This article is adapted from AQ’s special report on the Trump Doctrine

BOGOTÁ— Peace remains one of Colombia’s biggest yet most elusive goals. Nearly a decade after the country signed its landmark Peace Accord with the FARC, Colombia still stands at a crossroads. The 2016 vote on the agreement exposed deep national divisions, and political polarization has shaped every step of its implementation. The result is a peace process simultaneously hailed abroad as a global model and criticized at home for falling far short of expectations.

From the beginning, the accord has been trapped in political turmoil.

After five years of negotiations in Havana, the administration of President Juan Manuel Santos reached an agreement in 2016 with the oldest guerrilla group in the Western Hemisphere, which had been fighting the Colombian state for more than half a century. After the historic accord, a national referendum was called to seek the people’s approval. On October 2 of that year, Colombians went to the polls to answer the question: “Do you support the Final Agreement to End the Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace?” Against all odds, the “No” vote prevailed with 50.2%.

Following the rejection of the plebiscite, a renegotiated version was adopted, incorporating most demands from opponents led by former President Álvaro Uribe. In early 2017, roughly 13,000 combatants came out of the jungle and Colombia’s most remote regions to demobilize and surrender their weapons.

Yet the agreement broke down over two flashpoints that struck at the heart of public unease: how the FARC would be judged and punished, and the guarantee of 10 congressional seats for its leaders over two consecutive terms, ending in 2026, without the need to win them at the ballot box. To former president Uribe and his supporters, the deal crossed a red line. A guerrilla group blamed for kidnappings, massacres, forced displacement, and countless war crimes, they argued, could not be ushered into power without punishment. Their rallying cry was prison for perpetrators and zero political rights.

But that hard line would have sunk the accord. For the FARC, accepting it would have meant capitulation—and the stripping away of the political causes they said had driven their historic armed struggle.

The justice framework agreed upon was a complex model that included the creation of a Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), a truth commission, a unit to search for missing persons, and other measures to ensure accountability for those most responsible—both from the FARC and the state’s forces—for the gravest crimes, as well as reparations for nearly 10 million victims of the armed conflict. The goal was to strike a balance between harsh retributive justice—imprisonment—and sweeping, unconditional amnesties.

Uneven advance

Far from representing “peace with impunity,” as critics of the agreement claimed, this transitional justice system has drawn international acclaim for its comprehensive design, adherence to international law, and victim-centered approach. It is a unique example of a negotiation in which both the state and an insurgent group agree to submit themselves to a tribunal for atrocious crimes. But explaining this to the average Colombian has not been easy—especially when they see former FARC leaders, now under the Comunes party, sitting in Congress and taking part in politics while their judicial cases move forward at a slow pace. Only this year, the first rulings have been issued: one in a kidnapping case in which FARC leaders fully acknowledged their responsibility, and another addressing extrajudicial killings committed by members of the security forces.

Photo by Joaquin Sarmiento/AFP via Getty Images

The Peace Accord, however, was far more than a set of incentives designed to persuade the guerrillas to demobilize and disarm. It laid out an ambitious agenda to address the root causes of the conflict. Among its most significant components were strategies to develop long-neglected rural regions and to curb drug trafficking, which for decades had fueled the war. The effort sought to tackle deep-seated structural problems: rural exclusion, weak state presence, and the grip of illegal economies, particularly coca cultivation. Implementing these reforms demanded long-term political commitment—a condition still unmet.

Nearly a decade after its signing, progress has been made across various agendas, but advances have been uneven and slow. Two governments with opposite visions have come and gone: Iván Duque’s (2018–2022), with a pledge to reform the agreement, and Gustavo Petro’s (2022–2026), with a promise to fully implement it.

A narrowing window for peace

Soon after FARC laid down arms, Colombia’s relative calm gained during the peace negotiations unraveled. The national homicide rate plateaued at around 25–26 per 100,000 inhabitants—a level low by historical Colombian standards but still high relative to Latin America, the most violent region in the world. In contrast, rural areas hardest hit by the war experienced a severe increase in violence against communities and social leaders, as well as escalating attacks on former FARC combatants—at least 500 of whom have been killed to date.

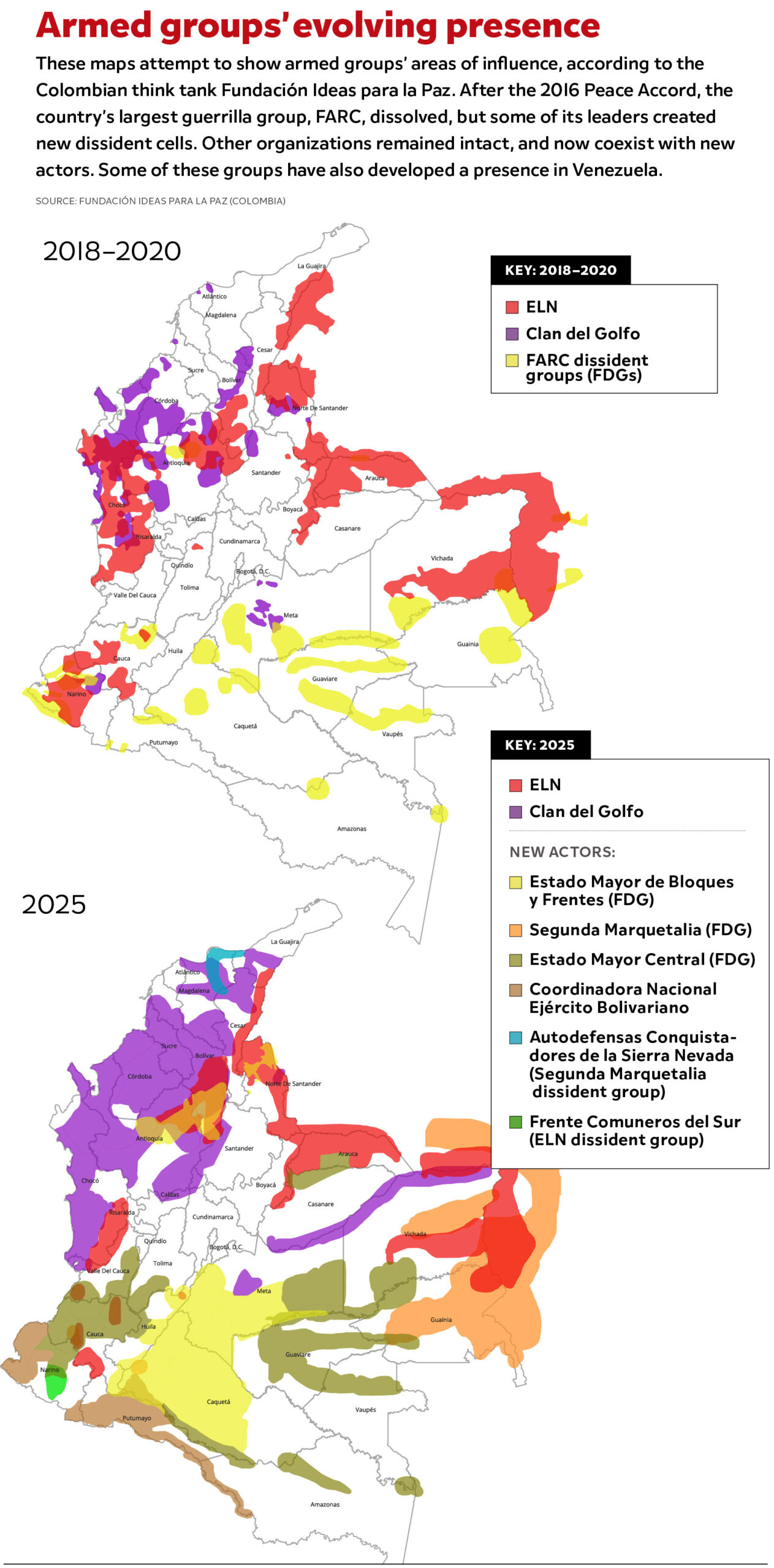

Much of this violence stemmed from the power vacuum left by the FARC. State institutions failed to take control of their former territories, creating opportunities for armed groups to expand their areas of influence and gain control over criminal economies, particularly narcotrafficking, illegal gold mining, deforestation, land grabbing, and migrant smuggling.

The most significant initial expansion came from the ELN, a guerrilla group from the 1960s that the Santos government had been negotiating with unsuccessfully. The Clan del Golfo also grew; this criminal group, now calling itself the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia (AGC), emerged as a dissident structure after the paramilitary demobilization achieved under President Uribe in the early 2000s, during which more than 30,000 fighters laid down their arms.

The picture was further complicated by various FARC dissident factions that emerged sporadically before and after the accord, eventually clustering into two blocs seeking to unify: the Estado Mayor Central and Segunda Marquetalia. Ultimately, however, both ended up fragmented.

Although the agreement succeeded in ending the historic armed conflict with the FARC, the landscape was already populated by actors—more interested in capturing territorial rents than seizing national power—who would become spoilers of peace. Neither the military offensives launched in certain regions at the end of the Santos administration, nor the hardline measures adopted under Duque’s terms, managed to contain the situation.

During the Havana negotiations, coca cultivation expanded exponentially, intensifying criticism of the process. With only 18 months left in his term and under adverse political conditions, Santos launched the voluntary crop substitution program agreed to with the FARC. However, the program relied on costly payments to nearly 100,000 families to uproot coca, creating perverse incentives and diverging from the Accord’s holistic territorial approach by avoiding necessary long-term structural reforms.

Despite opposing the agreement, President Duque acknowledged the state’s obligation to implement it, though without the political conviction needed to advance its various components. Duque prioritized one rural agenda item: the Development Programs with a Territorial Approach (PDET), intended to transform 16 regions identified as the most affected by war, illegal economies, structural poverty, and institutional weakness. His effort to deliver on the commitments made to hundreds of thousands of residents who helped develop these plans was notable. However, his approach remained disconnected from other components of the agreement and from his security policy.

Facing the coca issue, Duque opted for forced eradication, achieving record-breaking levels of eradicated crops while reluctantly maintaining Santos’s voluntary substitution program. At least 400,000 hectares of coca were destroyed during his administration, yet the net impact was negligible, as cultivation continued to rise. Communities saw a state willing to destroy their crops but unable to deliver on long-promised alternatives—deepening mistrust.

The limits of “Total Peace”

By the time Duque left office in 2022, public frustration was high. The COVID-19 pandemic and widespread social protests reflected deep grievances over inequality, unmet promises of inclusion, and the stagnant peace-building process. Gustavo Petro, a former M-19 guerrilla, capitalized on this sentiment with a progressive platform and a pledge to fulfill—and expand—the 2016 accord.

His signature initiative, “Total Peace,” sought to negotiate simultaneously with an array of armed actors, from the ELN to urban gangs. The goal was humanitarian relief, territorial reforms and, ultimately, national pacification. But the policy lacked clear strategies, legal frameworks, and operational discipline. Critics—including former President Santos—warned that opening so many talks at once risked diluting state capacity and slowing progress on implementing the original accord.

Their warnings proved prescient. Today, Total Peace has become a major failure. The main armed groups—ELN, FARC dissidents, and the Clan del Golfo—have strengthened under initially granted ceasefires. Their territorial expansion has been significant, and their ranks have grown by 85%. These groups have at least 25,000 members (up from 6,500 in 2017) and are constantly fighting to control territory, while the state’s presence and local legitimacy are in decline.

Meanwhile, implementation of the 2016 accord stalled. Petro has prioritized land reform—a central issue for him personally—and made real progress on land formalization and acquisition. But momentum behind the PDET, which had gained traction under Duque, slowed considerably. Coca policy shifted again: Forced eradication was halted, and a new voluntary substitution scheme was introduced. Cultivation has surpassed 240,000 hectares.

Amid a broader shift in U.S. foreign policy under President Donald Trump’s new term, the Petro government was decertified by the U.S. for what Washington described as weak performance in the fight against drugs. The move heightened tensions between Washington and Bogotá and strained a long-standing strategic partnership that had been central to Colombia’s security and to the implementation of the Peace Accord.

A paradox at the heart of peace

Across the regions hardest hit by violence, communities still voice a consistent message: The Peace Accord contains the right tools to transform their territories. What has been missing is sustained, coordinated implementation—insulated from political swings and backed by a robust state-building process.

Colombia thus faces a striking paradox. Most of society recognizes that the structural reforms outlined in the 2016 accord are still essential. But the process has become trapped in political disputes, shifting priorities and a security environment transformed by new criminal dynamics. The window of opportunity is narrowing, even as the need for long-term, patient implementation becomes more evident.

Hope, however, has not disappeared. In many rural areas, communities continue to participate in local planning, demand state presence, and insist on the fulfillment of promises made nearly a decade ago. Their persistence suggests that, while the peace process may be faltering, the aspiration for peace remains alive—and that Colombia still has a chance to correct course before it is too late.