MEXICO CITY – Mexico’s president recently said he “changed his opinion.” Andrés Manuel López Obrador was referring to his campaign promise to send the military back to the barracks—one that has been left unfulfilled, as the militarization of public security has only solidified under his administration. He disbanded the federal police and replaced it with a new National Guard, now under the auspices of the Defense Ministry (Sedena) after Congress recently approved its transfer.

AMLO said he changed his mind after realizing the direness of the security scenario he had inherited—and decided that keeping the armed forces in charge would fix matters.

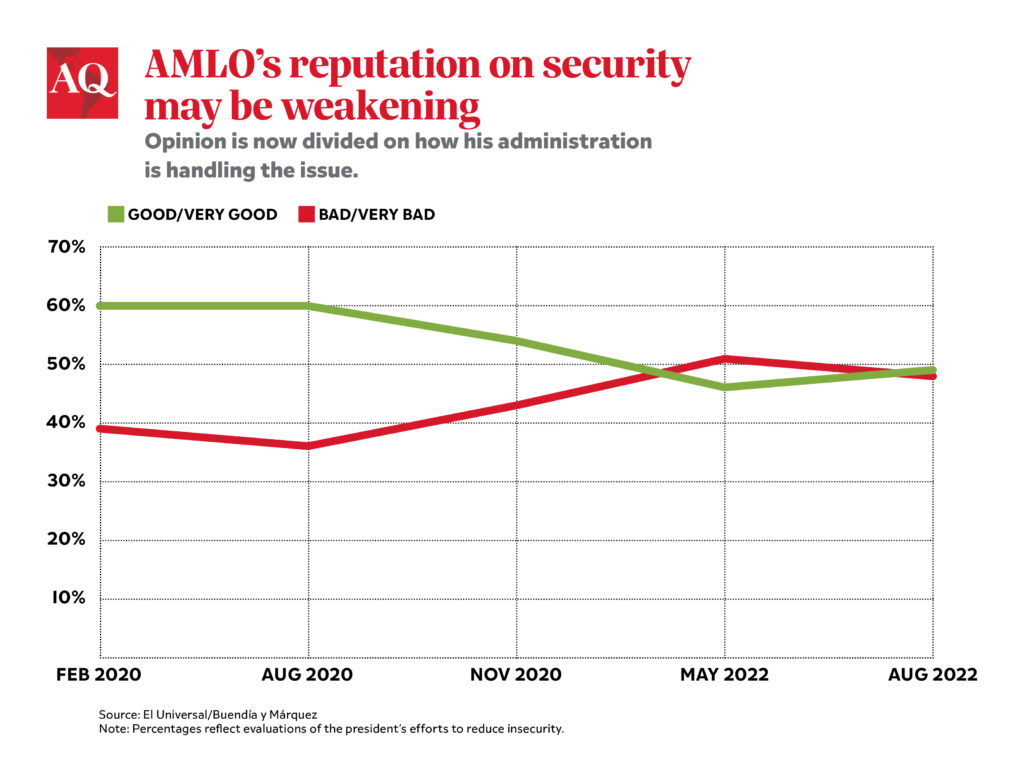

But a wealth of studies document the harm and ineffectiveness of a militarized security policy. Still, the president maintains high approval ratings and the Armed Forces continue to rank among the nation’s most trusted institutions. How can Mexico break the cycle of militarization and violence when those in power remain unpersuaded by the need for an alternative strategy?

Recent dramatic outbreaks of criminal violence have provided an eerie reminder of how Mexico’s criminal groups have learned to bully the security forces into submission, showing themselves to be in command and exposing the state’s lack of capacity to combat them. The truth is that even as AMLO’s militarized security policy has claimed scores of civilian lives, continued spectacles of violence are a compelling indictment of its failure.

A spate of violent attacks across western and northern Mexico began on August 9 when federal security forces attempted to detain a senior leader of the Jalisco Cartel New Generation (CJNG). Members of the criminal group set up roadblocks and torched dozens of stores, cars and buses to impede the arrest. From Jalisco the mayhem spread to major cities across four states, including Ciudad Juárez, where 11 innocent bystanders were murdered at random.

Four days of arson and shootings grabbed headlines in a country long accustomed to high levels of violence, as the private sector and the U.S. ambassador to Mexico voiced concern. President Andrés Manuel López Obrador ordered troops to the affected areas to reassure terrified citizens. He called the events unprecedented and regrettable—but ultimately, he dismissed them as criminal propaganda and accused his opponents of exaggerating the magnitude of the violence.

López Obrador’s administration, it seems, wants to make discretionary use of power and resources, and opts for short-term benefits over long-term gains. With the opposition weakened, it is up to citizens to oppose a failed security policy that delivers neither safety, transparency nor human rights protection. Mexicans could demand, for example, that priority be given to civilian police reform—particularly improved training, working conditions and use-of-force oversight mechanisms—and to the creation of a truly autonomous public prosecutor’s office.

Secrecy, not security

During the 2018 campaign, López Obrador also promised to pursue a policy of “hugs, not bullets.” Social programs would make disenfranchised Mexicans less susceptible to joining the ranks of organized crime. This approach might have allowed López Obrador to distance himself from his predecessors, particularly Felipe Calderón, who launched the drug war in 2006 after a narrow victory in the presidential election that López Obrador felt he had won.

But so far, “hugs, not bullets” has proved to be rhetoric, not policy. Structural transformations remain elusive as poor Mexicans remain dependent on government handouts. López Obrador has also expanded the presence, attributions and budgets of the Armed Forces, to the detriment of civilian law enforcement and criminal justice institutions. Citizens may now be at greater risk of victimization than before. Troops now take a largely permissive attitude towards the illicit armed groups and commit serious human rights abuses.

Academics and civil society groups have widely criticized the government’s embrace of militarization. Soldiers lack investigative capacity and are trained to defeat enemies, not to provide public security. There is ample evidence that this strategy has failed to slow the increase in homicides and disappearances. In fact, López Obrador’s administration is on track to conclude with the highest murder rate in Mexico’s history.

The tasks and resources that are assigned to the Armed Forces tend to be exempt from transparency obligations. At the same time, the use of the military is highly symbolic and may be interpreted as a leader’s decisiveness to act. In Mexico’s authoritarian culture, the idea that violence can defeat violence continues to resonate with many people.

Citizens need to challenge militarization

López Obrador’s mantra to put “the poor first,” and his assertion that his critics are conservative sectors who resent losing their privileges, have proved extremely powerful in a highly unequal country. Moreover, society has normalized the violence and accepted, to a large degree, the official account of the drug war. According to this narrative, those who get killed are thugs, not innocent citizens. The dehumanization of victims makes it more difficult to challenge the state’s role in the violence.

Morena, the ruling party, faces no formidable opposition and may well prevail in the 2024 presidential election. López Obrador, who favors loyalty above all else, will have a voice in selecting the party’s candidate. The two most likely contenders, Mexico City mayor Claudia Sheinbaum and Interior Secretary Adán Augusto López, are staunch allies of the president and will want to honor his legacy.

The U.S. might decide to go beyond security assistance and address its own voracious appetite for drugs and firearms, an appetite that feeds criminal markets in Mexico. It is more important, however, that citizens hold politicians accountable, at and beyond the ballot box, for the policies they enact or fail to enact.

The most persistent calls for an end to militarization and impunity have come from the families of those who have disappeared during the drug war. Relatives not only search for the missing, but also organize marches, set up anti-monuments and intervene public spaces to demand truth and justice. The huge outcry against arbitrary arrests and deaths in detention during El Salvador’s current state of exception are a reminder that victims’ families may be best positioned to lead the fight against repressive security policies. Journalists, academics and artists can do their own part to document abuses, encourage public debate and present policy proposals. But, ultimately, only broad citizen mobilization can hold governments in Mexico and elsewhere accountable to their promises.

—

Wolf is senior lecturer with the Drug Policy Program at the Center for Economic Research and Teaching (CIDE) in Mexico, author of Mano Dura: The Politics of Gang Control in El Salvador (2017) and writer and director of The Vertical Border (2022).