There was never any genuine risk of a coup or popular revolution during Sunday’s riots in Brasilia, and there is no risk of one today. But there are other, still highly problematic scenarios on the table that could make life difficult for President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and damage the health of Brazil’s democracy and economy, in the weeks and months to come.

The world has been focused on the similarities between Brazil’s January 8 and the United States’ January 6, and rightfully so. But one key, and perhaps under-appreciated, detail is that in the two years since supporters of Donald Trump invaded the U.S. Capitol, there has been no further political violence on that scale in the United States. The risk is real; U.S. authorities consistently cite anti-government domestic terror groups as the biggest threat to national security. But so far, effective law enforcement, as well as the imperfect efforts by President Joe Biden’s administration to identify and punish those responsible for January 6, while also healing or at least managing the country’s political divisions, seem to have helped avoid the worst. Elsewhere around the world, including in Germany last month, similar plots have also been stopped before they went forward.

But as the old saying goes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. And there are already reasons to believe that Brazil will face a persistent risk of domestic terror and disruptions to daily life, at least in the near term. Two weeks before Sunday’s failed insurrection, authorities arrested a man who allegedly placed an explosive device on an oil tanker near the Brasilia airport, hoping to sow chaos and somehow prevent Lula’s inauguration. Since Sunday, at least three electrical transmission towers have been brought down, and three others damaged, in the states of Rondônia and Paraná, in what authorities said appeared to be incidents of “sabotage” and “vandalism.” On Monday, pro-Bolsonaro groups on Telegram and Twitter called on supporters to block access to refineries nationwide, and thus provoke fuel shortages, to destabilize the government (police were deployed, apparently hindering the plan). On Wednesday, authorities decided to once again close the Esplanade of Ministries in Brasilia, just a day after reopening it, following word that bolsonarista groups were planning a new “National Mega Protest to Retake Power.”

Subscribe to the Americas Quarterly Podcast on Apple, Spotify, Google and Soundcloud

To be sure, after any seismic event like the one on Sunday, there are always attempts at copycat attacks and a lot of heated rhetoric that ultimately comes to nothing. Barriers stood in Washington DC for months after January 6, 2021. But here we come back to the main difference between the United States and Brazil; In Brazil, the loyalties of the military and police forces are fundamentally in doubt. Remember, Bolsonaro’s was in some ways a military government, with active-duty or retired soldiers at one point composing a third of his Cabinet and holding hundreds of key federal posts. Today, the military would not lead or support a coup or other effort to remove Lula from power; senior officers, especially, are aware that neither a majority of the Brazilian people nor the international community would tolerate such a thing. But in a country with Brazil’s size, complexity and political divisions, having anything less than the total loyalty of the security forces can still pose significant challenges to governability.

Consider, for example, what transpired the day of the runoff election in October, when Brazil’s highway police stopped buses carrying voters throughout Brazil’s Northeast, where Lula’s base lives, in an attempt to either harass or stop them from voting. Those tactics only stopped after a direct order from Brazil’s Supreme Court. On Sunday, emerging evidence suggests some police and soldiers not only stood aside, but actively aided the rioters who sacked the presidential palace, Congress and Supreme Court. Brazilian media have reported that Lula was hesitant to deploy the military to stop the riots because he was uncertain as to whether Bolsonaro loyalists within the ranks might make matters even worse. Lula’s apparent decision to retain his defense minister, whom military commanders like and trust, despite widespread calls on the left for his resignation, suggest the president believes the situation is delicate and wants to accommodate the armed forces where possible instead of purging its ranks of Bolsonaro loyalists.

I am still fairly optimistic about Lula’s, and Brazil’s, chances of avoiding the worst. Lula has so far mostly projected authority and calm, showing he is in charge and vowing to prosecute those responsible for the riots, while also steering clear of unnecessary divisions. Voices across the political spectrum, including several former Bolsonaro ministers, as well as all of Brazil’s governors, rejected Sunday’s events with a unanimity and strength that eluded their U.S. peers in 2021. I also–and this is completely unscientific, but bear with me–question whether Brazil has the same history of militia culture, and tradition of fruitless foreign wars, that have swelled the ranks of angry, radicalized, combat-savvy young men in the United States.

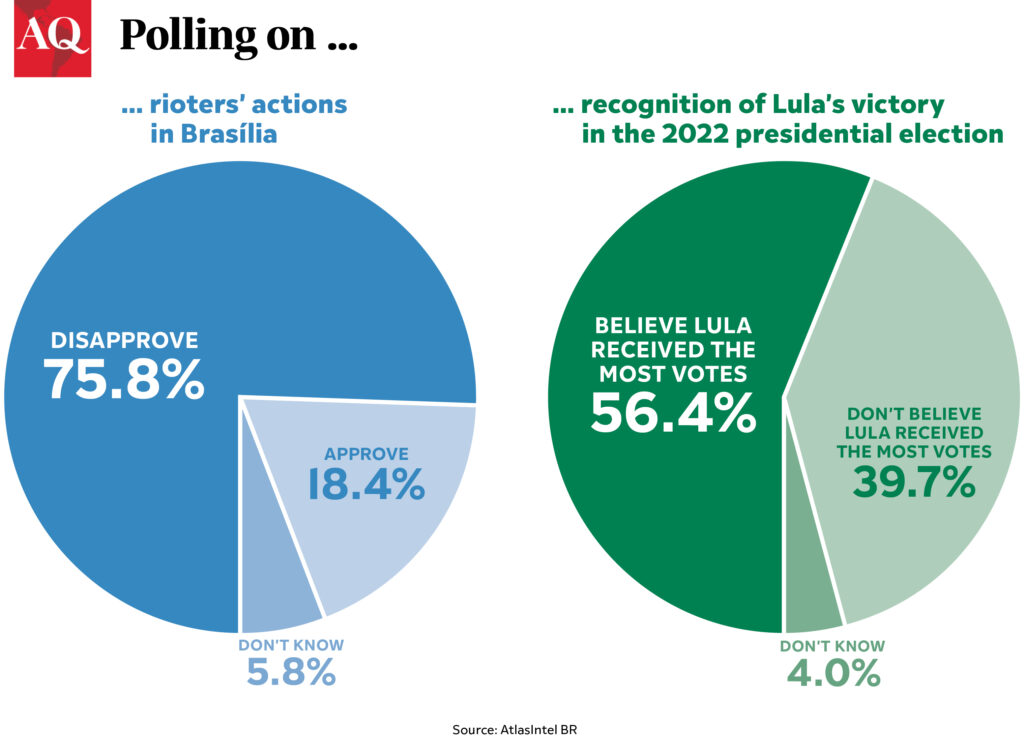

But these are also changing times, for Brazil and the world. A poll this week showed that while 75% of Brazilians disapproved of the failed insurrection, 40% did not believe Lula was the legitimate winner of October’s election. (In another parallel, polling in the U.S. suggests a nearly identical percentage still questions Biden’s win.) Domestic terror is not the only risk; further polarization could result in street protests, the future election of candidates who fundamentally question democracy and elections, and more. Right-wing social media bubbles have already built an alternate universe in which Sunday’s demonstrators are “heroes” who were sent to inhumane government gulags (“Lulags,” some called them) and the only violence was caused only by infiltrators. Meanwhile, the counter-reaction to all this will not be just up to Lula; the actions of Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes, who wields a degree of power with no equivalent in the United States, continue to worry some advocates of democracy. This week, he said those arrested for Sunday’s riots were “not civilized people … it’s not possible to speak with them.” He also not only removed Brasilia’s governor from office, but ordered the imprisonment of both the federal district’s former security chief and the ex-commander of its military police.

Perhaps history will judge such actions as necessary; there is no established manual for defusing these kinds of threats to democracy. But just because January 6 and January 8 were similar doesn’t mean their aftermath will be, too.