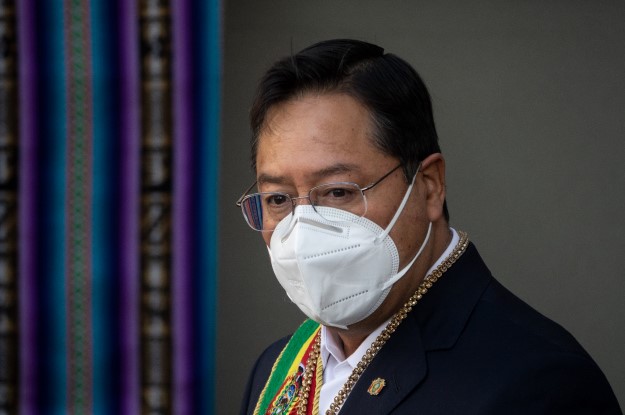

LA PAZ – When Luis Arce took office as Bolivia’s president last November, he promised to “rebuild the country in unity” after years of divisive politics. He signaled a willingness to build bridges between his party — Evo Morales’ Movement toward Socialism (MAS) — and its opponents, a year after Morales had resigned from the presidency amid bitter unrest and accusations of fraud.

Unfortunately, a series of actions, most recently the arrest of former interim President Jeanine Áñez and two of her former ministers, have cooled hopes that Arce might be a moderating force in Bolivian politics. The arrests came less than a week after MAS performed poorly in local elections and a month after Arce issued a controversial decree granting amnesty to individuals accused of committing crimes in protest of Áñez’s transitory government.

Áñez was arrested on March 14 as part of a case against military and police officials accused of fomenting a coup against Morales. She is accused of sedition, terrorism and conspiracy — charges Áñez described as “political persecution.” The international community raised concerns that due process was not being respected. Jose Miguel Vivanco, the Americas head at Human Rights Watch, tweeted that the order to detain Áñez and her ministers “contains no evidence whatsoever that they have committed the crime of terrorism” and “raised doubts that the case was based on political motives.” He added that this is “a sad spectacle of political persecution.”

Áñez took office after Morales fled Bolivia in 2019 following three weeks of massive protests in response to fraud allegations that spread following the presidential election. Congress, controlled by Morales’ party, annulled those elections, and the Supreme Court, also dominated by Morales sympathizers, confirmed Áñez’s ascension to interim president as next in the line of succession, following a series of resignations. Her government quickly began a campaign to target her opposition, issuing terrorism charges against Morales — charges similar to ones she now faces.

Many thought Arce, who was elected in a landslide in October, might avoid going after the opposition as aggressively as his predecessors had. Early into his presidency, it appeared that the respected technocrat was taking a more moderate approach to governing, following his measured language during the campaign and the selection of David Choquehuanca, a moderate indigenous leader, as his vice president. In December, Arce presented a judicial reform — encouraging news from a president whose party for years had eroded judicial independence by handpicking judges and prosecutors.

Those hopes have now faded. The judicial reform, for one, was shelved 100 days into Arce’s government. The president had supported the creation of an independent council of legal experts that would design a broad reform bill. The MAS-majority Congress, however, discarded the plan, and neither Arce nor his justice minister, Iván Lima, pushed back.

Arce, meanwhile, issued an executive order in February, later sanctioned by the MAS majority in Congress, which pardoned some 1,000 people accused during the transitional government of various crimes committed in support of the MAS or in protest of Áñez’s government. These included individuals accused of shooting anti-MAS demonstrators, burning the homes of a journalist and a human rights defender, destroying 64 public buses in La Paz, and dynamiting hills to force the closure of roads.

“They accuse their adversaries while they pardon their own,” said historian Robert Brockmann.

Arce’s decree opened the door to impunity for supporters of the ruling party, Human Rights Watch warned.

“There is strong evidence indicating the previous government persecuted MAS supporters in politically motivated cases,” added Vivanco. “But granting a blanket amnesty to MAS supporters without clear criteria undermines victims’ access to justice and violates the fundamental principle of equality before the law.”

Also concerning is an apparent purge of public servants within the international relations ministry and Central Bank. Since Arce’s inauguration, Foreign Minister Rogelio Mayta has ordered the unprecedented dismissal of 90% of the ministry, according to a group of former employees. Even military regimes of the sixties and seventies respected diplomats’ careers. At the Central Bank, a technical entity, a majority of the senior management has been fired.

Furthermore, Arce issued another executive order in March requiring aspiring public administration employees to go through a “decolonizing and depatriarchalizing community social service” and be vetted by a group of social organizations. Critics say this is nothing more than a way to ensure that all civil servants come from the governing party’s ranks.

“There is an onslaught on all sides,” said analyst Walter Guevara, a renowned Bolivian intellectual. “There is very strong pressure from the authorities undermining the rule of law in Bolivia.”

Vengeful politics have not worked so far for Arce’s government. On March 7, MAS performed poorly in regional elections, and while final results are pending, the party is on track to register its worst performance since 2005. While MAS is still Bolivia’s strongest party, and the only one with national scope, it now only controls two of Bolivia’s 10 main cities. Morales, who oversaw the selection of his party’s candidates, had discarded some for reasons of personal animosity. Several of those leaders ended up winning the elections as candidates of other parties. It is also possible that the hostile actions by Arce’s government against his opponents strengthened some of the anti-MAS candidates, like Iván Arias, who was elected mayor of La Paz.

Arce faces, therefore, a complicated situation. First, his party has had a significant electoral setback. Second, his relationship with Morales, the real force behind the party, seems strained, demonstrated by the few times they have met and mentioned each other in recent months. Third, slow and ineffective vaccination and pandemic containment plans are facing public criticism. Finally, the economy remains stagnant and authorities have not approved measures needed to reactivate the private sector.

Such a situation of apparent weakness helps explain the government’s aggressive actions against its adversaries, said Hernán Terrazas, a political analyst.

“There are already calls from some mid-level MAS party leaders for the return to cabinet posts of figures characterized by heavily authoritarian positions,” he said.

Few anticipated that in such a short time, Arce’s government could look more worrying than Morales’. But less than five months in, it is increasingly hard to deny that this is the case.

—

Peñaranda is a Bolivian journalist and director of the Brújula Digital news portal. In 2015 he won the Maria Moors Cabot Award, awarded by Columbia University.