Tarciana Medeiros was eight years old when she first started helping her dad out at his fruit and vegetable stand in a street market. At 45, she now runs the bank that is Brazil’s main lender to agricultural producers who grow the very foods she used to sell with her dad.

Medeiros is the first woman ever to lead Banco do Brasil (BB) in its 200-year history. She’s also many things most people in such positions are not: she’s Black, she’s from humble origins, she’s from the country’s northeast, and she’s gay. And she has stepped into the role at a time when the bank is at the crossroads of some of Brazil’s core existential questions.

As the main lender to agricultural producers, big and small, vegetable growers and meatpacking industries, BB is a key institution in the challenging equation of agribusiness’ expansion and environmental sustainability.

Meanwhile, at the end of her first year in office, another of Brazil’s core issues came knocking on her door. In October 2022, prosecutorial authorities opened an investigation into the participation of slave owners in the bank’s ranks in the 19th century. As such, the bank became implicated in one of Brazil’s central questions – how to address the enduring legacy of slavery in the country that was the last in the Americas to abolish it.

From fruit stall to key player in agribusiness

The Medeiros family stall was in Campina Grande, a mid-sized capital in the comparatively poor northeast of Brazil. Between the ages of 8 and 15, Medeiros was her father’s main assistant, while her mom stayed home with her three younger siblings.

Although she worked daily with her father and cites business lessons she learned from him, most often she alludes to her mother and aunt as formative influences. “Mainha (a tender way in Portuguese to refer to one’s mother, particularly common in the northeast) and ‘titia’ (auntie) taught me that education can lead us to the top, and that that top would mean different things to different women, but that we could do whatever we wanted in this world,” Medeiros told Forbes last year.

Medeiros started out at Banco do Brasil as an office clerk at a branch in a small town. She studied business administration and rose through the ranks until she reached a post of executive manager, in Brasília, the country’s capital.

When the administration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office in 2023, progressives were clamoring for more representation in key public roles. With so many setbacks in previous years under former President Jair Bolsonaro, expectations were high. Lula determined early on that the next president of Banco do Brasil would be a woman. After a round of interviews, Medeiros got the job.

Despite her appointment and some other initiatives that advanced representation, such as the creation of a ministry for Indigenous peoples, the first year of Lula’s third term as president has also been marked by disappointments on this front, with women ministers being dismissed to accommodate political agreements and the nomination of white male justices to Brazil’s Supreme Court.

Agro’s biggest partner

As Medeiros marks a year in her role as president of BB, the bank has produced excellent financial results. The story on the environmental front is more complicated.

Agriculture is Brazil’s economic engine, representing 25% of GDP, 20% of employment and around 40% of exports. It was responsible for Brazil’s better-than-expected GDP results in 2023. It also poses major risks. Deforestation and other harmful practices threaten what is arguably Brazil’s greatest asset, its forests.

The Lula administration came in with the promise of stopping the rampant deforestation seen under Jair Bolsonaro, as well as helping the Brazilian economy transition to greener, sustainable models. Indeed, deforestation in protected areas has gone down by 73% in 2023.

But policies for the second part of the equation remain a challenge. The administration’s relationship with the agricultural sector is delicate, as a significant part of it supports the right, and sided with Bolsonaro in recent elections. Aside from depending on agriculture for economic growth, the government also depends on the sector’s significant caucus in Congress to approve reforms.

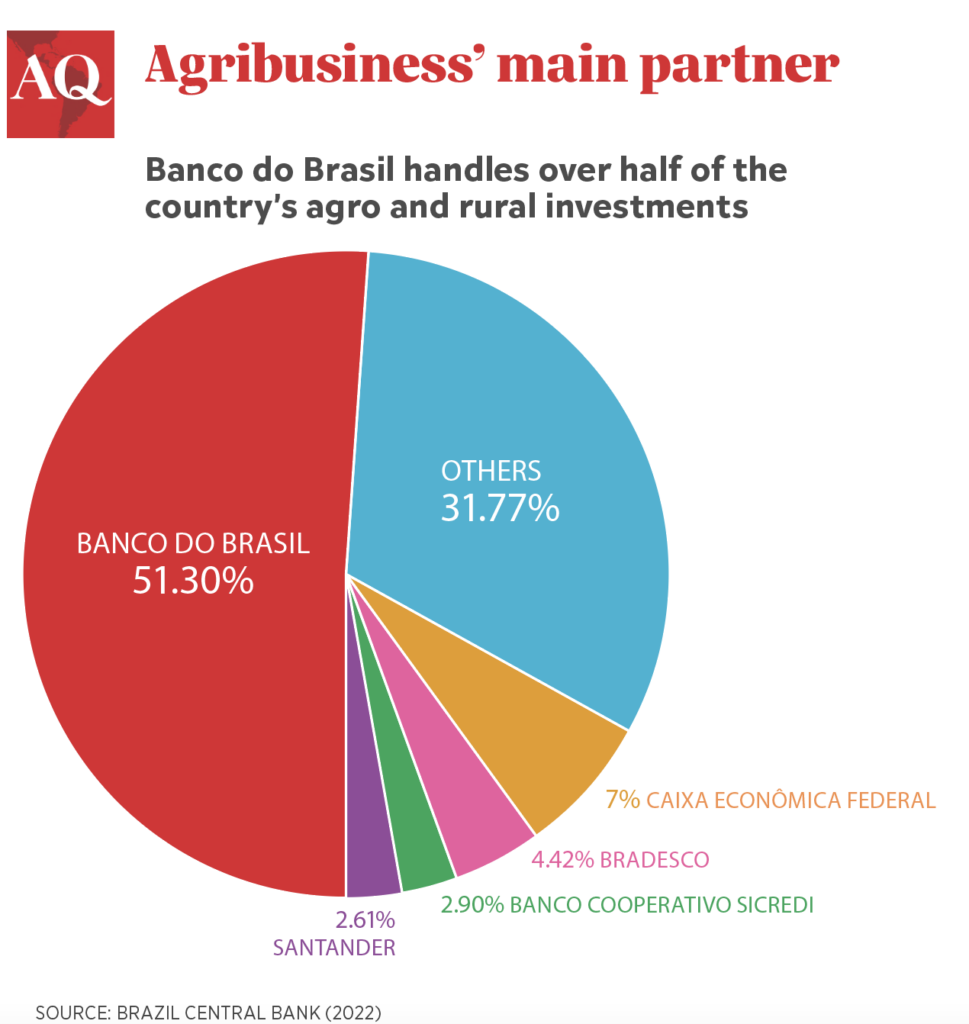

Banco do Brasil is a key participant in this puzzle. Historically its role has been to provide capital in general, but especially for agriculture and agribusiness ranging from small, family-run vegetable patches to large companies. “Without BB and without Embrapa (an entity that foments technological development of agricultural practices) Brazil would not be the agricultural powerhouse it is today. As agribusiness’ main lender, the bank has considerable bargaining power in the green transition agenda”, says Fernando Nogueira Costa, from Unicamp (Universidade Estadual de Campinas), who has written a book about the bank’s history.

BB often wins awards for sustainability. Sustainable initiatives currently make up 35% of the bank’s credit portfolio, according to the institution. Also according to the bank, 52% of loans in 2023 went to small producers, the kind of agricultural activity that is less harmful to the environment and that this administration has said it wants to foment. In September, the bank and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) signed a letter of intent to create a $250 million credit line to fund sustainable development in the Amazon.

However, the bank holds shares in Brazil’s largest meat processors, including JBS, despite multiple studies showing beef is the commodity that contributes most to deforestation in Brazil. A report in 2023 by NGOs indicated that JBS has had ties with illegal deforestation. (In a statement to Folha de S.Paulo the company said it had severed ties with most of the suppliers mentioned in the report.)

Banco do Brasil said in response to these claims that its credit provides for compliance with socio-environmental criteria.

Banco do Brasil’s role in slavery

BB is one of the country’s oldest institutions. It was founded in 1808, the year the Portuguese royal family moved to Brazil, to begin to establish sources of credit in the country.

Historians have found, and BBC Brasil revealed, that money from the slave trade made its way into the bank’s coffers in a few different ways. No country in the Americas enslaved more people: Between 1500 and 1900, over 4 million Africans were forcibly brought on ships to the Brazilian coast. Part of the bank’s cash came from fees charged to vessels dedicated to trafficking Africans, and a founding member of Banco do Brasil was a slave-owner.

Public prosecutors opened an investigation into the matter, with the intention of promoting reparatory initiatives. It’s the first attempt in Brazil’s history to hold a public institution accountable for its role in slavery.

When the BBC story first broke, the bank’s response was mixed. The lawyer-drafted official statement had a defensive tone, while Medeiros gave interviews saying the bank would not shy away from the debate. A few months later, however, it seemed her approach had prevailed. The bank issued an official apology, signed by Medeiros, saying: “Today’s Banco do Brasil asks Black people for forgiveness for its predecessor versions and works intensely to confront structural racism in the country.”

The bank also announced initiatives to address structural racial inequality in its ranks and among clients. In response, public prosecutors acknowledged the apology, but said it was not enough. According to them, the bank should invest in further studies about its past and create a forum for debate with Brazil’s Black population about reparations.

When Medeiros took office in January 2023, she said “The mission I have taken on, starting this year, is extremely relevant and challenging. I am fully aware of that.” Her first year has shown she was right.