HUEYNAUPAN, Mexico – A remote school year has just started for students all over Mexico. But it’s unlikely to work in places like this hilltop town of 2,000 in the Huasteca mountains of Puebla state.

With the pandemic still raging, students are meant to log into internet platforms and virtual classrooms. The government plan will also use television programming, staggered for different age groups over the course of the day, and several Mexican TV networks will carry classes.

But in Hueynaupan, even over-the-air TV signals are spotty. The primary link to the outside world is a small store, which sells everything from fortified milk to cigarettes — and WiFi passes worth 15, 30 or 60 minutes online.

Over the last 50 years, a series of government programs tried to build “tele-schools” in these rural areas using satellite TV, open air television, and satellite internet. But many rural areas have nothing to show for it now. Expensive equipment has disappeared, and a lack of program continuity has left many rural towns with no telecommunications infrastructure. Successive administrations have scrapped their predecessors’ programs, starting fresh and stunting progress.

That leaves the store. Iliana, a resident whose granddaughters studied at the nearby school in Hueynaupan before the pandemic and declined to give her last name, says that worksheets will have to be purchased at the cybercafe this fall for $0.10 a page. After her granddaughters fill out the worksheets at home, they go back to the cybercafe and send them to their teachers. “There is no open television here,” Iliana explained, saying the recently announced programs via broadcast television won’t reach her family.

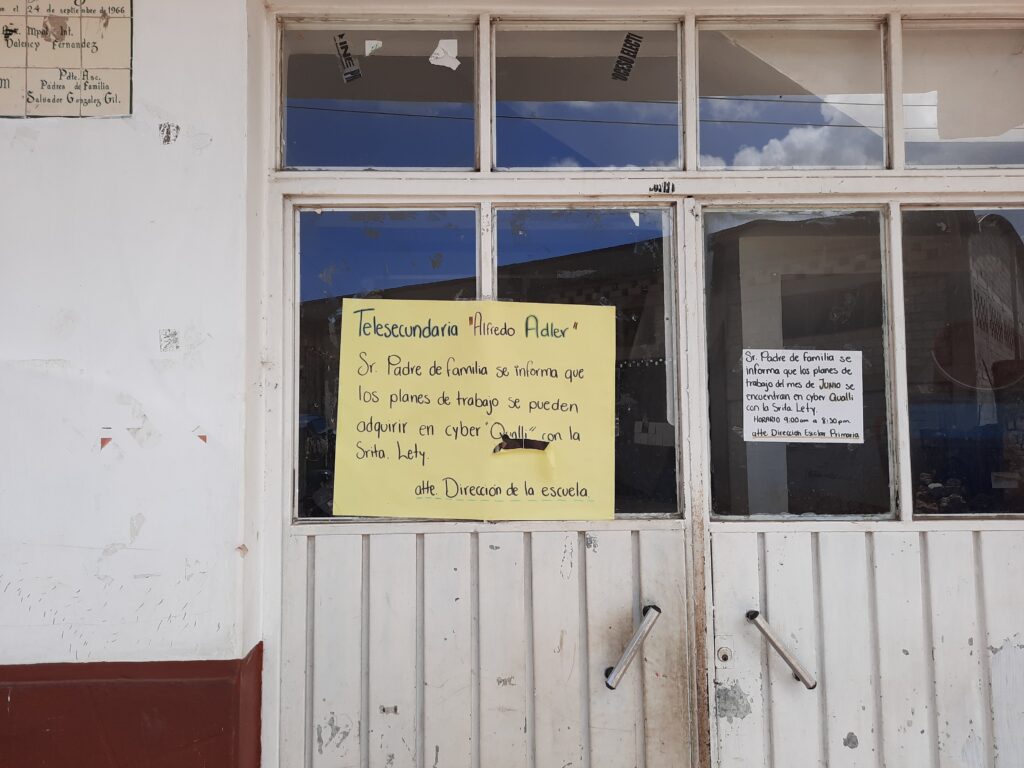

At tele-school Alfred Adler, the principal left a sign outside the door directing parents to purchase lessons at the nearby cafe.

Other public school teachers and telecommunications professionals told AQ of similar situations in the states of Guerrero, Oaxaca and Michoacán. It is a tale that is being repeated in different ways in rural and poorer areas across Latin America.

Recent initiatives from Mexico’s federal government have included the creation of the Red Compartida, which uses 90 MHz of premium national broadband spectrum, and whose network is only available via wholesale to virtual operators. The project is under the close oversight of Promtel, a government agency set up under the administration of former President Enrique Peña Nieto to ensure that remote areas without broadband options can connect. To date, only about 50% of the country is covered. In an infamous incident Mexico’s federal government distributed more than 1 million tablets in 2015-2016 to help young people connect, but the tablets didn’t have internet access, never worked and, like many others, the program was discontinued in 2017.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has similarly promoted digital inclusion, but concrete plans and financing for infrastructure have been elusive. One initiative involves the use of the Mexican public utility company CFE’s dark fiber to provide the necessary backhaul for rural broadband. However, on Aug. 10, the Secretary of Communications and Transport (SCT) dissolved the sub-secretary of communications, leaving many to wonder how the administration will regulate telecommunications.

Urban progress

According to a 2018 government report, the number of people without internet access has decreased to 34.2%, meaning 5.8% of the population gained access to the internet over four years. But the contrast between urban and rural areas where indigenous language-speaking students live is stark. While 73.1% of urban residents have internet, only 40.6% of the rural population has internet access. These numbers include all types of internet connections, including limited prepaid accounts too expensive for regular browsing. The 3.2 million students who speak an indigenous language account for 13% of the student population, concentrated in rural areas.

Public-private partnerships have also started to expand. Programs like México Conectado have announced that they are connecting 12,000 additional points via satellite internet, and most of them are schools. Facebook and Google are also putting up satellite hotspots in remote towns that provide discounted connectivity via WiFi, but so far these programs have been limited pilots.

More is clearly needed. A survey of 20 schools this summer in the Huasteca region where Nahautl, Totonaco, and Otomi are spoken, only 30% had functional telecommunications equipment, despite most being named “tele-school.” One school with 80 students didn’t have television, telephone, or satellite equipment.

Meanwhile at the shop in Hueynaupan, business is booming thanks to a WiFi antenna that gets about 300 kbps download and 100 kbps upload from a transmitter in a village a few miles away. As classes resume, students are again depending on it to get their lessons – using internet time on one of 8 computers, for $0.50 an hour.

—

Phillips is a telecommunications consultant and founder of Siglo Network, a community-run internet service provider.