This article is part of a series examining the evolving relationships between China and Latin America.

In the evolving debate over the U.S.-China relationship, and how it will impact Latin American countries, many observers perceive a recent shift. After Washington and Beijing reached their “Phase One” trade deal in January 2020, many assumed that the trade wars that peaked during the Trump administration had effectively ended. The focus thus turned instead to non-trade issues – questions of strategy, technology and ideology that seem to dominate attention today.

But the truth is that trade tensions never quite disappeared, and they are worth revisiting now, for at least two reasons. First, for much of Latin America, growing ties with China have been propelled above all else by trade and broader economic considerations — not geopolitics. Second, since the onset of the pandemic in March 2020, COVID-induced supply chain disruptions (including a massive increase in international transport costs) and trade policy restrictions have once again stress-tested global commerce, with profound implications for Latin America in the short and long term.

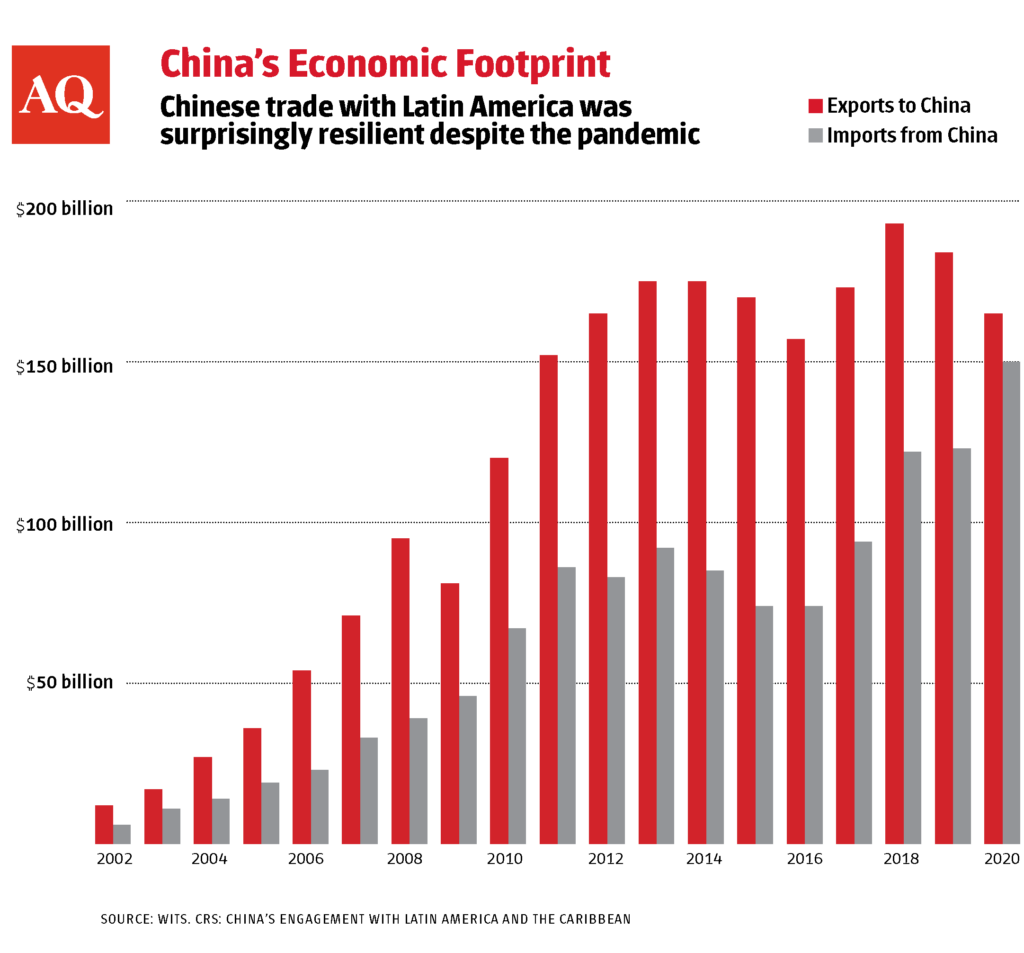

To explain, it is useful to review where the relationship stands today. Trade between China and Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) held steady at approximately $315 billion in 2020, practically unchanged from 2019. This is remarkable because the pandemic wreaked havoc on LAC exports overall in 2020, causing an estimated 11.3% year-on-year contraction (including a 14.6% decline in shipments to the U.S.). In the meantime, a fast-recovering China stood out as the only exception among LAC’s major destination markets by registering a 2.1% year-on-year increase in exports from LAC. The resilience of China-LAC trade follows an impressive 20-year trajectory between 2000 and 2020. During this period, bilateral trade grew more than 25 times (from a low base of $12 billion) and China’s share of total LAC trade multiplied eight-fold (from 1.7% to 14.4%).

The demand-supply dynamics behind these trade flows are well-known. On one hand, Chile, Peru and Brazil are among the world’s top exporters of products such as copper, iron ore, soybeans and beef. On the other, China is by far the world’s largest consumer and importer, and its demand remained robust during the pandemic. Unsurprisingly, China has become, for some time now, the number one trading partner for these and some other countries in the region. Based on current trajectories, China could overtake the U.S. as LAC’s overall largest goods trading partner during the next two decades.

In the context of COVID-19, over 100 million Sinovac, Cansino and Sinopharm vaccines are expected to flow to the region, which—together with massive amounts of personal protective equipment and medical supplies—makes China a key ally in LAC’s fight against the virus. Chinese firms have also invested in local production of vaccines, including a recently announced new Sinovac plant in Chile. The U.S. has also made recent, if belated, inroads in “vaccine diplomacy,” having distributed about 38 million doses in the region as of mid-August.

Tensions likely to persist

Despite the aforementioned competitive dynamics, however, discussions about direct U.S.-China rivalry in LAC appear exaggerated when examined strictly through the lens of trade. Indeed, LAC is a massively heterogenous region, not least due to its North-South divide. A deeper dive into subregional and country-specific statistics suggests that China has and will struggle to meaningfully out-compete U.S. trade dominance in Mexico and Central America, given the deeply integrated North American supply chains. Similarly, the U.S. cannot realistically replace Chinese demand for South American commodities.

Nonetheless, Latin America is not free from the indirect impact of U.S.-China trade tensions. The region has been affected unevenly by them and, on balance, does not benefit from these trade tensions, contrary to some assessments. Trade diversion gains experienced by some (e.g. Brazilian soybeans and Mexican manufacturing) were offset by losses in other sectors and countries.

Notably, global demand, trade, and investment uncertainties during the height of the U.S.-China trade war (2018-2019) reinforced a downward trajectory in commodity prices (except iron ore), as well as a stagnation in volumes. In 2018, the U.S. and China levied tariffs on $403 billion worth of goods against each other, including a significant $260 billion escalation in September of that year. LAC felt the effects felt shortly after, despite a truce reached by Presidents Trump and Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the Buenos Aires G20 meeting. In 2019, the region saw the value of its exports contract by 2.4% year-on-year, and a weakening of performance in nearly every country. Copper hit a two-year low in the same year and did not significantly reverse course until 2020 (under extraordinary supply-side pressure).

In the foreseeable future, tensions will likely persist in the world’s largest bilateral trade relationship. The Trump administration held 13 rounds of formal trade talks with China before reaching the Phase One trade deal. While the Biden administration has expressed doubts about the arrangement, it has kept most of the Trump-era China tariffs in place, not least because “no negotiator walks away from leverage.” To date, average tariff rates between U.S. and China remain elevated at approximately 20%, covering over 58% of bilaterally traded goods. In parallel, as evidenced by the contentious high-level meeting in Anchorage earlier this year, U.S.-China political frictions also show no sign of letting up. This could continue to stifle meaningful bilateral exchange and coordination in other areas, including trade.

What does all this mean for Latin America and the Caribbean? A forward-looking approach would serve LAC well, as regional governments and businesses aim to better navigate the current and next stages of U.S.-China trade tensions. Here are a few key policy milestones and issues to watch on the horizon:

With regard to the U.S.

LAC should closely monitor U.S. policy actions and guidance, both explicitly and implicitly related to China. For example, the bipartisan Manufacturing Abilities Determine Economies (MADE) in the Americas Act introduced in May by Congressmen Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) and Jason Crow (D-CO) aimed to strengthen hemispheric supply chain integration and thus reduce dependency on China. This and other U.S.-led initiatives could draw greater attention to potential reshoring, nearshoring, “ally-shoring” or regional integration opportunities in LAC, a sentiment recently echoed by Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. Next year’s Summit of the Americas—the first to be hosted by the U.S. since 1994—would be a natural platform to explore and elevate these opportunities.

In addition, LAC must take steps to mitigate the possible “collateral damage” resulting from U.S.-China tensions. Firms and subsidiaries would be wise to carefully study possible licensing, review, and other requirements in the U.S., especially for those doing business with Chinese firms and individuals added to the U.S. government’s growing Entity List and sanctions list.

The potential evolution of upcoming U.S.-China discussions on the Phase One trade deal is worth tracking. As China grapples with the ambitious purchase target and the U.S. with a resurging bilateral trade deficit, the Biden administration may face domestic pressure to reengage and renegotiate the deal with Chinese counterparts. For reference, China had committed to acquire an additional $200 billion of U.S. goods by December 31, 2021 (on top of the 2017 baseline) and was 31% off target as of June 2021. Chinese efforts to ramp up purchases of U.S. goods could have implications for LAC exporters.

With regard to China

On the Chinese side, the clearest and most comprehensive policy signaling will come from the next ministerial forum between China and CELAC, which is scheduled to take place later this year. This high-level meeting is held every three years and usually accompanies the release of Beijing’s latest policy blueprint for LAC, e.g. the China-CELAC Cooperation Plan (2015-2019) during the first Forum (Beijing, 2015) and the CELAC-China Joint Action Plan (2019-2021) during the second Forum (Santiago, 2018).

Taking a longer-term view, LAC exporters should also follow developments in China outside of the policy space. Shifts in Chinese consumption patterns could bring about new opportunities, ranging from rising and vastly untapped demand in China’s massive “second-tier” cities (a dozen “mid-size” cities with more than 10 million residents) to a growing appetite for more sophisticated, gourmet consumer goods. Chilean wine and cherries, for example, have become bestsellers in the Chinese market.

For some LAC countries, product/sector-level diversification may not be immediately feasible or necessary, but diversifying markets should always be a priority to mitigate concentration risks. During the pandemic, Chinese concerns and scrutiny over coronavirus transmission through frozen food or packaging have spooked LAC exporters of Ecuadorian shrimp, Brazilian and Argentinian meat, and Chilean cherries. Chilean cherry exporters, in particular, could benefit from greater market diversification and reduced exposure to demand shocks in China, which currently accounts for over 90% of sales. Paradoxically, one smart way to diversify from China may be through China. As the Belt and Road Initiative improves connectivity infrastructure in Central and Southeast Asia, shipping costs for specific routes from LAC may lower, thus creating conditions for exports to enter new markets beyond East Asia.

—

Overall, most LAC countries do not desire or need to choose between the U.S. and China when it comes to trade. In that sense, trade wars are also a useful device for understanding LAC’s nuanced behavior and balanced position in the midst of broader China-U.S. tensions. Economically and politically, it behooves the region to work with both superpowers in respective areas of shared interests through a practical, proactive, and country-specific strategy. In the context of COVID-19 and post-COVID recovery, the region needs all the external sources of growth and support available.

—

Larraín B., former minister of finance of Chile (2010-14 and 2018-19), is professor of economics at Universidad Católica de Chile and a member of the Lancet COVID-19 Commission, the United Nations Leadership Council for Sustainable Development, and the Atlantic Council Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center’s Advisory Council.

Zhang is associate director of the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center and co-author of LAC 2025: Three Post-COVID Scenarios and China-LAC Trade 2035: Four Scenarios.