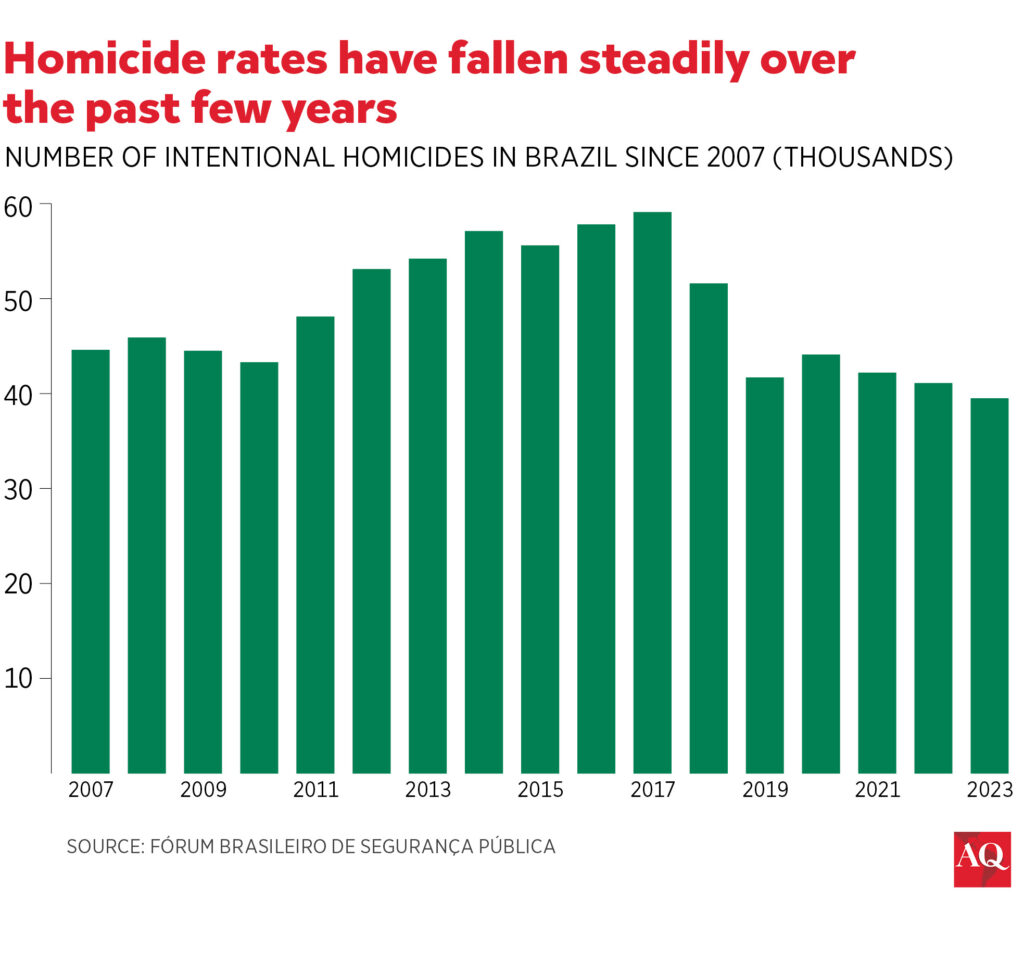

RIO DE JANEIRO — There is a paradoxical reality in Brazil today: While murders have fallen to record lows, Brazilians are deeply concerned about criminal violence. There were 39,500 intentional homicides reported in 2023, a 4% drop from 2022, when there were 41,100. Indeed, homicide rates have fallen steadily over the past few years under former President Jair Bolsonaro and President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

Yet although murders are at the lowest level in years, recent surveys show that 36% of respondents believe that violence actually increased since Lula took office and two thirds of Brazilians are still afraid of walking alone at night. Why are Brazilians feeling more unsafe than ever despite an objective decline in lethal violence? The answer is complicated.

For one, Brazilians regularly cite criminal violence as a leading concern, irrespective of whether homicide rates are rising or falling. Concerns with rising violence and personal insecurity were leading priorities in the lead-up to elections in 2014 and 2018, outstripping the economy, education, and health. Indeed, worries about crime and victimization have topped public surveys for decades. With improvements in the economic situation over the past year and the COVID-19 pandemic receding, it is perhaps natural that concerns migrate back to Brazil’s persistent and significant violent crime challenge.

And strange as it may sound, homicide may not be the most influential factor shaping the average Brazilian’s perception of insecurity in a society stratified by poverty, inequality and racism and inured to intolerable levels of crime. Other indicators like street robbery, open drug use, and even homelessness may have a stronger impact on people’s day-to-day perceptions than murder. And there are metrics that are often invisible from official statistics—from extortion to kidnapping—that can impact how many Brazilians interpret their security environment.

The role of politics

There are also ideological dimensions to how people experience and perceive public security. In Brazil, as elsewhere, the political left is routinely ranked poorly in preventing and reducing violence regardless of their actual performance. Indeed, in December 2023, the Lula administration was rated “bad” or “very bad” in dealing with security and corruption by more than half of all people polled by Datafolha. Survey after survey shows that most Brazilians feel the Lula administration has yet to deploy a coherent national public security strategy.

By contrast, the far right have consistently made public security their priority. The previous administration was heavy on its “tough on crime” rhetoric even if it was light on practical or effective responses. Rather than focusing on addressing the causes of crime, including inequality and impunity, Bolsonaro offered simple narratives emphasizing “law and order,” using force to fight crime, and empowering police. Notwithstanding efforts by the left to reclaim public security, these messages resonate, especially to far right supporters who are fearful that the situation is deteriorating.

It is also the case that media can intentionally and unintentionally ramp up public perceptions of insecurity, with social media also helping turn up the fear dial. Likewise, widely publicized police and military operations in cities across Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, and São Paulo involving shootouts often reinforce the perception that organized crime is winning. Recurring news about school shootings, prison massacres, militia-led protests, and vigilante violence all give the impression that the federal and state governments are losing control.

The truth is that regardless of whether homicide rates and perceptions of insecurity are climbing or falling, Brazil is a hyper-violent society. Even though the federal government reported a slight decline in homicide and femicide and reductions in vehicle theft, cargo theft and crimes against financial institutions in 2023 (compared to 2022), the country still registers intolerably high rates of violent victimization. Having endured among the world’s highest murder rates for decades, most Brazilians have learned to coexist with extreme violence. Although lethal violence tends to be highly concentrated in certain places and populations, the perception of insecurity is amplified by non-lethal street crime and conventional and social media.

The paradox between objective and subjective experiences of violent crime and insecurity is present in other sectors, not just public security. Despite a broadly improving economic situation in Brazil, favorability ratings for Lula’s Workers’ Party are slipping, including among those who voted for Lula in 2022. One of the reasons for this is, ironically, rising concerns about public security and corruption. The solution, naturally, is to not just talk about preventing and reducing violent crime, but prioritizing, investing in, and meaningfully improving public security for all.