SANTIAGO – When millions of Chileans took to the streets in October 2019, after a small hike in transport fees quickly morphed into a national movement for political change, it seemed that Chile’s populist moment had finally arrived. Alongside protesters’ demands for better healthcare and pensions were sentiments that populists around the world would recognize: A strong current of anti-elitism, demands for institutional change, and a mistrust of existing political parties. Yet one thing seemed to be missing: A strong and personalistic leader who could channel those populist inclinations and put them into practice.

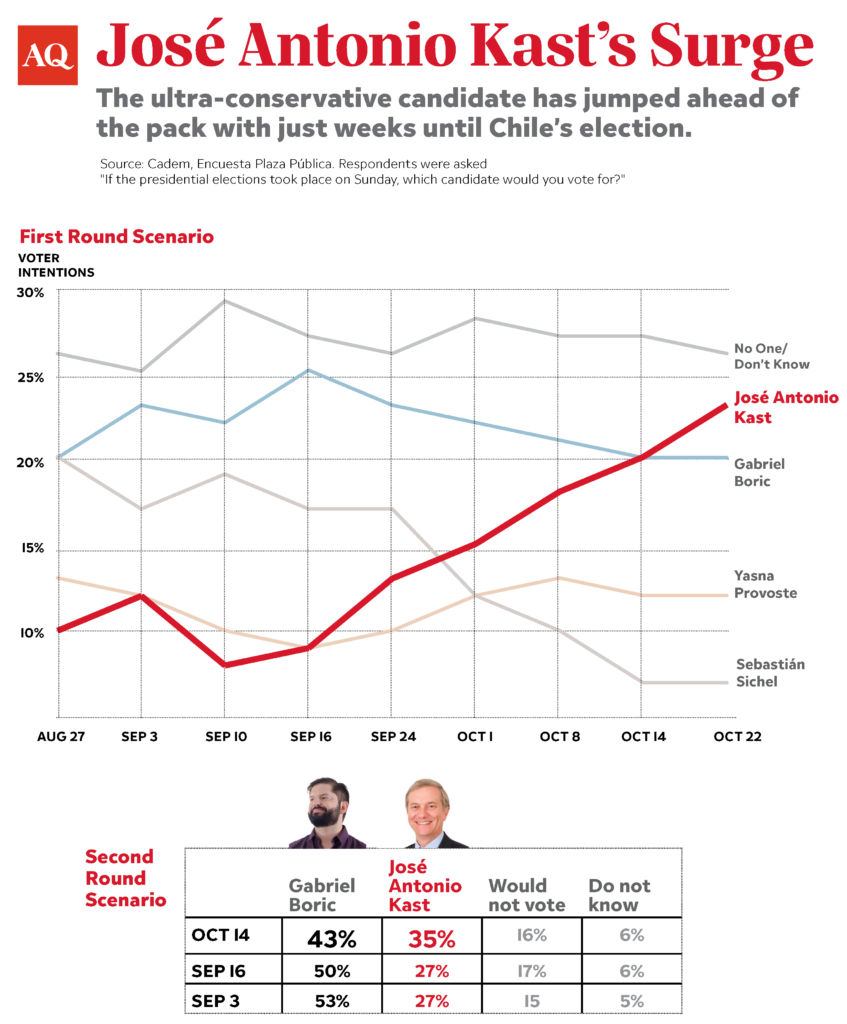

That may now be changing. As Chile’s November 21 election quickly approaches, the presidential race has been upended by the meteoric rise of the far-right José Antonio Kast, a former congressman once seen as a fringe candidate, but who now leads at least one major poll and is second in others. While polls suggest the Kast would lose in a runoff to leftist front-runner Gabriel Boric, the race has tightened substantially in recent weeks, according to Cadem. Behind Kast’s rise: a backlash against politics as usual, strong rhetoric against immigrants, and his ability to channel the simmering anger of Chile’s middle class. Indeed, he could be described as the true populist in the race.

Many observers had assumed a populist figure would come from the Chilean left. But Boric, a congressman who represents a coalition of forces that see themselves as representative of the spirit of the 2019 protests, has for the most part avoided descending into populism. He emphasizes the importance of respecting democratic institutions, and unlike many on the left, he is a vocal critic of the Venezuelan, Nicaraguan and Cuban regimes. He supported a November 2019 cross-party agreement aimed at rewriting Chile’s constitution, something his Communist coalition partners rejected.

To be sure, there is a touch of populism in the campaign’s fetishization of lo popular. And in a recent interview, Boric’s economic advisor admitted that a policy the candidate has supported (successive withdrawals from private pension funds) is bad public policy and terrible economics, but that “he’s doing something reasonable for someone who’s in politics, which is to respond to what people want.”

But does Boric really know what people want? The tattooed 35-year-old candidate is betting on Chile being as woke as he and his coalition buddies are. On a whole range of campaign issues, they engage in the language of today’s progressive left. From foreign policy to education, his election platform promises to be feminist, green, anti-racist, participatory and decentralized. The constitutional convention has committed to gender neutral language and a rule forbidding denialism, which severely limits the scope of discussion. Those who deny, for example, that the 2019 protests involved systemic human rights abuses (an open question) could be subject to re-education programs (Article 45 of the Convention’s Ethics Regulations states that the “programs will be geared towards training in the area infringed, such as human rights, intercultural relations, gender equality, religious or spiritual diversity, or any other that is required”).

Chile’s efforts to make strides towards a more inclusive society should be applauded, especially if they avoid falling into us-vs-them populism or authoritarian efforts to “reprogram” offenders. Such efforts are also not especially unusual, as Chile’s economic progress has pushed it closer towards the post-material attitudes common in Western democracies. For years now, polls have shown Chileans to be increasingly liberal on a range of values, and this is especially true among the young – the kind of voters Boric hopes to attract.

However, while these values are common among highly educated young people, they are resisted by other sectors of society. Widespread access to tertiary education is relatively new in Chile, so a good part of the highly educated cohort in Chile is under 40. But many older, less educated or rural voters view progressive values not only as elitist but also morally objectionable, reflecting trends in other countries that have lurched toward populism, as Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart have noted.

And so it is that Kast has come to lead polls, four years after finishing fourth in the 2017 presidential race with just 8% of the votes. Since then, Kast founded his own party, the Republican Party, frustrated by what he saw as the failure of the right-wing UDI party to defend the legacy of the Pinochet dictatorship with sufficient enthusiasm. In recent weeks he has supplanted the traditional right’s chosen candidate Sebastián Sichel, who, with origins in the Christian Democratic Party, had hoped to capture disaffected centrist voters. He failed, and the traditional right returned to its natural candidate and political space: conservativism, corporatism and a dogged defense of Pinochet’s constitution.

But this is 2021, and this is not your grandparents’ pinochetismo. Kast criticizes immigration, downplays the demands of the country’s indigenous communities, and promises to combat “gender ideology.” His campaign promises measures to promote “natural methods” of contraception and to involve Christian churches in dealing with alcohol and drug addiction. On the international front, Kast, who is close to Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, questions “globalism” and sees the United Nations as a tool of the left, often blaming it for Chile’s immigration problem. He promises to withdraw Chile from the UN Human Rights Council. He also plans to build “physical barriers” between Chile and its northern neighbors. Kast, then, is a pretty good representative of the new, nationalist, populist right. And while not especially charismatic, he does seem to embody, far more than Boric, the anger and frustration of a middle class that feels represented neither by unresponsive parties and institutions, nor by the new, progressive Chile being celebrated in the constitutional convention.

Kast’s success thus far shows that the assumptions about the 2019 protests have been, if not exactly wrong, then insufficient. More than a peaceful movement for political change, the protests were always more about anger and frustration and rejecting traditional political parties and leaderships. This why a constitutional agreement – aimed at redesigning those institutions – was understood to be the only way out at the time. And this is why the far right may be as close as the far left to capitalizing on the current political moment.

—

Funk is professor of political science at the University of Chile and a partner in Andes Risk Group, a political consultancy firm.