This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on Lula and Latin America | Leer en español | Ler em português

Listen to this story read by the author by clicking the play button above.

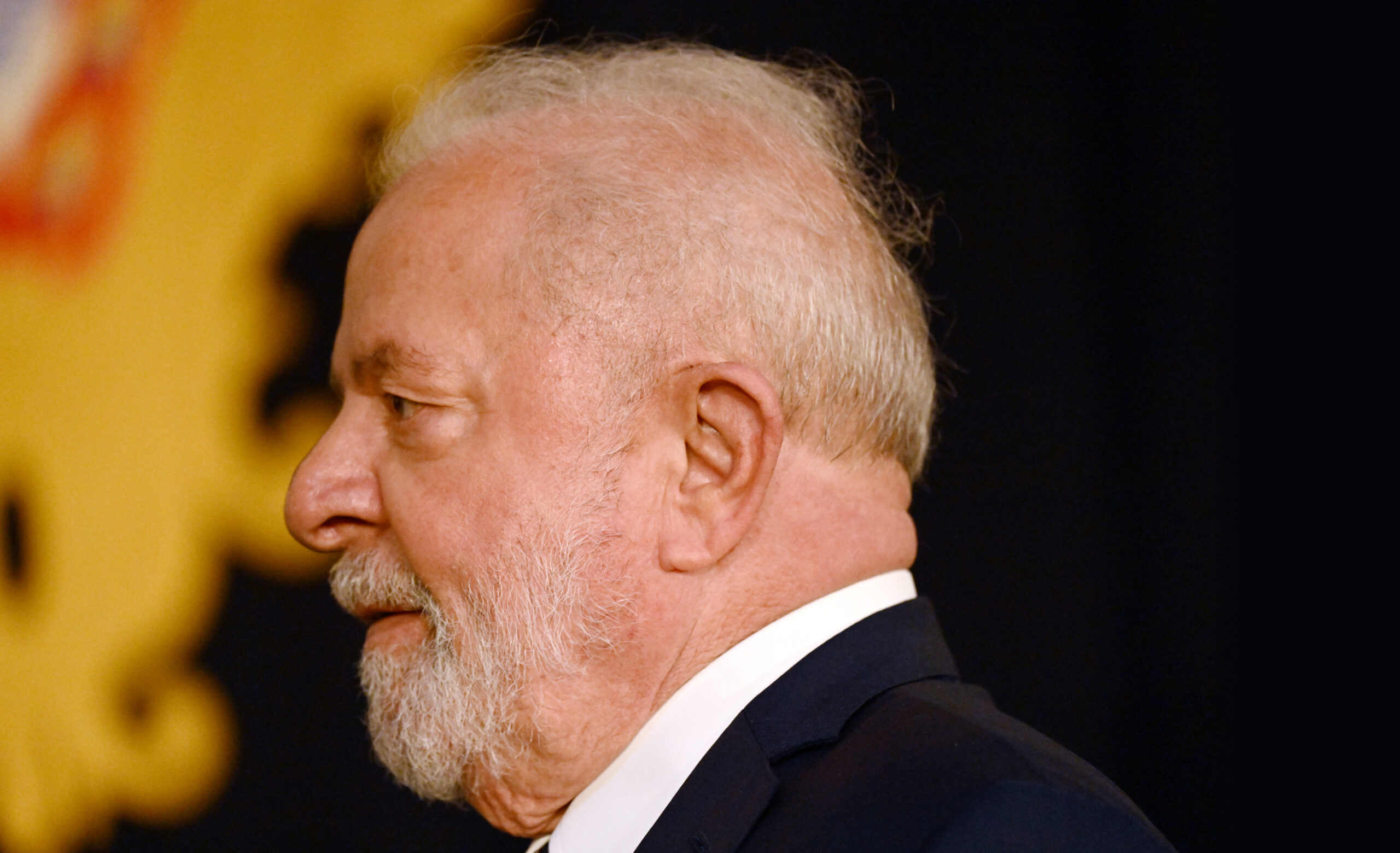

SÃO PAULO — “Brazil is back,” President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva told a roaring crowd at the climate summit COP27 in Egypt in November last year.

Indeed, during his first few months in office, Lula met or spoke to numerous leaders from across the world and announced intercontinental trips for practically every upcoming month, signaling that he would seek to significantly increase Brazil’s diplomatic footprint and re-engage on a host of issues ranging from the fight against deforestation and climate change to strengthening multilateralism and weighing in — at times controversially — on the war in Ukraine. Brazil’s rediscovered global activism goes beyond presidential diplomacy. Cabinet members are zigzagging the globe, seeking to present the new Brazil. Environment Minister Marina Silva has readily embraced climate diplomacy, spoke at the World Economic Forum in Davos and recently met U.S. climate envoy John Kerry, while Foreign Minister Mauro Vieira carried the message that Brazil sought to play a greater role at the recent Munich Security Conference and the Raisina Dialogue in Delhi.

Yet the question remains: What does Lula’s return really mean for Latin America and questions like regional trade integration, the region’s relationships with the United States and China, investment flows, and Latin America’s overall role in the world? At first sight, nowhere is the change of guard in Brasília bound to have a greater impact than in Brazil’s neighborhood, a region that has been adrift for years, without a leader willing or capable of setting the agenda of the regional debate, articulating a vision or claiming a regional leadership role.

There are numerous reasons that suggest Brazil’s new president may be uniquely well-placed to take the reins and exercise regional leadership and have a tangible impact on Latin American affairs. First of all, in a region where all democratically elected leaders are relatively inexperienced first-term presidents, a reflection of the profound anti-incumbency wave that has reliably thrown out the governing party over the past years, Lula stands out. Having governed Latin America’s largest country from 2003 to 2010, he is the region’s only diplomatic heavy hitter and the most globally visible Latin American political leader of his generation.

Secondly, the president seems genuinely interested in seeking closer ties to Brazil’s Latin American neighbors. Lula’s decision to skip the World Economic Forum in Davos and travel to Buenos Aires instead to join the summit for the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) was rich in symbolism. It reflected a palpable commitment to overcoming the deep divisions that had emerged over the past years, as former President Jair Bolsonaro had made little effort to hide his dislike of the emerging wave of leftist leaders. Bolsonaro’s non-existent personal relationship with his Argentine counterpart—the two barely ever spoke—produced the worst crisis in bilateral ties between South America’s largest countries since the 1980s.

Lula enjoys another advantage: His return to power coincides with what several analysts have dubbed the “second pink tide” of left-wing leaders across Latin America, a region where meaningful progress in deepening cooperation has historically depended on ideological alignment. With virtually all major Latin American countries led by leftists, Brazil’s new president seems to have, at first sight, a rare window of opportunity to not only reestablish a dialogue, but also make bolder moves to help the region overcome its numerous challenges.

Furthermore, in an increasingly turbulent world shaped by the return of great power politics, Brazil remains far from all major geopolitical flashpoints. Latin America is today the region with one of the lowest risks of interstate war or large-scale geopolitical tensions, making it attractive for investors who seek to protect their portfolios from potential geopolitical shocks. In addition, shifting global supply chains and Washington’s attempts to reduce its economic dependence on China represent a historic opportunity for Brazil, and Latin America as a whole, to attract U.S. investments, while retaining its attractiveness for investors from elsewhere.

Provided that Brazil manages to significantly reduce the rate of deforestation—which is admittedly an “if”—Lula will possess ample space to project Brazil as part of the solution, rather than part of the problem, to one of the world’s most pressing challenges. Lula’s diplomatic influence could easily increase in other areas, too, helping Brazil regain the global stature it achieved in the late 2000s. Finally, Brazil remains one of the few countries in the world that seems, at least in principle, capable of walking the talk of non-alignment: No other country is both a BRICS and a G20 member, while also taking significant steps towards joining the OECD. While the Brazilian government’s ambition to play a mediating role in the Ukraine war seems unrealistic — and his comments on the topic during a trip to China were not well-received in Europe and the United States— it does provide the Lula government with a seat at many different tables.

Key challenges

Yet while Lula’s Brazil no doubt enjoys diplomatic advantages that provide him with an opening in Latin America, the country also faces a number of significant obstacles to playing a more visible international role.

Five issues stand out.

First of all, just like many other Latin American countries, Brazil’s domestic politics remain fragile and extremely polarized following the 2022 election, the closest in the nation’s modern democratic history. Economic growth projections for 2023 are dismal and range from 0.2% to 1.2%—nowhere near the figures needed to assure political stability. Lula’s decision to criticize Central Bank Governor Roberto Campos Neto for keeping interest rates excessively high reflects the government’s expectation that patience among numerous voters is likely to run out well before the economy will recover, requiring a scapegoat and a narrative that someone other than Lula is to be blamed for what almost inevitably looks like a lackluster economic performance during the president’s first year in office.

While predicting political upheaval is difficult, it seems likely that Lula’s approval ratings will fall toward the end of the year, particularly if the outlook for 2024 remains pessimistic—the IMF currently predicts a meager 1.5% growth for Brazil in the coming year. GDP per capita in 2022 is practically the same as in 2011, which makes the past 10 years far worse than the “lost decade” of the 1980s. While even solid economic growth cannot guarantee political stability—as the wave of protests in 2019 in Chile and the current political crisis in Peru show—the absence of it significantly elevates the risk of domestic instability, which generally makes an ambitious foreign policy more difficult. Lula’s promise that “Brazil is back” on the global stage is only sustainable in the medium term if the government succeeds in pulling the country out of its decade-long economic stagnation, which forced all Brazilian presidents since 2013 to face the specter of impeachment. The strength of the opposition also explains why Lula is very unlikely to move forward with a more modern approach to fighting drug trafficking, as seen in Uruguay, which has legalized cannabis and now legally exports the product to the United States. Conservative state governors will assure that Brazil’s heavy-handed approach will continue, assuring a large prison population, a boon to cartels that need to constantly recruit vulnerable youth. Contrary to Uruguay or, more recently Colombia, Brazil is unlikely to be on the forefront of the debate about rethinking the war on drugs.

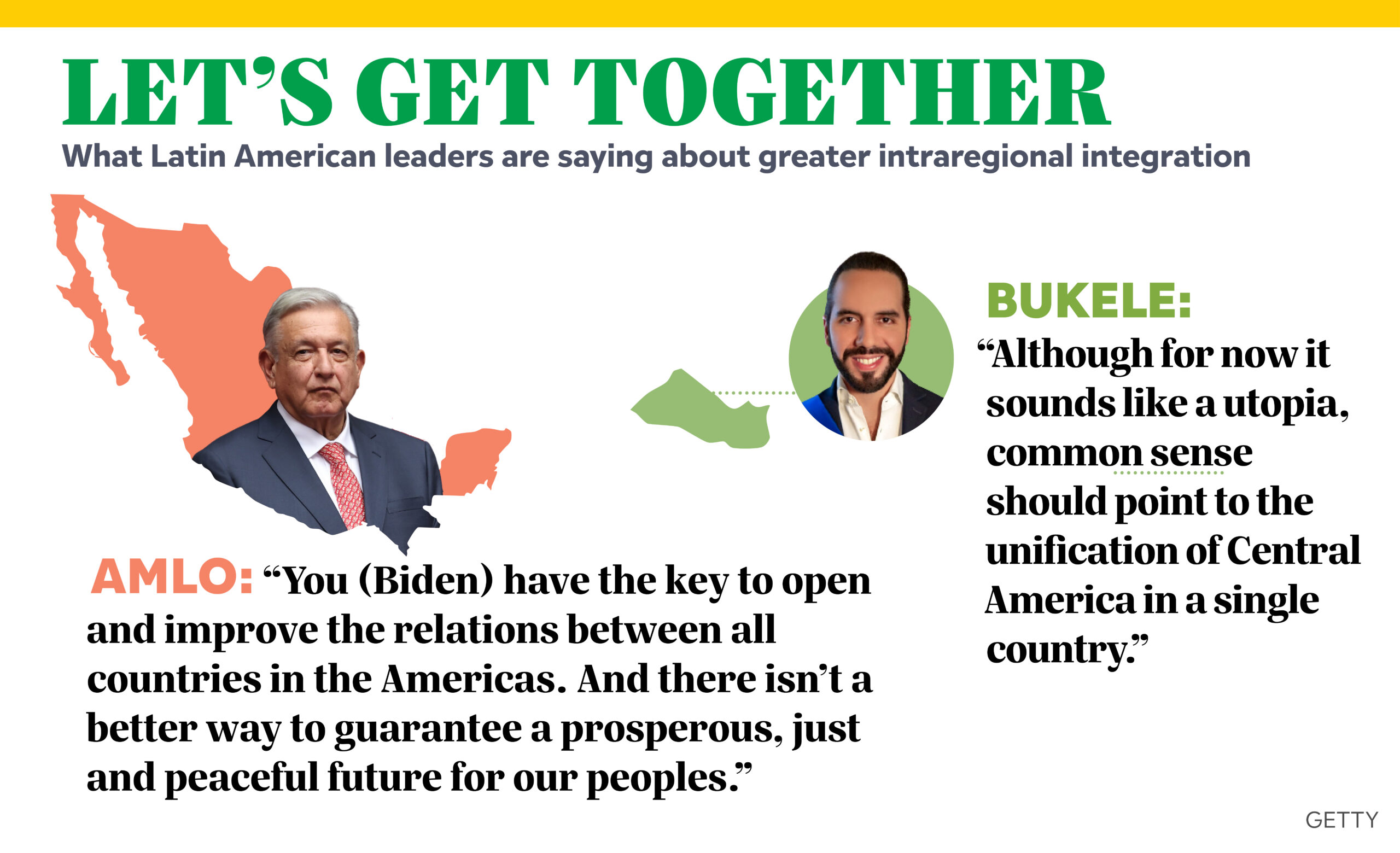

Secondly, while the new pink tide no doubt facilitated Lula’s quest to normalize its relationship with other Latin American leaders—which he has already largely achieved since returning to office—the differences among leftist leaders and their views about Latin American affairs are profound. While leaders like Nicaragua’s Ortega and Venezuela’s Maduro are social conservatives with messianic tendencies and authoritarian records, Chile’s Gabriel Boric is a European-style social democrat and progressive, a difference that has predictably led to tensions between Santiago, Managua and Caracas. It would be difficult to imagine Boric and Mexico’s López Obrador, for example, agreeing on much regarding regional integration, no matter what kind of narrative Lula seeks to promote. The duration of the second pink tide, moreover, is set to be far shorter than that of the 2000s. Indeed, chances are that by the end of 2023, a center-right or far-right government will come to power in Argentina, potentially limiting the space for deepening bilateral ties.

Third, while the Brazilian government would never explicitly claim to be a regional leader, there is no doubt that part of its claim to have a seat at the table of the powerful—be it at the BRICS, G20 or the UN Security Council, where the country continues to seek permanent representation—is its capacity to represent its region. Yet interestingly enough, while Brazil’s more assertive role is almost unanimously welcomed around the world — despite recent friction between Brazil and NATO over Lula’s insistence that the West was incentivizing the continuation of the war —, its leadership ambitions often receive a far cooler reception in Latin America. While the majority of governments in Latin America are happy to see the back of Bolsonaro, many remember Lula’s regional policy back in the 2000s as somewhat grating. Others complained that back then, both Lula and his roving foreign minister Celso Amorim felt more at ease on the global stage than when trying to address regional issues, such as the years-long spat between Uruguay and Argentina over a paper mill that began in 2005, when Brazil had a notably standoffish posture. Former Colombian officials who dealt with the Lula government in the 2000s do little to hide their criticism of Brazil’s refusal to play a more supportive role in Colombia’s fight against the FARC insurgency— for example by keeping FARC fighters from using Brazilian territory to evade Colombian soldiers. In Central America and the Caribbean, Brazil’s influence is so limited that its capacity to take a leading role in addressing the region’s main challenges—such as organized crime and migration—is low.

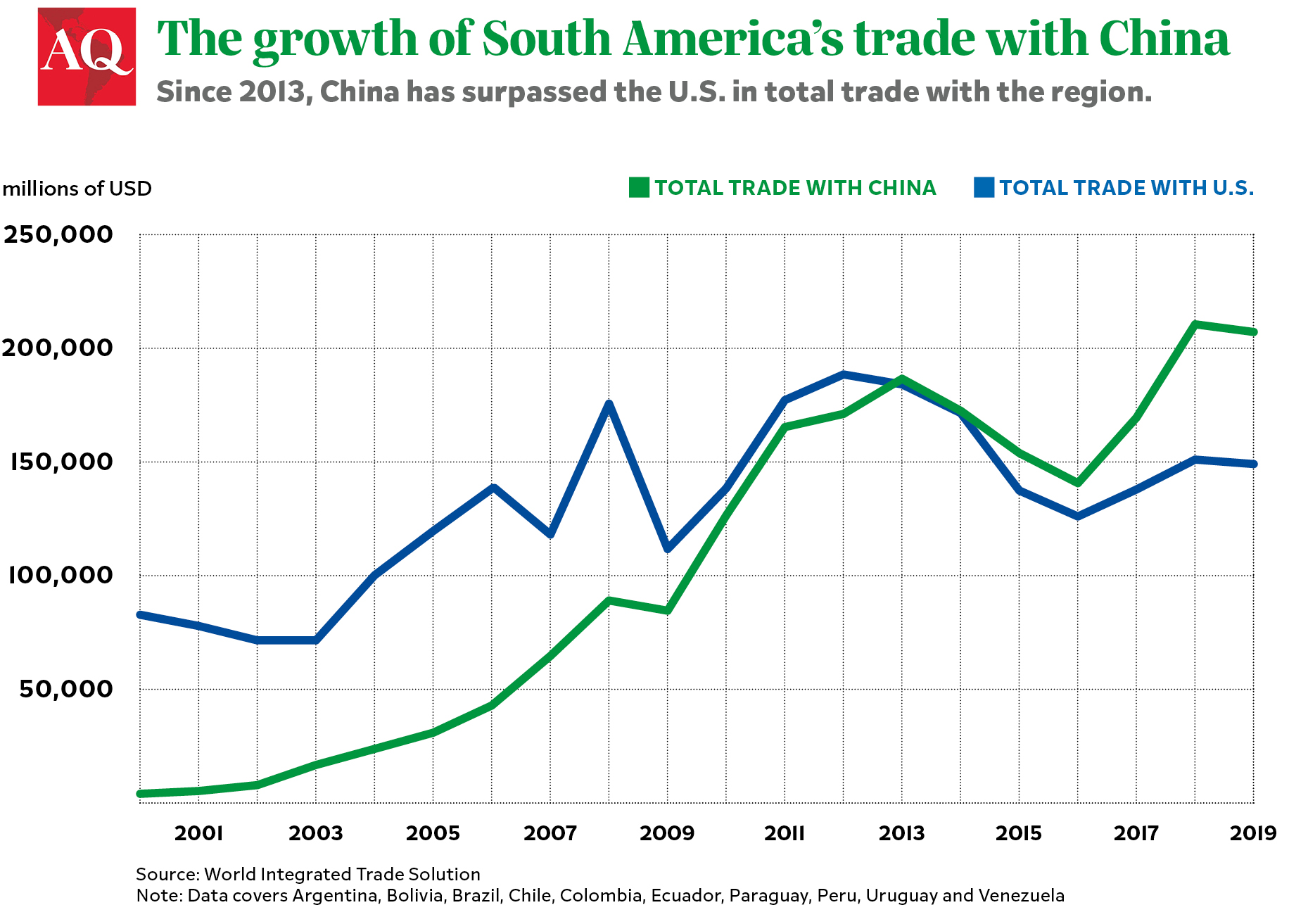

Fourth, the space for broader change or deeper regional integration remains far more limited than when Lula was first president. Truth be told, regional disintegration has been the most dominant economic trend in Latin America over the past decade. The decline of manufacturing, the growing lack of economic complementarity, the rise of China, and Latin America’s growing dependence on commodity exports explain why regional trade is far less important today than in the past. In 2021, intra-regional exports amounted to only 13% of Latin American countries’ total exports, down from over 20% in the late 2000s. Uruguay’s growing impatience with Mercosur and Montevideo’s willingness to negotiate a trade deal with China are a reflection of this structural trend Lula will be unable to alter. While Brazil’s large construction firms in the 2000s actively called for more regional integration—eyeing large-scale public contracts in countries like Venezuela and Peru—nowadays the captains of Brazil’s economy, particularly in agribusiness, are less interested in the matter.

This shift became particularly evident in the aftermath of Bolsonaro’s victory in 2018, when the incoming Economy Minister Paulo Guedes, in an interview, spoke disparagingly about Mercosur and characterized it as dispensable. Twenty years earlier, such a comment would have caused alarm among Brazilian CEOs, but this time, the loudest criticism came from retired 1990s-era diplomats without political power. In a difficult political environment where picking the right battles is crucial, Lula may think twice before tackling an issue that seems to be losing political relevance in Brazil’s domestic debate. At no stage over the past decades was Latin America less economically relevant to Brazil than it is today, and if current global trends are any indicator, Brazil’s dependence on economic partners outside of Latin America will only increase. This trend will be aggravated by the long-term (and probably irreversible) trend of deindustrialization in Brazil, which makes the region—which bought many value-added goods from Brazil—less relevant.

Fifth, the number of political crises across Latin America continues to make something as simple as a regional summit with all heads of state difficult to accomplish, as the recent summit of the CELAC in Buenos Aires revealed. Three heads of state overseeing systematic human rights abuses in their respective countries—Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro, El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele and Nicaragua’s Daniel Ortega — did not bother to show up. Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, host of the previous CELAC summit, also decided against traveling to Argentina.

Compared to the emergence of a remarkable normative framework across Latin America to safeguard democracy in the 1990s and early 2000s—such as the Inter-American Democratic Charter, signed in 2001—nowadays few presidents in the region are willing to criticize other governments’ domestic violations unless it helps them mobilize their supporters at home. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, the region recorded the biggest democratic recession of any region over the past 20 years. One of the root causes is no doubt that numerous Latin American economies have been lagging behind emerging markets elsewhere for years. Several key economic indicators such as poverty levels and inequality are now worse than a decade ago, leading to a reversal of expectations generated during the commodity boom and elevating the risk for political upheaval.

In addition to large-scale protests and severe political instability in Peru, a political crisis has gripped neighboring Ecuador. Haiti seems unlikely to emerge from non-stop political turmoil, and repression in non-democratic regimes in Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua shows no sign of abating. Given such a convoluted set of problems, Lula’s capacity to exercise regional leadership is set to be limited. To make matters worse, Lula is constrained by the leftist wing of his party that so emphatically sides with the governments of Cuba, Nicaragua and Venezuela that Brazilian diplomacy has, out of fear of confronting the Workers’ Party’s most loyal followers, opted to take a back seat in the debate about the crises in the three countries. That is hardly an encouraging sign for those who expected Lula to become an agenda setter in regional affairs.

Lula’s foreign policy legacy

None of this means that Lula’s return will be of little consequence to Latin America—quite the opposite. Irrespective of whether one agrees with the Brazilian president’s foreign policy views, there is no doubt that Latin America’s visibility in geopolitical debates is set to increase markedly over the years to come. In some cases, this is welcome news: Without Latin America at the table, the global debate about how to combat deforestation and climate change cannot advance.

Yet international observers tend to overlook the formidable challenges Lula faces both internally and in the region: severe polarization, low economic growth and the specter of falling approval ratings are set to limit the time and energy the president can dedicate to regional integration.

In addition, with Brazil’s movers and shakers increasingly disinterested in regional affairs, and a government aware that it must pick its battles wisely, the foreign policy legacy of Lula’s third term is likely to be less about Latin America and more about general reengagement after the Bolsonaro years. That means, specifically, a possible ratification of the trade deal with the European Union, a possible trade deal with China, and the emergence of Brazil as a global climate superpower — but perhaps not a return to the heady talk of a more unified, ascendant Latin America.

Listen to this episode of The Americas Quarterly Podcast for more on Lula’s foreign policy