What’s the most realistic way to look at Venezuela’s 2024 elections? As the U.S. makes efforts to encourage negotiations between Nicolás Maduro’s regime and the Venezuelan opposition, the Biden administration has provided some sanctions relief already and is dangling the prospect of more in return for concessions regarding elections.

Even with concessions, elections in Venezuela—endorsed by the opposition, the Maduro regime, the United States and the international community—will involve a stacked deck. But they’re the only game in town, and they represent a critical opportunity for opposition parties to rebuild their organizations and reconnect with grassroots movements. Following years of electoral boycotts and participation under duress, Venezuela’s opposition parties desperately need to connect with voters and road-test ideas. The Biden administration should push much harder to help the opposition win concessions from the regime, but it must also be mindful of the downsides involved in this strategy.

Venezuela’s political transition is a highly complex process that involves social, economic, security and political factors unlikely to be resolved in a single election. And if there’s one thing chavismo has proven, it is that elections do not equal democracy. Even so, the upcoming elections provide an opportunity to engage in important retail politics. Apathy has set in among Venezuelan voters, and too many feel that politics is no longer the best vehicle for change.

In theory, electoral participation presents a chance to prepare the next crop of emerging leaders to carry on the opposition’s fight—though the current list of candidates mostly includes also-rans from the past decade of opposition politics. These figures must reengage one of the world’s largest diasporas: 7.2 million have been forced to migrate, all of whom have the constitutional right to vote from abroad. The primary process, meant to unify a fragmented opposition, will serve as an important indicator of the main opposition parties’ staying power and future role.

But even the ability to compete in an election requires concessions from the Maduro regime: loosening of state control over the media space and revoking the anti-hate law, mechanisms allowing the diaspora to vote reliably, freeing political prisoners and removal of widespread candidate bans. Sanctions relief so far—for Chevron but also members of Maduro’s wife’s family—has given the impression of a U.S. administration eager to move the needle on Venezuela but unable or unwilling to do so. The truth is that there have been no meaningful developments in the Venezuela negotiations for months, and regime heavies, including Maduro himself, have gone so far as to pronounce negotiations dead.

Petro steps in

Stalled negotiations provided Colombian president Gustavo Petro, who has expressed sympathy for Maduro, an opportunity to step into the void. Recently, Petro hosted a summit on Venezuela, ostensibly to jumpstart negotiations, but the agenda was rather amorphous and the event featured participation neither from the opposition nor the Maduro regime.

In the end, the conference participants issued a short statement agreeing on what needs to be agreed upon between the Venezuelan opposition and Maduro regime: an electoral timeframe with better conditions, a reciprocal lifting of sanctions and the implementation of a previously negotiated accord for humanitarian assistance. Petro’s efforts don’t seem to have provided the necessary spark to restart negotiations with a regime that has delayed and resisted calls to return to the table—at least not on a timeline that would synchronize with elections.

After the Bogotá conference, it’s not inappropriate to wonder whether Petro, or Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, will serve salutary roles in resolving Venezuela’s crisis. Recent events involving former interim president Juan Guaidó, who was urged to leave Colombia by officials after crossing the border by foot, have raised doubts about Petro’s ability to mediate fairly between Maduro and the opposition. For his part, Lula appears more taken by events in Ukraine, employing much of his political capital to sell the idea of a “peace club” of nominally non-aligned countries to negotiate an end to the conflict. Further, it’s likely Lula would encounter domestic resistance if he were to push Maduro too hard, since the latter enjoys sympathy within some segments of Lula’s Workers’ Party.

In the worst case, both Petro and Lula could end up providing cover to Maduro as he seeks to consolidate his position heading into the election. On this reading, the recent summit was nothing more than an attempt to make Maduro-friendly policy look more principled.

Summit diplomacy notwithstanding, negotiations between the opposition and regime may prove difficult to restart. Meanwhile, regime insiders are declaring their victory in elections a foregone conclusion and staking out maximalist positions on sanctions relief and on an end to the International Criminal Court’s investigation of the Maduro regime for crimes against humanity as a condition for returning to the negotiating table. In past negotiations, Maduro has made similarly expansive demands to signal his desire to talk has ended.

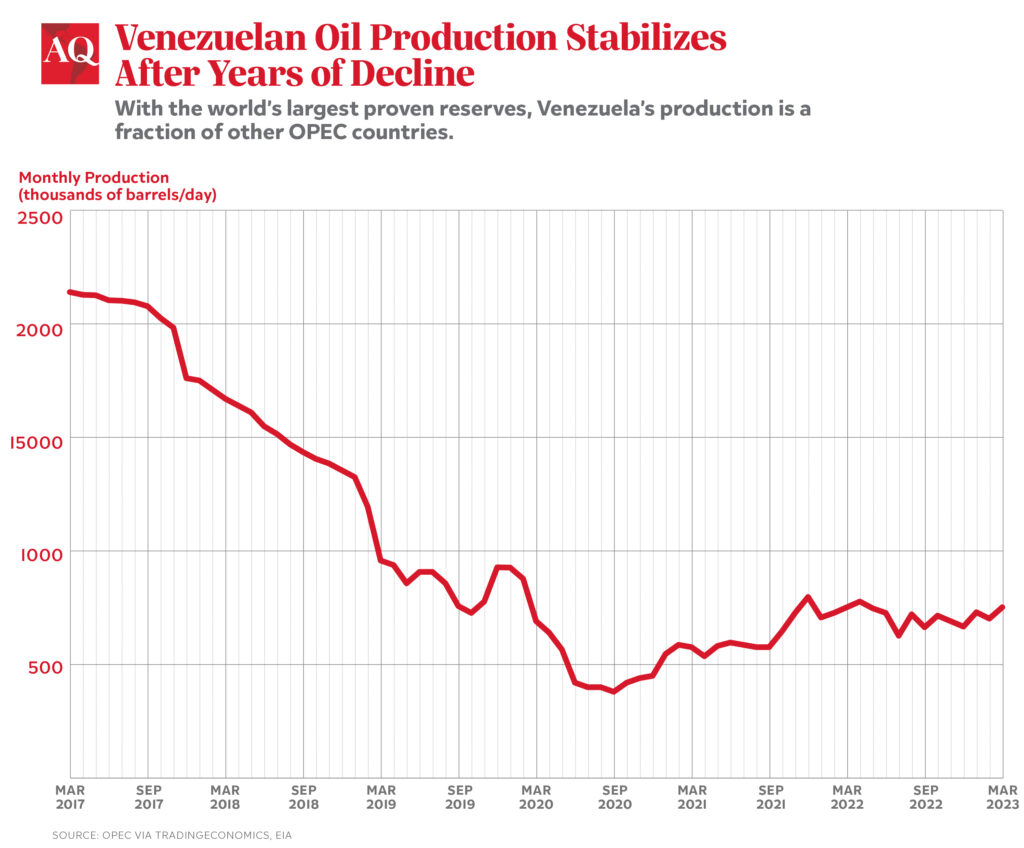

Maduro’s long-term goal has always been a reduction in his regime’s isolation and, eventually, normalization of relations with the West—especially the United States. Indeed, his strategy over the last year has been calculated to earn greater legitimacy from the international community. International fatigue, the dissolution of Juan Guaidó’s interim government, and a changing regional landscape have conspired to bring this goal closer to reality. Some regional leaders may even be wagering that a recognized, stabilized Maduro may be able to better stanch the flow of migrants out of Venezuela. In the shorter term, Maduro would like tough sanctions on PDVSA, the state-owned oil company, lifted so that his regime can access international markets and greater financing. The company’s sanctions workarounds have been carried out by little-known intermediaries, which has been disastrous for PDVSA. It now contends with a massive corruption scandal and more than $20 billion in unpaid bills, which led to the purge of regime heavyweight Tareck El Aissami, the erstwhile Minister of Petroleum.

The U.S. political equation

The U.S. also has a presidential election coming in 2024. If Maduro senses that Republicans have the upper hand in the election, he may choose to prod Venezuela’s pliant national electoral institution to move up the date of the country’s presidential election, seeking to lock in relaxation of sanctions—or even normalization of relations—with the U.S. before the White House changes hands.

If the Biden administration moves to normalize relations with Venezuela following a potential Maduro reelection, it would be nearly impossible for a Republican administration to reverse course, especially in the absence of an obvious alternative to recognize, such as the recently dissolved interim government.

On the other hand, if Maduro senses that President Biden will win a second term, he may decide not to assume the risk of tampering with the electoral schedule and hold it at the end of 2024, confident in his ability to lock in sanctions relief and potentially a full normalization after the elections.

Reasonable expectations for Venezuela’s elections

The stakes of the 2024 elections are high, but they represent not the end but the starting point of change in Venezuela. They are unlikely to offer a repeat of the 1988 plebiscite in Chile that marked the end of the Pinochet dictatorship. Chavismo is unlikely to allow itself to be defeated electorally, which would mean the loss of immunity just as a case for crimes against humanity is heating up in the International Criminal Court.

But the opportunity for the country’s opposition to rebuild political muscle memory in rough and tumble Venezuela should not be discounted—it could yield results not only in the 2024 elections, but also for 2025 local, state, and parliamentary elections. This is despite the fact that there are also significant downsides for both U.S. and international policy that often go unmentioned and must be recognized and mitigated—starting immediately.

Maduro’s nearly guaranteed victory in 2024 is likely to be recognized by regional governments. The election could also defrost relations between Venezuela and the European Union. Spain, often the leader of the bloc’s policy toward Latin America, already moved to recognize Maduro and appointed a new ambassador to Venezuela in December 2022. Regional governments moving in conjunction with the European Union could force the Biden administration to normalize relations with Venezuela to avoid isolation as one of the few governments that does not recognize Maduro.

The Biden administration must require the Maduro regime to make real concessions in exchange for future sanctions relief. Absent those concessions, and without placing the elections in their proper context, the United States may find its hands tied on Venezuela policy.

—

Berg is director of the Americas Program and head of the Future of Venezuela Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.