During my eight years as vice president, leading U.S. engagement with our partners throughout the Western Hemisphere was among the most rewarding challenges in my portfolio. Initially, progress was slow. Trust between the United States and our neighbors was at a low, driven by disagreements over the war in Iraq, the aftershocks of a great recession, a widening rift over the United States’ long-standing Cuba policy, and an overall sense in the region that we had simply lost interest.

By the time President Obama and I left the White House, we had established a new foundation of cooperation for our region built around shared responsibility, respect and partnership. It included a broader and deeper relationship with Mexico, a global agenda for cooperation with Brazil, reinvigorated engagement with Central America, post-earthquake reconstruction in Haiti, restored diplomatic ties with Cuba, support for Colombia’s historic peace process, improved energy security in the Caribbean, expanded trade and collaborative relations with countries throughout the region.

This is not to say we were perfect—far from it. Other international issues competed for our attention and entrenched challenges of poverty, violence and corruption continued to stymie growth and opportunity, particularly in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. But for the first time, it was possible to envision a hemisphere that was secure, middle class and democratic, from the northern reaches of Canada to the southern tip of Chile.

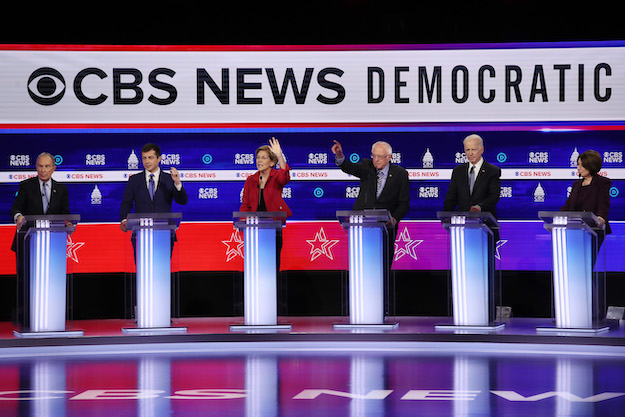

During the past two years, that foundation for cooperation has been needlessly yet determinedly destroyed. Our neighbors, including some of our closest allies and largest trading partners, have endured a torrent of antagonism from our president. Canada and Mexico have been repeatedly bullied, while Central American and Caribbean countries have been derided with derogatory epithets. The president has now twice canceled visits to Colombia, our key ally in regional security, and he has rolled back the travel and commerce that afforded Cuban entrepreneurs and families greater independence from the Communist state. The harrowing scenes we saw this past summer of children being torn from their parents’ arms at our borders will not soon be forgotten by any of our partners. And, this past April, President Trump became the first U.S. president to skip the Summit of the Americas, the premier regional forum established by the United States in 1994 to galvanize a regional agenda that corresponds with U.S. interests. In short, this administration has wantonly abdicated our leadership in the region.

Leadership Vacuum

Our disengagement comes at a time when others are stepping up in the region. China is now the largest or second-largest trading partner of virtually every country in South America’s southern cone, and the Chinese have successfully convinced the Dominican Republic, El Salvador and Panama to change their diplomatic recognition away from Taiwan. Russia too is expanding its reach throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. Our geopolitical rivals are eagerly filling the vacuum of leadership as the United States pulls back.

It is vital that we maintain our leadership role in the region—not because we fear competition, but because U.S. leadership is indispensable to addressing the persistent challenges that prevent our region from realizing its fullest potential. China and Russia seek economic and diplomatic benefits but do not invest in democratic institutions or good governance. We do, because we benefit from the success of our neighbors and we are impacted by their struggles.

If economies in Latin America aren’t growing because of corruption, if rampant violence drives people from their homes to seek safety elsewhere, or if autocrats undermine democratic institutions and abuse human rights in their countries, it affects us too. Refusing to lead—closing our border, hiding behind walls, pulling back from the region—will do nothing to help these countries address the root of these problems.

Take, for example, the problem of corruption. It’s a cancer that erodes the capacity of nations to govern, drives away crucial foreign investment and can metastasize into a crisis of legitimacy in fragile democracies. From the Panama Papers to Brazil’s “Operation Car Wash” scandal to the rampant cronyism in Venezuela and Nicaragua, we have ample evidence of how corruption undermines progress throughout the region. The people of Latin America are sick of the region’s systemic corruption.

Between 2014-2016, I visited Guatemala three times to support the work of the UN-backed anti-corruption commission in Guatemala, known as CICIG. I made it clear that U.S. funding for Guatemala hinged on CICIG being allowed to continue its work. In fact, when former Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina was subsequently arrested on corruption charges brought by CICIG, he blamed me. Our administration’s support—and intense personal engagement with regional leaders—was critical. For the first time, the people of Guatemala began to feel like no one was above the law.

Yet in August of 2018, when President Jimmy Morales announced that he would not renew CICIG’s mandate—flanked by military leadership, with U.S.-donated Army vehicles posted in a show of force outside CICIG’s headquarters and the U.S. Embassy—Secretary of State Pompeo called Morales to tell him that the United States supported Guatemala. There could not have been a clearer message to kleptocrats throughout the region that the United States is no longer in the anti-corruption business. That hurts all of us.

Security Requires Respect

Consider also the difficult question of migration, particularly from Central America, where so many are fleeing crime, violence, persecution and a lack of opportunity. Securing our borders, enforcing our immigration laws, and fulfilling our humanitarian obligations is a challenging mandate, but we can—and we must—do all three at once.

In the summer of 2014, President Obama asked me to lead our response when an estimated 68,000 unaccompanied minors came across the border.

Rather than implementing draconian policies or tear-gassing civilians, we worked closely with Congress to help the Central American governments address the root causes pushing people from their homes. We put together a $750 million program to help them combat corruption and human trafficking while increasing domestic revenue and tax collection—and we made our assistance conditional on results. During our final years at the White House, Honduras overhauled its police force to root out widespread corruption, Guatemala collected hundreds of millions of dollars from tax-evading companies and expanded cooperation between our transnational anti-gang units and Central American law enforcement resulted in successful operations like the May 2015 indictment of 37 members of the street gang MS-13 in Charlotte, North Carolina.

These are serious challenges that impact the security of U.S. citizens. They require serious and thoughtful leadership. Scapegoating immigrants may offer the hope of short-term political gain, but it doesn’t solve the problems or prevent more migrants from attempting to reach the United States. We need policies that reflect the heart and the dignity of our nation—policies that uphold our laws and the sanctity of our borders, as well as our international humanitarian obligations. We also need to invest the political capital necessary to reform our broken immigration system.

Finally, the United States needs to be an active partner to defend the democratic character of our region. This has been a persistent challenge—one the United States has not always risen to—but with the tides of nationalism and populism rising once more throughout the region, and growing threats from autocrats and their henchmen, principled U.S. leadership is needed more than ever.

Instead of respecting the will of their people, the governments of Nicolás Maduro in Venezuela and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua have confronted peaceful protesters with force, even armed vigilantes. They have limited the freedoms of expression and assembly necessary for political dialogue and arrested their political opponents. In Venezuela, government officials have embezzled billions of dollars from government coffers, while everyday citizens struggle to find food and medicine. It is an affront to democratic values.

Yet, even sensible efforts by this administration to exert pressure on Maduro and Ortega have been undermined by politicization, faulty execution and clunky sloganeering. Stronger diplomatic efforts and intensified sanctions on Venezuela have been clouded by saber-rattling and misguided efforts to engage with coup plotters. Similar responses to the civil unrest and state repression earlier this year in Nicaragua produced little in the way of results as that country settles into an intolerable “new normal.” This administration has demonstrated its willingness to capitalize politically on crises, but actions like its continued deportation of Venezuelans and the attempted revocation of “temporary protected status” for Nicaraguans demonstrate little concern for the Venezuelan or Nicaraguan people.

Governments have a basic responsibility to respect the universal rights of their citizens. Our region embraces that precept in the Inter-American Democratic Charter—that means that all the countries of this hemisphere, including the United States and our friends and adversaries alike, have a duty to support the people of these countries. All our citizens want the same basic things: a job that pays a fair wage and puts food on the table, education for our children, security for our families, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, a sense of opportunity and the hope that tomorrow will be better than today. The region used to look to the United States on such matters. But if we tarnish our example, we must expect that they will look elsewhere.

Resilient Ties

The breakdown of U.S.-Latin American relations in such a short time is striking, but it is not beyond repair. The shared values and history that bind the U.S. together with Latin America and the Caribbean—as well as Canada—have proven durable and resilient through many missteps and recalibrations. But steps need to be taken—and soon—to ensure that the current breach does not deepen into a divide that damages U.S. relations with the hemisphere for a generation.

We need to ensure U.S. leadership continues to be a driving force for positive regional change that will enable all of our countries to prosper and grow. We must pursue the opportunities afforded by greater energy integration, continue to combat the scourge of corruption and share the benefits of trade more broadly, enhance our shared security and rebuild multilateral cooperation in the hemisphere. And we must make sure that when the next Summit of the Americas convenes in 2021, there will be a U.S. president at the table, ready to lead our region toward the future all our peoples deserve.

—

Editor’s note: Americas Quarterly has invited the Trump administration to comment on its Latin America policy, and hopes to publish their contribution soon in print and online.