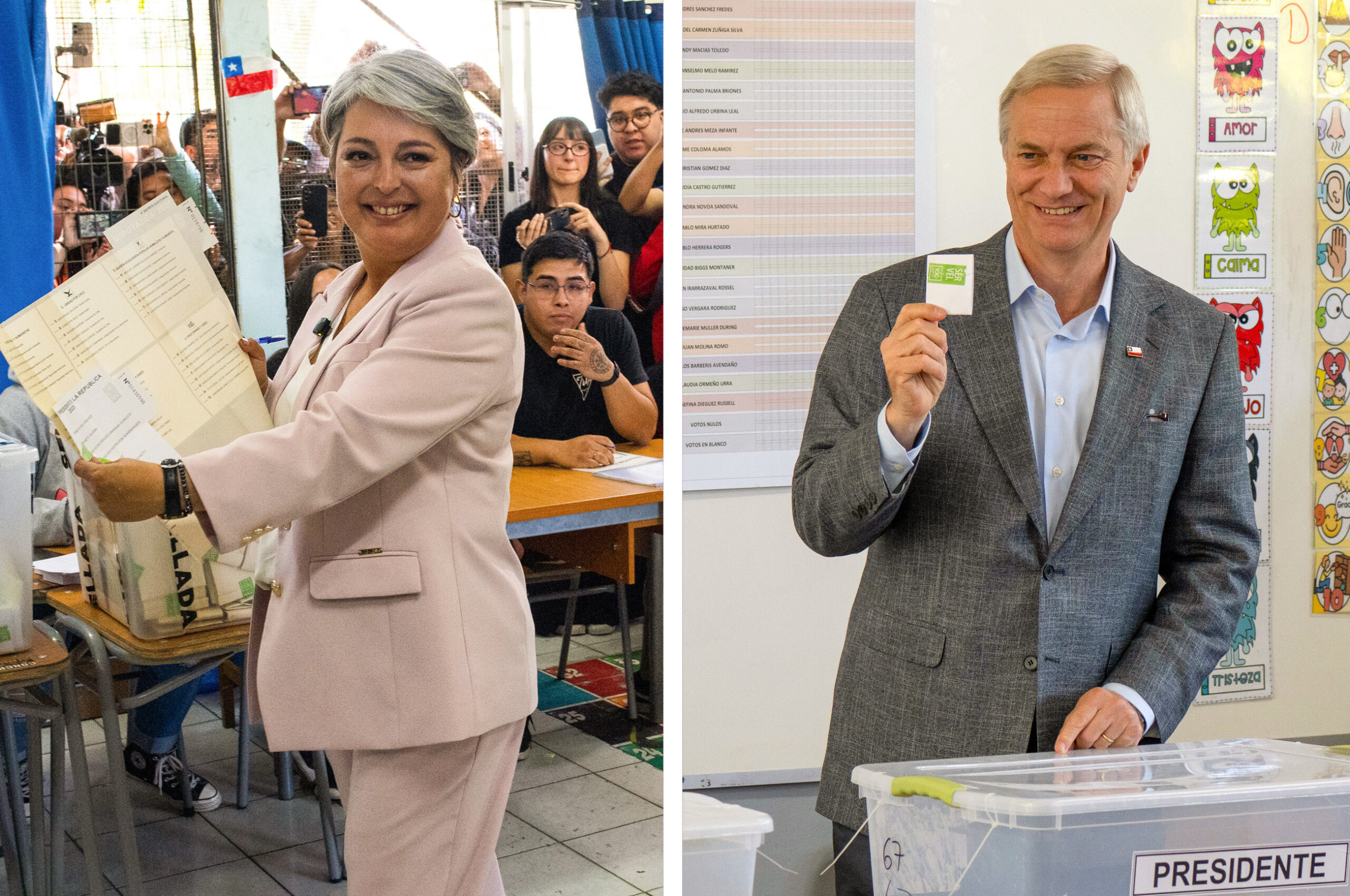

Jeannette Jara of the Communist Party and José Antonio Kast of the Republican Party will head to a runoff on December 14 after winning the most votes in the first round of Chile’s presidential election held on Sunday.

Jara won 26.85% of the votes, and Kast secured 23.92%, according to official results. In a surprise move, former polling frontrunners Johannes Kaiser and Evelyn Matthei came in fourth and fifth, while outsider candidate Franco Parisi placed third with 19.71%.

Chileans also went to the polls to elect 23 Senators and all 155 seats in the lower house of Congress.

AQ asked analysts to share their reactions and perspectives.

Rossana Castiglioni

Full professor of political science, Universidad Diego Portales

This election was the most surprising in recent Chilean history. Most pundits, scholars, and recent public opinion polls had predicted that Jeannette Jara, representing the incumbent left-wing coalition, and José Antonio Kast, representing the conservative right, would advance to the second round. Beyond this expectation, however, all other results were surprising, if not shocking, likely because this was the first presidential election with mandatory voting for the entire electorate, and we know much less about new voters than about regular ones.

First, hardly anyone anticipated such a narrow margin between the left and right-wing candidates. Second, the leader of the Partido de la Gente (PDG), Franco Parisi, performed far better than expected, finishing in third place. Parisi had been residing in the U.S. until very recently, conducted most of his campaign on social media with limited financial resources, and was surrounded by several scandals and accusations. Finally, it was also surprising that Johannes Kaiser, a newcomer to politics who recently founded his own party, and Evelyn Matthei, an experienced and well-known politician, were very close in votes, finishing fourth and fifth, respectively.

The outlook appears grim for the incumbent Chilean left. Given the current results, it will be difficult for Jara to become Chile’s next president, as the combined votes of the right-wing candidates far exceed hers. In fact, this marks the weakest electoral performance for a left-wing candidate since Chile’s transition to democracy in 1990. All right-wing contenders promptly endorsed Kast once his advancement to the second round was confirmed. Moreover, the congressional elections held concurrently with the presidential vote favored conservative candidates. Neither bloc holds enough seats to pass legislation of constitutional rank, making the support of Parisi’s PDG—whose leader has yet to commit to either presidential candidate—decisive. Securing his backing and promoting cohesion within the winning coalition will therefore be essential to ensuring governability.

Robert L. Funk

Associate professor, Faculty of Government, Universidad de Chile

Upon winning his primary in 2021, Gabriel Boric declared, “If Chile was the cradle of neoliberalism, it will also be its tomb.” Four years later, neoliberalism and its political cheerleaders seem as popular as ever.

As expected, after Sunday’s elections, Jeannette Jara and José Antonio Kast will face each other in a runoff on December 14. Jara, a member of Chile’s Communist Party, obtained just under 27% whereas Kast, of the Republican Party, almost tied her at 24%. Indeed, the combined vote for the right’s candidates is just over 50%, while the last time the left did this poorly was way back in 1958. It is difficult to envisage where Jara has room to grow.

Given the positive electoral outlook for Kast and his allies, can we speak of a rightward shift in Chile?

For at least the last two decades, Latin American elections have been described as ideological shifts or “waves.” In reality, what has happened has been more of a pendulum, with voters rejecting incumbents and hoping for something new. This dissatisfaction has been expressed in support for non-traditional political parties, personalistic leaderships, and often, massive street protests.

The current Chilean election, in which only one of eight candidates—Evelyn Matthei—represented establishment parties, must be seen in this context. Voters supported the right, but more than that, they voted against the establishment, which also helps to explain the exceptionally strong showing of Franco Parisi, a populist independent candidate who came in third place with 20%, and whose Party of the People became the vital swing vote in both houses of Congress.

In the run-up to the runoff in December, both coalitions are likely to play to fear: Communism versus fascism. This is a mistake. If there is one lesson of last weekend’s election, it is that voters supported candidates who addressed the concrete preoccupations they’ve been expressing for some time: the fear, uncertainty, and insecurity that crime, immigration, and the economy present going forward.

Loreto Cox

Assistant professor, Universidad Católica de Chile School of Government

The Chilean runoff will be contested by Communist Jeannette Jara, who secured 26.8% of the vote, and Republican José Antonio Kast, with 23.9%. Jara is the candidate of the governing coalition, but obtained fewer votes than President Boric’s approval levels, which have been around 30% for most of this year. Kast came close behind despite the right being split across three or even four candidates (depending on how one classifies Franco Parisi, the anti-establishment contender who unexpectedly placed third).

This outcome confirms the formidable strength of the right in an election where crime is overwhelmingly dominating voter priorities. Even excluding Parisi, the three clearly right-wing contenders surpassed 50% of the vote. And with strong anti-incumbent sentiment surrounding this election, most of Parisi’s voters are likely to break for Kast.

The election also confirms the loss of appeal of the two coalitions that dominated Chilean politics during the first three decades after the return to democracy, paving the way for parties at their extremes. It is unclear to what extent this shift reflects growing polarization or a deepening aversion to traditional politicians.

Another revealing outcome was the emergence of sharp regional divides, a relatively new phenomenon in Chilean politics. Parisi carried the mining north; Jara prevailed in the central regions, home to most of the population; and Kast dominated the agrarian south, except for the two far-southern regions, which favored Jara. These geographic contrasts, together with widening differences between rural and urban areas, point to an increasingly segmented political landscape.

The congressional elections also reflect the rightward shift and the sorpasso of this new, more extreme right at the expense of the traditional center-right. Seventeen parties won seats in the lower chamber, down from 22 in 2021, yet still indicative of a highly fragmented party system that is likely to complicate political negotiations.

This was a gloomy election for Boric’s coalition. But four years ago, the gloom fell on the right. Whether this new landscape is durable remains to be seen.